Can Appalachian Ohio Build a New Economy?

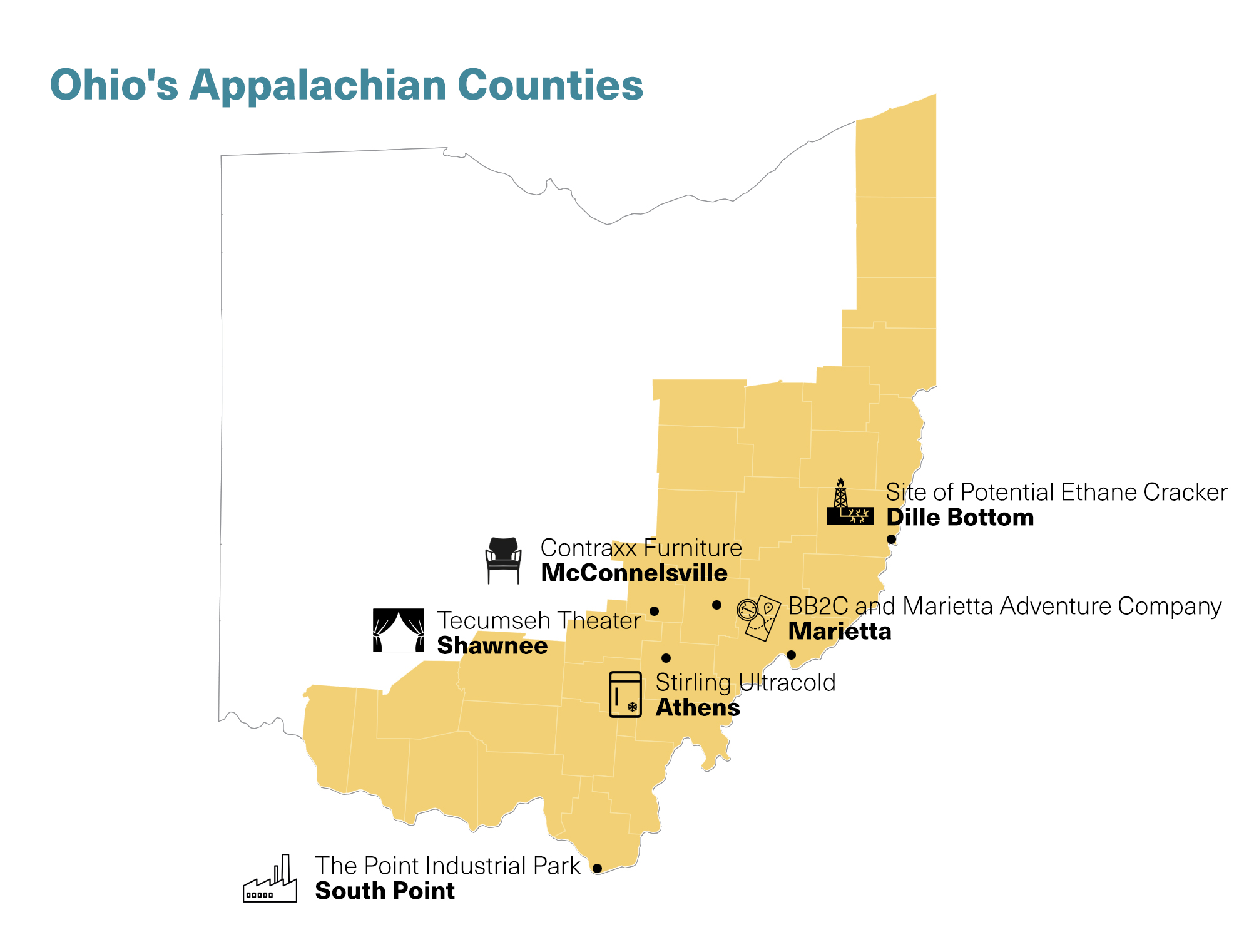

Poverty remains stubbornly rooted across Appalachia. The 32 Ohio counties spread over the Appalachian foothills suffer in comparison with their counterparts in the rest of the state by nearly every economic measure. But they’re also filled with entrepreneurs, philanthropists, and citizens seeking to build a brighter future.

Businesses in downtown McConelsville, Ohio. Photo: Erin Clark.

