Beauty, Power, Art, and Finance

Art, money, and power twist together in complex ways, in a dynamic that may be older than humans. In his research, Yale SOM’s William Goetzmann traces the social meaning of art and money and the ways they set pecking orders, create art superstars, and blow up into senseless bubbles.

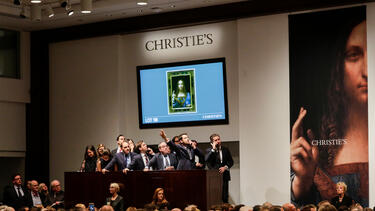

The auction of Leonardo da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi at Christie’s in 1997.

Q: What is the relationship between art and finance?

The relationship between finance and art has always gone both directions. In a practical sense, artists have long depended on patrons, especially in order to produce large works. And the patrons used their public displays of wealth to move up the social pecking order.

You could even say that the relationship is older than our species. There’s a 250,000-year-old hand axe found in Britain that was knapped so that a fossil shell sits right in the middle. It clearly has both a utilitarian purpose and a sense of the aesthetic.

Other archeological finds of tools and decorative objects from the Middle East and South Africa demonstrate our pre–Homo sapiens ancestors were interested in beautiful objects. A recent exhibition by the Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas collected aesthetically extraordinary tools and stone figures going back 2.3 million years.

Q: Where does the finance come in?

Some of these Stone Age tools are made from exotic materials. That suggests there were trading networks in antiquity, just as there are now. For economists, getting out of the mindset of people always optimizing their economic lives is not an easy leap. But through my career, I’ve tried to recognize non-pecuniary valuation—when people love something and want it, even if it’s not something that’s going to provide food or shelter, they’re willing to value that.

Aesthetics were, undoubtedly, part of the exchange process. “Hey, I like that stone with the fossil in it. Here’s what I’ll give you for it.” Why is art, aesthetic judgment, and aesthetic valuation such a fundamental part of the human experience?

One of the things I’ve been interested in lately is not just the broad relationship between art and finance, but looking specifically at the interaction between art and money to examine the social role of money.

Q: Would you explain that more?

Some of the most beautiful works of art from the Shang and Zhou dynasties in China are bronze vessels. They are often decorated with stylized animal figures and stand on elaborately detailed legs. But, when you look inside, the bottom is inscribed with something like the specifics of a land transfer. Is it a work of art? Is it a public record? Is it money—an item that’s given by one person to another as a transfer of value in exchange for another thing of value? Through much of human history, when big things are exchanged they have an aesthetic quality to them.

You also see it in the extraordinary variety of 19th and 20th century West African metallic currencies. They included everything from simple bracelets to elaborate necklaces cast with lost-wax processes. These objects are money in the sense that, in certain tribal settings across West Africa, they can be used for dowries or even as payment for large transactions. But because each item is decorated differently, no two are alike and the gradations to the quality of art changes their value—they’re nonfungible in that sense. So is it art or is it money? I’d say it’s somewhere in between.

If you think about a coin, it’s totally fungible. You do your day’s shopping in the market. Once the coin transfers from one person to the other, there’s no record. There doesn’t need to be. But with events that should have a memory, that will be referred back to, it makes a certain sense to employ works of art that are both money and aesthetic symbols. I think it’s exciting to see these objects serve as currency but also become invested with a particular history.

Q: You’ve pointed to ways that art plays into social hierarchy. How do art collections become a type of power?

One social function of owning art is to prove that you are important. In the 17th century, England was a backwater. Trying to rise through alliance, the prince who was to become King Charles I spent eight months in Spain trying to negotiate a marriage to Princess Maria Anna, whose brother was King Philip IV, one of the most powerful monarchs of the era and a famed art collector.

The negotiations failed, but Charles came away with the understanding that to command respect in this milieu of European royal families, you needed a great art collection. So he sent his agents out to acquire thousands of paintings and sculptures, including works by da Vinci, Raphael, Titian, and Rembrandt.

Some research I co-authored with Elena Mamonova and Christophe Spaenjers showed that across centuries, social competition is a driver for record-breaking prices at art auctions. And the competition can overtake the aesthetics. Records are often set for works that aren’t seen as the masterworks of a great artist or for works by artists who aren’t masters.

Catherine the Great paid extraordinary, record-breaking prices for art because she could. She bought artists who are no longer well-known—and, unfortunately, the boat bringing them to Russia sank in 1771. A Saudi prince bought a painting believed to be by Leonardo da Vinci for $450 million in 2017. And in between those price spikes were periods when American entrepreneurs of the late 19th and 20th centuries and Japanese buyers in the 1980s left their mark by setting record prices.

