Perspective on Appalachian Ohio: The Small-Town Mayor

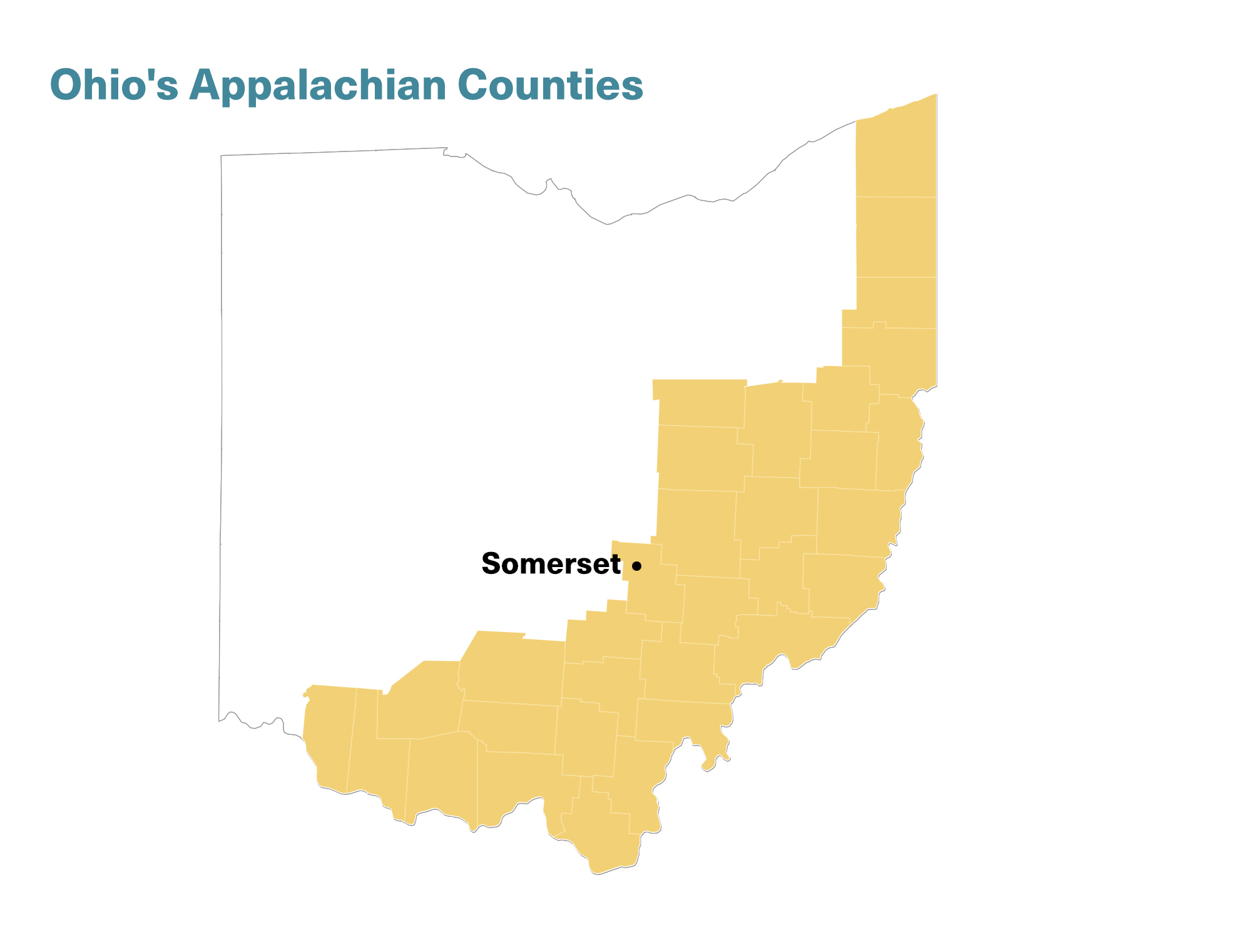

What can a town of 1,481 people in Appalachian coal country do in the face of long-term cyclical changes in global markets? Quite a lot, actually. Tom Johnson, mayor of Somerset, Ohio, explains.

Photo: Erin Clark

Tom Johnson grew up in Somerset, a community on the northern edge of Appalachian Ohio and an hour from the state’s largest city, Columbus. He left the region for a career in investment banking but returned after retiring early. He has been mayor since 2010 and also works on regional issues as executive in residence at Ohio University’s Rural Revitalization Partnership Initiative.