The outlines of Appalachian Ohio are visible from space. The rumple of hills, hollows, and rivers shows clearly in satellite imagery, in sharp contrast with the icecap-flattened terrain, now cut into agricultural and city grids, that makes up the rest of the state. The heavily forested Appalachian landscape is beautiful but not conducive to large-scale economic activity or even to a single large city. It has 40% of the state’s landmass but only 17% of the population. In southeast Ohio, few towns top 25,000 residents, while the other corners of the state have urban anchors.

“Appalachia” has become a byword in American politics for the lingering challenges of rural poverty in the world’s dominant economy, conjuring images of abandoned factories decaying to rust, shuttered coal-fired power plants, and depleted mines. A closer look shows, yes, stubborn barriers to economic growth, but also resilience, a vibrant culture, and diverse efforts to spark forward-looking economic development that offer reason for hope.

***

Ohio’s hill country developed around natural resource extraction, like much of Appalachia. Again and again, outside money rushed in to exploit a boom and pulled out with the bust. Serial frenzies of economic activity didn’t bring steady incremental improvements in infrastructure, economic diversification, or social capacity.

For residents of this area, one response has been to leave. In the early 20th century, iron smelting created such a demand for charcoal that entire forests were fed into furnaces. The denuded hills eroded, resulting in untillable land; 40% of the population left between 1900 and 1930. Then, after World War II, outmigration sent so many people to Midwestern factory cities that Route 23, which leads from Appalachia to Detroit, was called the Hillbilly Highway.

Shawnee, Ohio, a coal town clinging to the side of a hill, can be seen as a tableau of both the weight of history and the resolve of people in Appalachia to shape a new future. Shawnee was so bustling during a late 19th- and early 20th-century boom that it had two competing opera houses. It is now down to a population of 643 and its Main Street is pocked with abandoned storefronts. But there are people fighting fiercely for Shawnee, and they are oh-so-slowly restoring one opera house—replacing rotted trusses, refurbishing the façade, and tuckpointing brickwork—while keeping a protective eye on the second.

According to the Appalachian Regional Commission, the population in Appalachian Ohio shrank by 1.9% from 2010 to 2016, as the population of the rest of the state grew by 1.2% and the population of the United States by 4.5%. Median household income in Appalachian Ohio was $44,351. For the rest of the state it was $52,282, and nationally it was $55,322. During the same period, the poverty rate was 17.6% in Appalachian Ohio, 14.9% in the rest of the state, and 15.1% nationally. The trend of lagging state and national figures continues for health, safety, disability, and access to healthcare. The percentage of adults with at least a high school degree is close to national rates, but the percentage with college degrees lags; in Appalachian Ohio, 17.1% have a bachelor’s degree or more while in the rest of the state that number is 28.7% and nationally it’s 30.3%.

In a way, the answer to the region’s challenges is simple: economic development. But what does economic development mean in practice? How does it create jobs that put money in peoples’ pockets?

Economic development is people making choices, working day by day to make things better. It’s a nub of land on the Ohio River where an industrial park has emerged from a remediated Superfund site. It’s a New York-style loft in a tiny Appalachian town where a half-dozen creative-class professionals run a custom furniture company. It’s a high-growth, high-tech startup in a nondescript building in the rural outskirts of a university town.

Attraction

Like wallpaper, economic development done right makes things nicer—but most people would be hard pressed to say how. And if it’s done wrong, nothing is quite right. There are three approaches: attracting outside business, retaining and expanding existing companies, and creating new activity through grassroots entrepreneurship. There’s certainly no rule that these approaches are mutually exclusive; in fact, most of those doing economic development in Appalachian Ohio underscore the importance of engaging in all three as a means of diversifying the regional economy.

Beyond that, economic efficiency is rarely the sole factor in regional economic development. Values, culture, and politics inevitably get rolled into the mix. Clear evidence for what will work best is rare. The methodical testing of development projects through randomized controlled trials, which is increasingly being used in emerging economies, is not widespread in the U.S. Even when there is economic research to offer guidance, the gap between theory and practice is quite large, leaving leaders reliant on experience and rough examples of what has worked in the past or in other places.