Collecting art allows the very wealthy to represent themselves as caring about a higher purpose, aesthetic issues, and so forth. And it is also clearly using art to establish hierarchy.

Q: Appreciating art is sophisticated. Owning art is power. What about making art?

There’s a very longstanding tradition of artists making a living through being entrepreneurs. The vases created by Praxiteles during the high period of Greek art are signed. Why? Because it creates a demand for work by that artist.

Reading about Michelangelo’s negotiations over subject matter and how much he was going to get paid, it’s clear that he’s a professional responding to the demands of the market. His frescoes on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel are obviously a masterpiece, but they were also the result of the Pope needing to decorate a room.

For every artist elevated to superstar level, there are hundreds of people making much more interesting art.

The pressure created by making art to satisfy a buyer is not a bad thing. We are all of us in a social context. And the stimulus of demand and expectation about what the product must be can lead to very creative outcomes. My wife’s an architect. Architects always have a program that they must respond to. Does that mean that the art is commercial? Yes. But we still get amazing architectural masterpieces.

Rembrandt painted portraits on commission. He developed a distinct style in order to create a brand. And for most of us, the most reliable way to distinguish a painting by Rembrandt from a painting by one of his students would be to look at the price. Which raises the question, if the aesthetics aren’t that different, why is the student’s painting worth so much less? Rembrandt did a good job creating a brand. That particular feature of art as a business has been long lasting.

Q: Do art markets reward the best artists with the highest prices?

Sometimes the artists that the culture has acclaimed to be superstars truly are extraordinary, but my work on superstardom in the world of art made me skeptical that it’s the norm. That acclaim is more like winning the lottery. For every artist elevated to superstar level, there are hundreds of people making much more interesting art.

But that’s not new. Why do we revere Cezanne? It’s clearly interesting art, but how much is purely aesthetic and how much is culture telling us who to admire? I don’t know that we can separate those two things, but I absolutely believe there are many more artists of great talent than the ones that have been recognized widely.

Any art sold at auction was made by artists who have had success, yet even within that select group most of the money goes to a tiny sliver of people. Artistic talent isn’t distributed that unequally. Art at the highest level is pretty much a social process of coordination around choosing the coolest thing.

Q: You have done work looking at this issue through the lens of gender.

The Yale School of Art has historically produced many significant artists. I studied the careers of men and women who got MFAs from Yale. The superstar effect—the concentration of market value in the work of a few artists—is even stronger for the women than for the men. Why? One hypothesis is that the market is not so certain about the quality of the art that women are producing, so the few women labeled worthy receive an extraordinary boost.

There are now some stratospheric prices paid for art made by women. In part that’s because museums have finally been shamed into recognizing their long-standing failure to collect works by female artists and are trying to make up for lost time. But even so, the prices for the superstar women are nowhere near the prices paid for art by men.

And if we look just at the period since 1983, when Yale MFA graduates have been roughly 50% women, female graduates have lagged in cultural recognition. Forty-plus years should have been plenty of time for the imbalance in recognition to have worked itself out through the culture, but it hasn’t.

Q: How did art become an area of focus for your work?

Making art is something that’s always been part of my life. In college, I published a book of drawings—scenes from Yale and New Haven. Later, I got interested in painting and took it up. After college, I did a year of art history graduate school and worked as an independent producer for public television doing projects that touched on art, artists, and archeology among other things.

In 1984, I was a student at Yale SOM when I was asked by a very wealthy entrepreneur to help him start a museum of western art in Denver. He owned more cattle than any other person in the world. He also owned some of the greatest works of western painting—Frederick Remington, Charles Russell, Albert Bierstadt, George O’Keefe, and many more. He liked that I had a background in the arts and some business education.

I ran the museum for a while and when I returned to finish my degree at Yale SOM and continue on to get my PhD, I had decided to focus on the intersection of art as an aesthetic item and art as an investment.

That made me part of a very small group of researchers asking those kinds of questions. It’s been a great group to be part of and has allowed me to do work related to museums, trends in art prices, and the weird bubbles that happen in the art world.

Q: Museums are venues for engaging with material objects. Part of what is exciting about seeing a painting is knowing the artist handled and labored over that canvas. Thinking about the books that you have authored and edited, even those that aren’t about art, they almost feel like bound museums—they foreground material objects in a way that encourages readers to inhabit and explore the historical moments being discussed.

Well, thanks for describing them that way. My background in art history and museum work and my love of aesthetic objects likely shaped my orientation toward material culture. But it was at least partly happenstance that led me to approach two books of financial history, The Great Mirror of Folly and The Origins of Value, that way.