He explains how improved sidewalks, holiday parades, and Oktoberfest are all part of building the community up and preparing it for the economy of the future.

Q: Could you explain a little bit about your background and how you became the mayor of Somerset, Ohio?

Growing up, I knew I wanted to leave the area. I went to Rio de Janeiro as an exchange student at 16 years old. I majored in international studies at Ohio State. Eventually, I went into investment banking and worked in Los Angeles, London, Singapore, Miami, New York, and London again.

Then, in 2002, I retired at 45 years old and came back to the town I grew up in. Perhaps I was naïve to think I had enough money to retire, but my parents were getting older and I wanted to spend time with them in a way I hadn’t during my adult life.

The community was also a draw. I wanted to be involved in things like starting a farmers’ market to decompress from constant international travel. I got involved in a number of volunteer projects that grew until eight years ago I was elected mayor.

Q: What do you see as the opportunities and challenges for Somerset?

One of my goals as mayor is to be on the cutting edge of community-led economic development principles. We’ve joined Smart Growth America. We attend National Development Organization Association conferences. We reach out to create partnerships with other communities that are doing world-class development and try to bring more of it to this region.

But part of moving forward is understanding there are significant disparities across a broad spectrum of issues: educational attainment, population health, poverty, and economic development. There’s the legacy of extractive industries, particularly coal. Buckingham Coal Company is still a key employer in Perry County.

We can’t fix the disparities if we don’t understand them. We need to own them without letting them define us. We want to test approaches to addressing the disparities, do evidence-based evaluations to determine if they’re successful, and replicate those that are around the region.

Q: You mentioned educational attainment as a disparity. Could you explain what that means for the area?

If you look at my county, 17% of the adult population doesn’t have a high school diploma. Only 8% have a bachelor’s degree or higher. When you have that high a percentage of people not having a high school diploma and so few having college degrees, most kids would be first-generation college students. Combined with a norm of not leaving the community, of staying close to family, and there are cultural barriers to education in the Appalachian region.

We got money in a state capital bill to create a learning center and technology hub in Somerset. Then Jennifer Simon at Ohio University got $2 million from the Appalachian Regional Commission for a network of innovation centers in Appalachian Ohio. Somerset is part of that network. We’ll have a maker space that will offer a career pathways curriculum that will let high school students earn college credits for facilitated online learning. Eventually, we want to let people earn degrees and certifications without ever leaving the town. That could have a major impact on educational attainment.

Wouldn’t that be great if portals to higher education and maker spaces that can be catalysts to innovation and entrepreneurship popped up like mushrooms all over the region?

Q: What’s the economic future for the area?

I was part of a group the Appalachian Regional Commission pulled together to brainstorm strategies for asset-based development for rural communities. Among the ideas we looked at were advanced manufacturing, outdoor recreation, tourism, and medical services.

Healthcare is a potential economic driver in rural Appalachia and at the same time a way to address significant disparities in access to healthcare. Perry County has 36,000 residents and eight primary care physicians.

After four years of work, we’ve got a $10 million medical center coming to Somerset. It will mean 67 new jobs and around a $5 million annual payroll.

Q: How much does the status of the Affordable Care Act matter to the project?

It’s critical. It was a courageous decision by the hospital system, Genesis Healthcare, to expand with that unknown. When the Affordable Care Act came in and Medicaid was expanded, it changed things for low-income, rural communities. A third of the population in our county is on Medicaid. More people with health coverage represent a revenue stream that can support additional healthcare businesses.

We aim to leverage the hospital’s investment to create federally-qualified clinics staffed with nurse practitioners and community health workers who can help a population that’s not used to having primary care learn to navigate the system. We will launch population health and wellness initiatives which over time will help with health disparities.

Then there’s the 67 new jobs. We’re not going to attract medical professionals from urban areas to rural Appalachia. It’s culturally different, and it’s not rewarding financially. Ohio University has been successful relative to other universities in educating rural doctors. That needs to expand. Four school districts in the county have agreed to fund tuition and transportation for students who want to fast track into those new jobs.

Q: The hospital will be great for Perry County, but I can imagine surrounding counties would have liked it, too. How do you keep struggling communities from zero-sum competition?

The traditional approach to economic development can lead to that. It’s risky in my view because communities become dependent upon an outside employer. With asset-based development you build on the local capacities.