A proposed $5 billion to $10 billion ethane cracker on the Ohio River is attraction writ large. It would turn natural gas from the Marcellus and Utica shale deposits into ethylene, a building block that is used in plastics and many other petrochemical products. PTT Global Chemical, Thailand’s largest petrochemical company, is doing preliminary site work on a 186-acre parcel in Belmont County. If it goes ahead, the plant would create an estimated 300-500 direct jobs and many more through the ripple of affiliated businesses.

John Molinaro, president and CEO of the Appalachian Partnership, a nonprofit that fosters regional development, says the ethane cracker is an example of the value-chain approach to economic development he wants to see in the region—using local raw materials to make higher-value, exportable products. “Eastern Ohio is very rich in the feed stock to the plastics industry,” he says. “It makes sense to capture more of the downstream use of the natural resource being produced in our region.” Unlike consumer-facing development—say, a new Walmart—an ethane cracker isn’t “trying to attract dollars already circulating in the local economy—their activity is going to add in increments to the economy.” But similar cracker projects have fizzled after years of work and hope. That’s a critical downside with huge projects—it is a home run or a whiff.

Losing out on big projects is difficult on communities, especially after decades of mine and factory closings. “The big events are what people remember,” says Bret Allphin, the development director for the Buckeye Hills-Hocking Valley Regional Development District. “The knee-jerk reaction is, ‘How do we get another aluminum manufacturer to employ 2,000 people?’ but the data show a slow decline.” So, in addition to periodically swinging for the fences, recovery is likely to require numerous smaller-scale efforts, too.

But who does the work? “Rural areas have a problem of scale,” says Allphin. “Being a mayor or county commissioner, in many places, is a part-time job.” He knows one mayor who also drives a school bus. Another who is a mayor-farmer. “We assume ‘they’ are going to do it. Well, who is ‘they’? We are.” Small towns and counties have fewer people, a smaller tax base, and a higher cost per person for infrastructure.

Even the smallest communities require a minimum threshold of economic infrastructure—capital sources, diversified business activity, relevant talent, a training and education pipeline, healthcare, and basic government services. In a struggling area, can a handful of mostly part-time officials devote attention and funding to each thing? Does this year’s budget put money toward getting Narcan—a medication that can reverse opioid overdoses—in every sheriff’s department vehicle or an economic development project that may or may not have a clear and immediate payoff?

One approach is to pool resources. Allphin works for a regional council that provides eight counties, with a total population of 260,000, a means to access dedicated economic development expertise. The Lawrence Economic Development Corporation (LEDC), a nonprofit corporation, does similar work in Lawrence County. The county’s smaller-scale variation of the attraction model can be seen in South Point, Ohio, where what was a Superfund site has been remediated into a 504-acre industrial park with 17 firms representing more than 700 jobs.

The industrial park isn’t exactly beautiful, but there is an appeal to its clean lines and new roads. The heavy machinery feels like a grown-up version of an Erector set—for example, a 50,000-ton straddle crane that moves shipping containers onto trucks or trains. Eight miles of train tracks loop through the property, meaning that rail cars can enter and exit without being turned, a convenience that can be measured in time and dollars. A port on the Ohio River completes the intermodal suite of capabilities for receiving raw materials and shipping out finished products.

The site has an inholding that was not acquired or redeveloped. The contrast between the blighted remnant buildings on the inholding and the trim new utilitarian structures surrounding it are a stark illustration of the difference between American carnage and great again.

Dr. Bill Dingus is a long-time regional political actor and power broker who worked for 25 years as the founding dean of Ohio University’s southern campus in Ironton. Dingus explains that when he took over LEDC 15 years ago, the organization had around $1.5 million in assets; today it has over $65 million. The equity is opportunity; it’s strength and capability. LEDC can provide a promising tenant help with financing. If a company would like a turnkey facility, LEDC can do that.

When FedEx was interested in locating a facility in the park, Dingus worked with the company through round after round of vetting and inspections. “I knew FedEx’s diligence would serve as reassurance to firms that would have a hard time doing it themselves,” he says.

“In rural areas, economic development isn’t a process, it’s a person,” he says. Dingus is also the executive director of the Greater Lawrence County Area Chamber of Commerce. In each role, he adds, he empowers his staff and cultivates loyalty, but the efficiency of consolidated decision-making power is necessary. He’s aware it makes some people uncomfortable, but expedience gets results in a place that desperately needs them.

