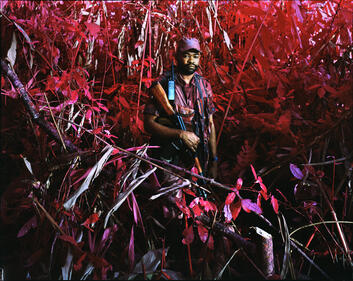

What Does Globalization Look Like in Eastern Congo?

Photographer Richard Mosse uses an unusual combination of technologies to tell the story of the conflict in eastern Congo.

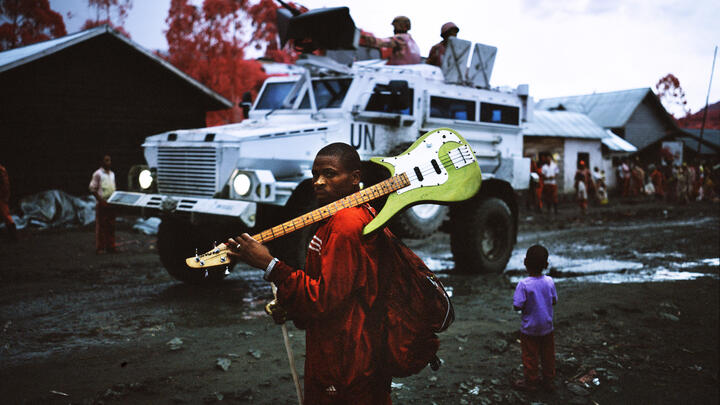

A Congolese musician in the town of Mweso watches as a convoy of United Nations peacekeeping troops, escorted by attack helicopters, withdraws from their camp at Pinga to reinforce other regions.

by Ben Mattison

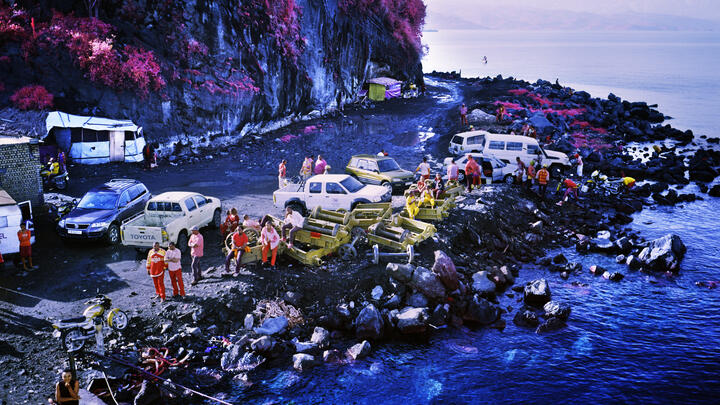

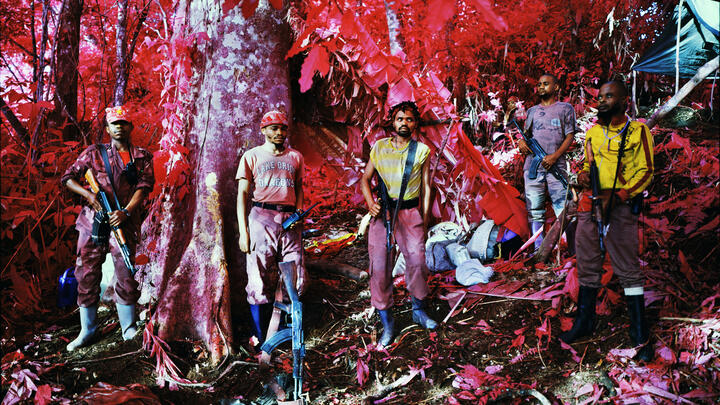

Globalization has an impact even in a place like eastern Congo, where connections to the outside world are weakened by the ongoing violence, poverty, and crumbling infrastructure. We asked photographer Richard Mosse ART ’08 to share some of his work there, and in the resulting images, you can see tendrils of the global system. The warlord hiding deep in the forest talks on his cell phone and refers to a copy of a report written by Human Rights Watch. The man panning for gold by hand will sell what he finds to middlemen and on, eventually, to the global market. UN peacekeepers flit through towns and villages. Even the workers cutting down trees to make charcoal are part of a tangled series of causes and effects with significant implications for the global challenge of climate change.

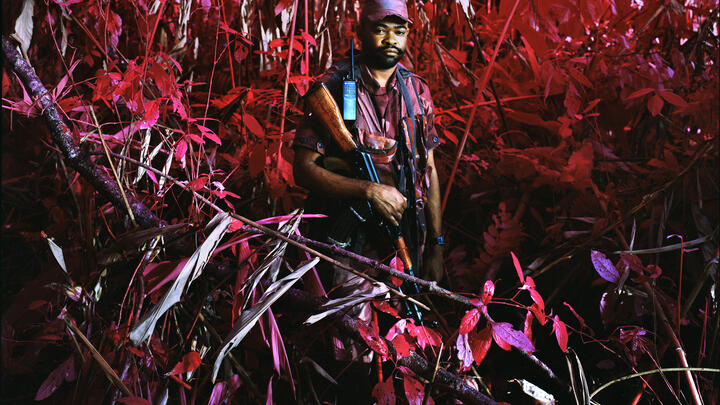

Mosse has been taking photographs of the conflict in eastern Congo since 2010, capturing potent images using a combination of older technologies.

He shoots with a large-format bellows camera, a nineteenth-century design executed in the 20th century by camera maker R.H. Phillips, and uses Kodak Aerochrome, a discontinued infrared film that was used for military surveillance during World War II and the Vietnam War. Intended to isolate human bodies among foliage, it renders infrared light as bright pink. Since the chlorophyll in living plants reflects infrared light, plant matter appears pink; other objects absorb infrared light and appear more or less as they do to the naked eye.

“It’s a very unusual, eccentric film format,” Mosse says, “It turns colors inside out.”

Because of its otherworldly appearance, Aerochrome was adopted by the psychedelic movement—on the cover of Jimi Hendrix’s album Are You Experienced, for example.

“So you had this tension at this historic moment, a tension in the medium where it was being claimed, appropriated, used, and manipulated by both sides: by the anti-war movement, on album covers and posters, and simultaneously by the U.S. military to actually target the Viet Cong,” Mosse says. “I really wanted to bring all of that baggage to bear on my work in the Congo in order to think about war photography—not simply to critique it, but to find alternate ways to tell stories.”

Historically, Mosse notes, war photographers have avoided “over-aestheticizing” their work. “It's a very codified way of representing the world,” he says, “for a very good reason—because you're dealing with human suffering.”

But, he adds, “in my opinion, aesthetics—in other words, beauty—has a great role to play in telling a story and communicating. Beauty, in my opinion, is the sharpest tool in the box of communication. So if you disregard the aesthetic potential of photography in trying to tell these stories, I feel that that's a mistake.”

In addition to showing in galleries and receiving attention in the media, Mosse’s work has taken on a second life on social media. With its intense colors, the series is particularly striking on a backlit computer screen. “It kind of got out of my control, in a nice way,” he says. “That's how photography works.”

But on the internet, it’s easy for the visual imagery to become separated from its context. “I try my best to contextualize the work and to anchor it to the narrative of eastern Congo,” where an estimated 5.4 million people have died of war-related causes, he says. “That's not just the people getting killed by bullets. That's also sickness, malnutrition, hunger, displacement, and exceptionally high mortality rates. But we don't really hear about it in the Western media as often as it warrants.”