The Appalachian Mountains are what define the region. The star of the show in Appalachian Ohio is the environment and outdoor recreation opportunities. It’s one of the most biologically diverse regions of the country. We’re working on branding the region—Pennsylvania has the Pennsylvania Wilds, Virginia has the Crooked Road, West Virginia has Wild and Wonderful— we’re working to develop an Appalachian Winding Road experience.

Because it’s asset-based, we’re not competing. We’re improving our communities and the region as a whole. In Southeastern Ohio, we have the Hocking Hills. They get more visitors a year than Yellowstone National Park. Old Man’s Cave is an amazing natural asset. One of the top Native American archaeological sites in the state is 6 miles from Somerset. We’re 11 miles from Buckeye Lake.

One rural town of 1,500 people is not going to keep visitors here for three days, but we can be a base camp for the larger region. We can tap into the millions of people who live in and around Columbus. But right now, that’s theoretical. Somerset doesn’t have lodging. There’s an effort to renovate a historic structure and open it as a boutique hotel. Others are considering opening up bed and breakfasts in town.

Because we haven’t seen development, Somerset and many other towns in the area still have our unique historic downtowns. Rural Appalachian communities tend to have low penetration of outside businesses. We don’t have a Walmart. Somerset has a walkable core with 50 businesses. We still have a pharmacy, a hardware store, local restaurants, barber shops, doctor, dentist, etc.

Q: What’s involved in making the area a tourist destination?

We’ve been very successful in getting funding for the community, county, and region because we search out what’s working, search out best practices, and match it to what the state and federal governments are supporting. The director of the Appalachian Regional Commission once described me as a master at R&D—rip off and duplicate. It’s true. There’s no need to recreate the wheel. I look for successful, creative approaches and reshape them to make them relevant to our community.

I’ve been working with other redevelopment-ready communities that have leadership that’s interested in this type of economic development and building a creative economy. We’ve been sharing our successes and introducing them to creative partners, urban planners, architects, and engineers to help them pull together projects that they can get funded and do in their communities.

Four years ago, I was appointed to represent the Appalachian Region on the Governor’s Arts and Culture Capital Bill Committee. That committee was tasked with coming up with about $30 million in arts and culture projects, funding recommendations from across the state. We agreed to direct funding to each region based more closely to population.

Appalachian Ohio received $3 million; we hadn’t received anything like that in years. Our communities didn’t have projects ready to submit because they hadn’t had access to funding in the past. We were able to get 18 projects funded throughout the region. One of those was Stuart’s Opera House. They received half a million dollars which they leveraged into a $4 million renovation with strong local, private funding. That’s now a resource for Nelsonville and a draw for tourists.

Q: How common is it to have support for change?

Some communities are not redevelopment ready. Some communities don’t have leadership in place that are open to new ideas, that are willing to change. Change is not easy either.

There’s a lack of leadership and capacity in both public and private sector. If you look at, for example, the number of elected officials in an Appalachian county with a small population, the ratio of the size of the community to how many are needed to serve is like 70:1 versus larger metro areas that would be several thousand to one. So, we don’t have the depth of talent pool we’d like for local government.

Traditionally in Appalachia, because we were isolated, we’ve been leery of outsiders and don’t defer to outside expertise. The guy at the coffee shop is going to have an opinion on affairs of the day. Each person’s view is equal to everyone else’s. It’s very egalitarian.

Today, we can Google the answer to a question. We can hire a top architect anywhere to design something. But that’s not the tradition. That’s not the Appalachian way. Some people are uncomfortable with different approaches. They resent any change and push back.

One of my first grants was $40,000 for sidewalk repairs. Some people were upset because everyone is supposed to take care of the sidewalks in front of their own house. The sidewalks around the main square were in really bad shape. They hadn’t been maintained in 50 years, probably.

Then I got a grant to create a 35-acre nature preserve. The guys at the coffee shop wanted to know, “Who’s going to maintain it?” Well, it’s a nature preserve; it maintains itself.

We got water and sewer grants. People said it would tear up the streets. Well, fixing water and sewer lines does mean tearing up the streets. Nobody likes that. But the work was long overdue.

It wasn’t until the streets were repaved and we got a million-dollar streetscape grant that let us put in herringbone brick sidewalks and antique-looking streetlights, then people were amazed.