There is a scrappiness to this work. It’s horse trading to access $300,000 of state matching funds for railroad crossing signals. It’s tapping federal stimulus and Ohio Department of Transportation funding to build the port infrastructure. It’s renting out that river frontage for barge parking during periods when the cost of diesel slows river traffic. “You do what you need to do,” Dingus says. “Each case is unique.” But everything moves LEDC toward more strength. The track record, the balance sheet, the infrastructure and expanded organizational capacity all put LEDC in position to grab bigger opportunities.

Tom Johnson wishes his county had a similar base to work from. “Perry County has zero dollars in bond capacity,” he says. Johnson retired in his 40s from a globe-trotting career with Standard Chartered Bank and returned home to Ohio to be near family. Successful volunteer efforts to tap grants and public funds for a revitalization of Somerset’s historic downtown led him to run for mayor, a position he has held since 2010.

In a town and county that’s strapped, economic and community development bleed together. “You need to go top down and bottom up simultaneously,” he says. Grassroots projects like a farmer’s market, a Christmas parade, repaving sidewalks, and repainting downtown buildings have a real impact. The energy and engagement of the community is a form of momentum. So is the $10 million hospital that’s coming after four years of recruiting by Johnson and other leaders. The county currently has eight primary care doctors for 36,000 residents. The new hospital will bring 67 jobs and $5 million in annual payroll. It could anchor additional development, which might eventually let Johnson make progress on longer-term, less visible things like county bond capacity or the indirect efforts required to develop a culture and infrastructure of entrepreneurship.

While those working to help Appalachian Ohio are pulling in the same direction, there are differences. Dingus says, “Attraction is 1,000 times more valuable than entrepreneurship.” The value of a new plant or facility is easily measured, while dollars directed to fostering entrepreneurship can disappear. “We in Appalachia have been bad about eating the bait and not catching the fish,” he says. Dingus isn’t looking to repeat the cycle of external capital coming and going. “We need to hold the private sector accountable for ensuring communities benefit from economic activity.” And that’s more likely to happen if the region develops more capacity for self-advocacy. “We act as if Appalachia is a unit. It’s not. There’s too little collective effort and political power.”

Appalachian Ohio is nearly three times the size of Connecticut. There are significant geographic and historical splits within the region. Ohio’s three Cs—Columbus, Cleveland, and Cincinnati—each exerts gravitational pull on the closest Appalachian counties. This dissipates the political influence the region might otherwise have. And the strongest economic engines vary within the 32 Appalachian counties. Heavy industry, advanced manufacturing, forestry, agriculture, natural gas fracking, and even the little remaining coal mining all have different geographies.

Retention and Expansion

A three-hour drive north from South Point’s industrial park is McConnelsville. The town of 1,784 people is set on the north shore of the Muskingum River and surrounded by hills that are either forest or farmland. It has three stoplights and a downtown of beautiful, if worn, brick buildings. It’s the county seat for Morgan County, which has been held up as a model for developing and implementing plans for a long-term economic recovery. An Appalachian Regional Commission-sponsored report notes, “Their willingness to break with the past and embrace youth and learning as the focus of their efforts is remarkable and should serve as a model for other distressed communities.”

That past is still just a few miles away. Sixty thousand acres of reclaimed strip mine have been turned into recreation land by American Electric Power. The bucket from Big Muskie, a machine that could move 39 million pounds of earth per hour, remains as a memorial to the area’s industrial heritage.

“In the ’80s and ’90s, anyone you talked to thought the end of the world was coming,” Mike Workman says. Morgan County had lost 1,000 coal mining jobs; another 800 jobs disappeared when a window manufacturer closed. Then, in 1995, the furniture factory where Workman was employed closed—a bank bought the company, he recalls, but just wanted its stock exchange seat. Another 160 people were laid off. Nearly 2,000 jobs gone from a county of 14,000. Even so, Workman says, “I never thought the community wouldn’t make it.” That isn’t the same as things being easy.

Waiting out busts is a common strategy in many undiversified economies. Morgan County is still sitting on unmined coal. Who wouldn’t hope for another boom? But, Workman says, “don’t wait. Hope is not a strategy.”

He bought enough equipment at auction to begin making stools, and that’s all his company did for five years. He had three employees. “Life was good. Life was simple,” he says. When a customer asked, insistently, the company began making tables, then chairs, then cabinets. That customer was Chuck Williams, the founder of Williams-Sonoma.