I worked very closely with my colleague Geert Rouwenhorst on both of them. We have collaborated on financial history for 20 years. When Yale established the International Center for Finance, we were given a space in a gorgeous, renovated house on Hillhouse Avenue. When we were asked what should go on the walls, both of us owned some defaulted bonds from the 19th century that were beautifully designed. Without much thought, we suggested buying a bunch more. We got most of them on eBay and maybe a few from dealers but basically the framing cost more than the bonds.

But once they were on the walls, walking past them day after day, we’d be struck by questions: This is a German bond from the hyperinflation period of the 1920s. The money that it promises is useless, so how could a bond be issued at all? What was the collateral of this Chinese bond? Why could they hypothecate inland tax revenues?

A formal education in financial history typically uses a top-down timeline concept, but we learned by asking questions about the objects themselves. And what we found as we dug into these old financial contracts fascinated us.

A very generous anonymous gift allowed us to work with Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library to buy some financial history treasures, including a bond from 1648 issued in the Netherlands that is still paying interest. It sends shivers up your spine; this amazing bond— issued to pay for a little bit of repair on a specific bend in the lower Rhine that you can still go and see—has never defaulted. That bond is part of The Origins of Value.

We also acquired some certificates that were prospectuses for crazy bubble companies that were being started in the Netherlands in 1720. Studying them helped us develop The Great Mirror of Folly.

And when I teach my course on financial history, I bring in material objects—coins from different places and eras as well as financial documents, everything from cuneiform contracts for land transactions, to loans on life annuity contracts issued to knights in the 15th century, to Chinese bonds that defaulted in the Cultural Revolution.

My aim is to have students touch these objects and ask questions about what they reveal. They choose one object to write about for a term paper, but I insist that they write it from the bottom up. What is the document printed on—paper or vellum? Why? What does that tell us? Who are the people that signed it? What do we know about their lives? It’s a way to make sure students understand a stock or bond isn’t just an abstract concept; these are things that were embedded in people’s lives. The paper may eventually touch on historical moments, but it starts with a specific document that meant something to specific people.

I think it’s an effective way to teach history, and I’m glad it works its way into my books, too.

Q: You have done work on historical market bubbles. How does the NFT bubble compare to them?

We lived through a financial bubble that was bigger than the tulip mania in 17th-century Holland. During the COVID era, NFTs went through an extraordinary boom that went up higher and just as fast before exploding in just the same way.

The tulip bubble was an interesting social phenomenon where the prices of certain types of tulip bulbs were bid up to incredible levels. A tulip bulb that would produce a flower with certain striation would sell for as much as a house. Why? It was stupid. There was no sound reason. But in the mania people saw a chance to make a lot of money. There was a craving for a mechanism to get out of the life that you’re in and into a very privileged one.

And during COVID, while everyone was caught at home, we saw the same thing play out with NFTs. Mike Winkelmann, who is better known as Beeple, created Everydays which is a digital collage composed of 5,000 cells made from individual pieces of art made over 5,000 consecutive days. It’s an interesting piece of art, but when it sold at auction for $69 million in 2021, suddenly everybody saw a speculative gambling opportunity: “If I buy the right NFT, I could sell it and retire.”

The crazed rush to get in on the phenomenon meant a lot of the NFT art was terrible. In fact, the Bored Ape Yacht Club NFTs were aggressively stupid and intentionally ugly. The approach was, “I can make you pay millions for a piece of garbage.”

Undoubtedly, there were some people that were able to retire on speculative profits, but it was mostly an interesting social phenomenon.

Q: What has your interest looking forward?

I’m fascinated by the way technology is changing who is an artist and how art fits into our lives. Museums democratized art in one way, but they are also sanctums. Art is something we go to see; it is something apart from everyday life. But since the internet, a significant fraction of humanity has come to feel empowered to think of themselves as producers of art.

Whatever your views about whether the art that people are making and putting on Instagram and other platforms is good or interesting, the fact that it is happening is remarkable. The sudden adoption of tools that let people create virtual galleries, the way creating them and visiting others has been integrated into our daily lives, the way they have become places to share experiences and to give feedback—it’s a fascinating shift in who is an artist and where art fits in our lives. It has been revolutionary, and I’m curious to see where it goes.

However, as to whether achieving status through art acquisition manifests itself in the social media of art. I’m not sure it does.

Social media has created its own pecking order of influencers and follower metrics. With the notable exception of Mike Winkleman—who has more than two million Instagram followers—artists have yet to achieve superstar internet status. Top collectors have even less social media presence. Status collecting has not yet gone virtual. The timeless human act of acquiring, owning, displaying and enjoying tangible works of art appears to be alive and well.