We’ve scoped out a $12 million downtown redevelopment project. I talk to people about that and they say, “Do you think we could ever do that?” I say, “Well, who would have ever thought we’d get a $10 million medical center?”

Q: What creates the willingness to change?

A spark plug for these kinds of initiatives, that’s a big part of it, because you need to have community pride and appreciation in order to maintain the momentum for the next step. You also have to go top-down and bottom-up. We have really strong local community groups. We started the farmers’ market and a community kitchen. We’ve got a Christmas parade, an art walk, Oktoberfest, and a Fourth of July parade. We have such a beautiful town square that, when we have events, it’s such a source of pride.

Q: You’ve described a lot of positive steps. How is the opiate epidemic impacting the area?

The opiate issue is really difficult. To give you a sense of the scale and scope of the opiate epidemic, employers can’t find people that can pass a drug test. It’s creating labor shortages in the region.

The county is going broke on jail costs. When we blow our budget on jails, it results in other areas seeing salary and hiring freezes and the inability to invest in the many other areas that need it. Lots of mayors in the Southeastern Ohio Mayors’ Partnership described similar situations. I talked to a state representative who said half the counties in his district aren’t arresting people because they can’t afford it. How do you think that would go over in other places?

The Attorney General has launched a pilot project to help children in families that have been affected by addiction. Three counties in Appalachian Ohio opted out of the program because, despite state-level funding in these rural areas, there simply aren’t people trained and available to provide treatment.

People who do manage to get treatment and are in recovery have difficulty getting normalcy back into their lives because they’re oftentimes felons and unemployable. Again, this is an issue we in the region have to get our heads around and advocate for solutions.

I talked to the CEO of a company that provides behavioral health treatment in the Appalachian region. In the past, treatment included medication and talk counseling. Now, they’re integrating more and more things that can give people a purpose to their lives while they’re in recovery. It could be an activity—gardening—but it can be more. Imagine if we build career pathways into treatment. Imagine if we did that in the jails and prisons, too. Creating a trained workforce and providing people who are struggling with an opportunity for prosperity, wouldn’t that solve more than one problem at the same time?

In Perry County, we’re looking into opening a residential medically-assisted treatment facility. Instead of paying to keep people in jail, which costs the local towns and counties, sentencing them to medically-assisted residential treatment could be a local option for treatment that Medicaid will pay for.

Q: Where do you see the region going in the future?

The Appalachian Regional Commission maps show economically distressed counties in red. There are four levels: distressed, at-risk, transitioning, and attainment. Perry County moved from at-risk to transitional in January. I’m really proud of the fact. I want the community to be proud of that fact, and I want to see Perry County move to attainment within four years.

I think we could set a goal of getting all the red out of Ohio within four years. Those sorts of targets let you know what to aim for. It’s why it’s important to analyze the disparities so that you’re clear on what you don’t have.

Many towns, many local officials, don’t know what they don’t have because they’ve never seen anything else. I’ve lived all over the world; I know we live in a beautiful place. But I also know we have counties that have been treated like throw-away counties. I’m not willing to say there are any throw-away communities. I vote for hope. I believe we have the competency in the region to collectively address these challenges. I know it’s not all despair.

Bill Dingus has built up $60 million in equity in the Lawrence County economic development entity. That’s a big success story. Perry County has zero dollars of equity in ours. Our bonding capacity is zero. That’s an example of the disparity that exists. We didn’t have an economic development agency. I worked with the county to form one, and we have a target to shoot for.

Muskingum County, next to us, has $25 million in endowment in the community foundation they started 10 years ago. Perry County didn’t have a community foundation; now, we started one and we’ve got our first million.

There was $50 million available for coal-impacted communities last year through the Appalachian Regional Commission. There was $30 million available for coal-impacted communities from the Economic Development Administration. We’ve never had those kinds of resources available before. If we can get that level of investment behind what we’re trying to do here in Appalachian Ohio, there’s hope that we can we actually transition to prosperity.

I went to China in 1979 when I was a student. Shanghai had no skyscrapers. I remember walking down the Bund—the waterfront—past beautiful old buildings. There was a sea of people wearing Mao suits riding bicycles and just a few trucks going down the center lane. I returned to China while working in banking and saw the amazing skyscrapers and such prosperity. They were worse off than we are. If China can do it, Appalachian Ohio can do it.

Interview conducted and edited by Ted O’Callahan.