Much of the furniture making in the U.S. was lost to global competitors, in Workman’s view, because domestic manufacturers competed on price. Instead, he saw a business opportunity in “quality, design, history, and value.” He saw an opportunity to work with hotels, resorts, restaurants, and other commercial clients to create custom furniture.

Contraxx Furniture describes its model as an at-will cooperative—it’s a variation on the Mondragon Corporation, a worker-owned cooperative that is one of the largest businesses in Basque Spain. The team in McConnelsville does the external-facing work: design, marketing, and sales. They bring the orders to a self-organized collection of 250 Amish and Mennonite craftsmen in southeast Ohio, whose “factories” are family businesses in barns or other similarly small-scale sites. They are coordinated by a hub that brings the elements together for assembly and finishing. “There’s no inventory, no management layers, no factory overhead. It’s distributed manufacturing done through a network of independent, at-will artisans,” Workman explains. In his view, it works because it emerges from the place. “It’s a cultural model as much as an economic model.”

Contraxx Furniture’s office is in a loft space of wood, iron, brick, and glass. It could well be in Soho. And many of the furniture design company’s clients are in New York, Los Angeles, or Miami. But the loft’s massive windows face McConnelsville’s Main Street.

There’s no reason world-class work can’t happen in Appalachian Ohio. That’s the implicit argument in so much of the economic development in the region. “Appalachia has never marketed itself the way cities do,” Workman says. In fact, much of the region’s “marketing” has come in the form of stories about the War on Poverty going back to Lyndon Johnson and even earlier. If it’s possible, many Appalachians are as tired of being seen as poor as they are of being poor.

Perversely, even as conditions have improved dramatically throughout Appalachia in the last 50-plus years (the poverty rate in Appalachia has fallen from 31% in 1960 to 17% and the number of high-poverty counties has fallen from 295 to 84), the experience of difference may have been heightened. Access to television and then the internet made other parts of the country the norm. Bill Dingus says, “Growing up, I wasn’t poor because everyone was.”

There was also a shift in society, according to Jack Frech, who led Athens County’s welfare agency for 33 years before retiring in 2014. He saw the War on Poverty become a war on the poor. “The message that it is shameful to be poor has gotten through to those who are poor.”

Charlie Hudson, a member of the city council in Wellston, says that making progress requires rebuilding pride, step by step, through thoughtful, engaged efforts from the private, public, and nonprofit sectors, simultaneously. The message, he adds, must be consistent: “We can be better. We can do better.”

Workman, who grew up in West Virginia and southeast Ohio, says, “I’ve always lived in a poor part of the country but never accepted I was going to be poor.” He estimates he’s traveled more than 2 million miles in his lifetime and is at ease in any global city, but he wanted home to be in a small community. That has been McConnelsville since 1971. While he will never be a native, he has been around long enough to become one of the leaders helping the county in “seeking resurrection.”

One part of changing the perception of Appalachia is pointing out successes. Workman notes the designer who renovated Contraxx’s building worked for years in New York before returning home to Zanesville, Ohio, to open her own firm. The high-end construction was done by locals, too. “Whatever we dream up, we can find someone to make it,” he says.

“You create your own prison when you think, ‘I can’t do this because I’m here,’” Workman says. “Nobody anywhere has an exclusive claim on execution. You have to figure out what your advantages are. You have to create businesses. You go to local strengths and find world-class products and services that can be exported. If you aren’t exporting your product, you’re just running the money through the washing machine of the local economy.”

McConnelsville’s “retain and expand” development model got an important boost when Miba, an Austrian manufacturer of drivetrain bearings that already had one facility in town, expanded, bringing a new sintering facility to McConnelsville because of the competitive costs of doing business and the willing workforce.

That was 2013. Today Miba employs 600 people. And because the new facility is cutting edge, it’s a training destination. Executive housing is a challenge in much of the region. Aware of the need, and heavily involved in recruiting the Miba expansion, Workman created six executive apartments in the same building as the Contraxx offices. Miba recently re-upped its lease on all of them for another five years.

How is McConnelsville doing? “Walk the streets and count the smiles. That’s how you know whether you’re doing the right thing,” Workman says. There’s a sense of momentum, but that doesn’t mean all the problems are solved. “There’s no solving. There are steps,” he says. “Economic development doesn’t happen overnight, and it doesn’t happen just once.”

So, the next step? “We are leaking our human capital at an alarming rate,” Workman says. “College students leave and only return for visits to the family.” He’s ready to try inventive options. “We can forgive student loans for those who return to the community. We could offer low- or no-interest loans to start businesses,” Workman says. “It’s all synergistic. It’s not a zero-sum game.”

Entrepreneurship

Stirling Ultracold launched its core product, a highly efficient freezer for biological samples, in 2013. The company used a technology—the Stirling engine—that has tantalized tinkerers for 200 years because its potential for efficiency, compared to internal-combustion engines, seems almost alchemical. Stirling Ultracold found success in a narrow application of the technology that, while not world-changing, significantly improves an existing product. The company, headquartered in Athens, Ohio, has 100-plus employees.

As is often the case with an innovation, Stirling Ultracold’s rapid growth comes after years of work. William Beale, an engineering professor at Ohio University, invented the free-piston Stirling engine in 1964. He created Sunpower Inc. to continue research and development on a range of applications for the technology, and the company remains a significant employer of technicians and engineers in Athens today. Neill Lane led Sunpower for nine years before moving to Stirling Ultracold, where he is president and CEO, to pursue the targeted application of the free-piston Stirling engine in ultra-low temperature storage freezers.

Athens has become something a nexus for applications of the Stirling engine. Another local company, UltimateAir, uses Stirling technology to make a whole-house ventilation system. Stirling Ultracold has hit 75% year-over-year growth and expects to grow three-fold in the next three years. Biotech and pharma companies drive the $600-700 million-dollar market for -80°C freezers that protect lab samples. “We’re aiming to dominate the sector,” says Lane.

“Creating manufacturing jobs in Appalachian Ohio was explicitly a goal,” Lane says. “But, it’s not just that we are creating jobs; we’re doing world-class manufacturing.” He believes that approach is what will let both the company and the region succeed. “This kind of work comes with a set of cultures, values, skills, and norms.” Over time, those expectations, those capabilities, can shape a place and its workforce. “What gives people job security is being world class.”

Getting any startup to the point where it can prove itself through execution is difficult. “We’ve really benefitted from a microclimate the state of Ohio has worked really hard to create,” Lane says. Many key components of that microclimate are based just miles away at Ohio University.

Jen Simon, the executive director of regional innovation at Ohio University, says that the university makes sense as a home base for work that requires patience and a good deal of teaching. “I worked in economic development for years,” she says. “Nobody wanted to talk about entrepreneurship because it doesn’t fit within an election cycle. It doesn’t help local politicians get re-elected. They want the big win you get when you attract a big company.” But Simon believes the long-term effort to foster entrepreneurship will pay off: “If you can help someone that has roots in your community grow, they’re more likely to stay around.” It requires building capacity and showing enough results that others are inspired to emulate the successes. “The work is to create a new way of thinking.”

TechGROWTH Ohio, based on the Ohio University campus, is a hub for capacity building in technology entrepreneurship. John Glazer, its director, says the organization uses an intensive, hands-on approach because many potential entrepreneurs have viable ideas but no experience with taking a product to market or creating a company. “Instead of a quick no, we go for a slow yes to find gems.”

Ecolibrium, an Inc. 500 company based in Athens, manufactures racking systems that make solar panel installation faster and cheaper. Brian Wildes, the company’s founder, was a materials engineer who wasn’t happy with the existing options for racking systems. TechGROWTH Ohio and the university’s innovation center supported final development, validation, and launch of its product.

TechGROWTH and the other university-affiliated operational-assistance programs have worked with more than 2,000 entrepreneurs since 2007. In that period, client companies have created 661 jobs with an average annual salary of $55,567 while generating $450 million in economic activity.

Today, the entrepreneurial ecosystem around Ohio University is one of the most robust in rural America. The school has received national and international awards, including “Outstanding Emerging Entrepreneurship Program” and “Top University Business Incubator in North America.”

One catalyst was David Wilhelm. His father was a professor at Ohio University and he got his undergraduate degree at the school before leaving to launch a career that has spanned politics, finance, and energy. He headed the Democratic National Committee and managed political campaigns for Bill Clinton, Joe Biden, and others. And he has worked to spark entrepreneurship in Appalachian Ohio.

“Something had to get the ball rolling,” Wilhelm says. In the late 1990s, he led the creation of Adena Ventures, a $25 million Appalachian-focused venture fund. “Adena was a way to jumpstart growth companies in an off-the-beaten-path part of the country.” He wasn’t just a fund manager, he notes. “While my total investment was not as great as the institutional investors, as a share of my total wealth, it was much higher,” he says. “In fact, my wife and I took out a second mortgage on our house to support the development of Adena, which was a great personal financial risk at the time.” Like many other investments of that era, the fund’s returns were hurt by the dotcom crash and the recession of the early 2000s, but Wilhelm has no regrets. “While we didn’t get the returns, we did help spur the ecosystem that exists today.”

Wilhelm kept working. He helped build support for Ohio Third Frontier, the state’s entrepreneurship-focused economic development program. Wilhelm has also helped develop other programs at the university, and, according to Mike Workman, suggested Mondragon as a model for Contraxx Furniture.

To Wilhelm, and those who created the angel and venture funds that followed, entrepreneurship makes sense for Appalachian Ohio, where the problem-solving, we’ll-figure-it-out qualities necessary for rural life overlap with a startup mentality. It’s a place that does determined resilience really well.

Simon notes with satisfaction that entrepreneurship education is spreading beyond the university: “In the middle of Appalachia, a school district said, enough is enough—we want our kids to understand entrepreneurship.” Building Bridges to Careers (BB2C) developed quickly from a volunteer-built job shadowing program for students in Marietta into a nonprofit that offers a range of programs and services to most of the county’s school systems. “We are incubating ourselves,” says Tasha Werry, BB2C’s director.

“Kids have extremely narrow views of what careers exist,” Werry explains. Providing students with experiential ways to understand their options—job shadowing, internships, and other forums that allow young people to meet people in a range of professions—requires networks and partnerships. As students, parents, teachers, and business owners interact over time, relationships form. Students understand their options; businesses get to know their future workforce. Critically, seeing things differently and recognizing the changes that are underway lets young people understand that pursuing career opportunities and staying near home and family are not mutually exclusive.

That’s in part because of the example of young leaders and entrepreneurs in the preceding generation. Hallie Taylor grew up in Marietta before leaving to travel. She worked in New York for a number of years, then returned home for what she thought was a visit while she figured out which outdoorsy town in the West would be her next stop. Working up a wish list for a place to live, Taylor realized Marietta checked off a lot of the boxes. She was enjoying the recreational opportunities and the potential to be engaged in the community, so she decided to stay.

Taylor connected with Ryan Smith, another local who loves the outdoors and had returned after a stint in California. “Marietta is a great little town that I never saw clearly until I moved away for a little while,” Smith says. When he returned, “I saw a blank canvas of potential and felt like I could have an impact.” He launched the Rivers, Trails, and Ales Festival, which highlights the outdoor and social opportunities in the community. Taylor and Smith are now partners in the Marietta Adventure Company, a bike and kayak shop and hub for outdoor activity, especially the growing network of mountain bike trails that extend from town into the surrounding hills and forests.

With hundreds of miles of trails, the area is already a worthwhile mountain biking destination. As a new wave of projects is completed, including a large one in the Wayne National Forest, it could make a claim on being world class.

That possibility exists because of a historical intervention from the public sector. After the iron smelting boom decimated the forests, the federal government bought hundreds of thousands of acres of abandoned land and paid back taxes to local governments. Depression-era Civilian Conservation Corps workers replanted the forests. Much of that land is now part of the quarter-million-acre patchwork that constitutes the Wayne National Forest.

An outdoor shop with a dozen employees might not seem like a cornerstone of an economy, but part of the hurdle Appalachian Ohio faces is the perception that it isn’t a desirable place to be. Helping the community access the mountains and the rivers is a step toward highlighting a desirable lifestyle. The downtown First Friday events, the Farmer’s Market, and public art projects do that, too. So do the renovated theater and music hall.

Discussion of entrepreneurship is often focused on launching the next billion-dollar tech company. But small businesses that stay small make up the bulk of the country’s companies. Larry Fisher, executive director of the Appalachian Center for Economic Networks (ACEnet), a nonprofit that works to build regional business capacity through network expansion, technical assistance, and increased market access, explains, “Growing a business to eight or ten jobs is doing your part.” He adds, “Being a local or regional success is great.” Repeat that process often enough and it’s a base for a sustainable resilient economy. For companies that want to keep growing, ACEnet can connect them to additional resources.

Last year, the Appalachian Partnership added to those resources with a regional Community Development Financial Institutions Fund (CDFI). It offers loans up to $100,000 directly and can partner with banks and other sources for loans up to $1 million. “In a rural area, developing a relationship with a commercial bank is very hard,” says John Molinaro, Appalachian Partnership’s CEO. “For loans under $1 million, Chase makes decisions by algorithms.”

Other entrepreneurs in the area are focused on social enterprise. With Appalachian Regional Commission funding, Ohio University created the Social Enterprise Ecosystem (SEE) program to support the approach, including a model that helps quantify social returns, so the enterprises can communicate impact in a way that is relevant to both philanthropy and venture capital.

Serenity Grove Recovery, a nonprofit that offers transitional housing for women coming out of addiction treatment, used the social return model to get the funding needed to become the only such facility in the area.

Drawing on research done at the university, Rural Action, a nonprofit that promotes social, economic, and environmental justice, is taking an entrepreneurial approach to environmental remediation. Acid mining drainage is a common issue in coal country. Waterways can be turned the pH of vinegar; a ferric precipitate often turns everything a toxically gorgeous orange. Rather than simply removing and disposing of the precipitate, Rural Action is working with a paint manufacturer to supply it as a pigment.

Is It Enough?

Even creative economic development can only go so far. Michelle Decker, Rural Action’s CEO, worries the best efforts of business, nonprofits, local and state agencies won’t reach enough people without additional external funds to scale those efforts. She points out a sad irony in the intractability of Appalachia’s challenges. “We are on the cutting edge,” Decker says, which means that those who have piloted promising solutions to the challenges facing poor and rural economies in Appalachian Ohio may find they have communities in need of their expertise all over the country. “Look across the United States and you see a lot of poverty, limited access to healthcare and education, a lack of infrastructure. You see communities with money continue to win and succeed while those that need help fall further behind.” (In fact, since her interview, Decker has moved to California, after 10-plus years at Rural Actions, to lead a community foundation serving Riverside and San Bernardino counties.)

There are manifold efforts at building economic strength in the region: the restoration of a town’s once-glorious opera house, the dogged development of one industrial park which has allowed the purchase of a second, the mayor building hope from a hospital and herringbone sidewalks, the Appalachian artisans turning table legs destined for high-end New York hotels, the engineer-turned entrepreneur with designs to dominate a global market. Can they tip the balance against a history of disappointment and deep poverty?

For some economists, the regional focus itself makes it hard to give equal weight to all viable options. “If you are thinking of economic development as development of the people, not the place, it could be their future is somewhere else. The kind of welfare improvement that comes with migration is often much greater than the sum of everything else we try to improve livelihoods at the origin,” says Yale development economist Mushfiq Mobarak. “As the structure of the economy and the nature of jobs has changed, the places that used to be hubs for employment no longer are. Providing opportunities for people to move to other areas should be part of our policy toolkit.”

In many places around the world, the data show that segments of the working age population will be better off if they migrate to opportunity. That isn't an easy message for local leaders to hear. Or families for that matter.

David Wilhelm, for one, plans to stay where he is. He sees promise in Appalachian Ohio on a number of fronts. Trends, he believes, are turning in the region’s favor. “For 50 years, bigger was better,” he says. Huge farms. Massive factories. Urbanization. “Large-scale doesn’t work in Appalachia. The post-World War II model for the U.S. economy didn’t leverage what Appalachia has. Those systems are breaking down. We’re seeing local food, distributed energy, and community healthcare. These approaches play to Appalachian strengths.”

Wilhelm points to evidence to back his theory. American Electric Power, the same company that once operated Big Muskie, put out a request for proposals for 400 megawatts of distributed solar generation in Appalachian Ohio. Wilhelm is a partner at Hecate Energy, which has put in a proposal. He hopes his firm is chosen, but ultimately, “someone is going to win and build this in Appalachian coal country.”