Creating the Bilbao Effect

The startling success of the Guggenheim Bilbao, which launched in 1997, spawned a new term: “the Bilbao Effect,” as shorthand for the impact a cultural institution can have on the surrounding city. Thomas Krens ’84, Gail Harrity ’82, and others who were present at the inception look back on how industry, marketing, government, art, and architecture came together to make history.

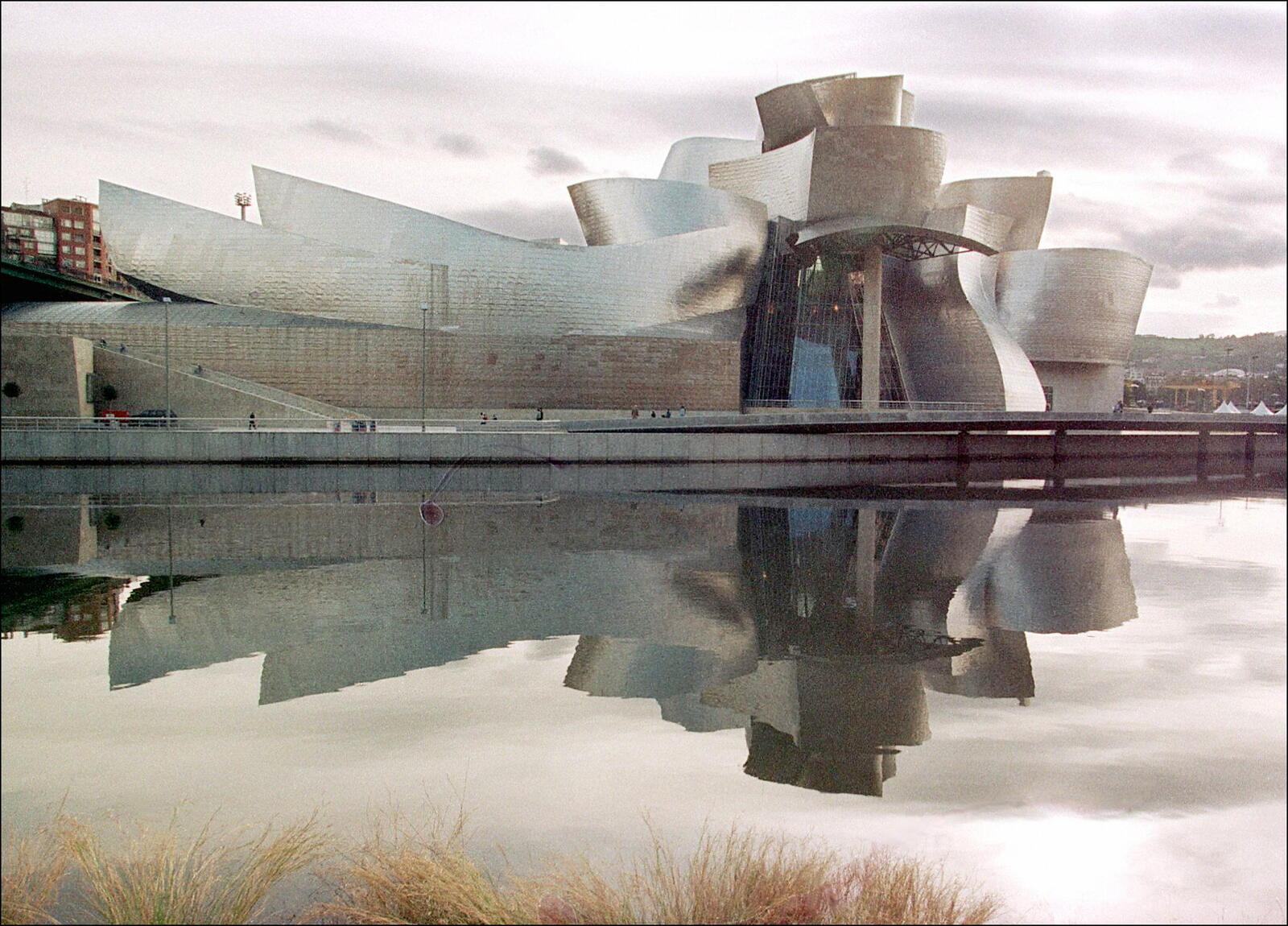

The Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, in February 1997.

For those involved, building the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao was a career- and life-defining experience. Their ambition to create an architecturally iconic structure to house an extraordinary museum was fully realized—and its impact far exceeded expectations.

Yet they understood that a fine art museum in a small Spanish city could only draw millions of visitors and become a symbol of economic revival because it was one beautifully executed project within a larger, multi-decade strategic effort to transform Bilbao and the Basque Country.

While many hoped the Bilbao Effect had a formula, it’s more realistic to believe Bilbao’s success stemmed from a unique convergence of factors including the desperation born of economic devastation in the Basque Country’s largest city and the unusual financial autonomy of the regional government, which had the power to set and collect its own taxes. This combination enabled disciplined execution of bold, innovative solutions, turning visionary ideas into a lasting urban transformation.

Thomas Krens ’84: Bilbao burst onto the scene like a meteor.

Gail Harrity ’82: It changed the entire concept of museums as not only repositories of spectacular works of art, but as economic engines that can revitalize communities.

Carmen Giménez: The idea of Tom Krens, which was brilliant, was through art you change a city. This museum transformed Bilbao. It was a dirty, sad city full of smoke. If you go there today, it’s a beautiful, fashionable place full of people who come from everywhere.

Pablo Otaola: For most people, the Bilbao Effect is the Guggenheim. It’s true the museum made the city suddenly look different. It made people outside start to see what was happening in Bilbao. But urban planners know that before the museum, there were major projects that made everything else possible. And important public works continued after the museum opened.

Frank Gehry: Bilbao was a miracle, and it involved more than my building. It involved redoing a lot of infrastructure and buildings by other architects, so it’s not just one thing. It takes a political commitment, a big political commitment. (Source: MARTa Herford Museum)

Juan Ignacio Vidarte: If the museum had been the only project, it would not have had the same impact. If Bilbao hadn’t cleaned the river, built the subway, and moved the port, the museum would not have succeeded. The museum was not the most important investment. It was not the most expensive investment. But as an element of a broader plan, the museum was a catalyst that allowed something none of the other initiatives would have achieved without it.

What is the Bilbao Effect?

Krens: It’s economic impact.

Vidarte: A term that has been very much misused.

Harrity: I think the biggest factor might’ve been the entrepreneurial thinking of the Basque government. I remember asking the minister of finance, “How did you decide to invest as much money as you did?” His response was, “I had a choice. I could build three more kilometers of the highway from San Sebastian to Bilbao, or I could invest in a project that had the potential of changing the image of our country.”

Krens: It wasn’t just something that we were going to be the sole mechanism for turning around Bilbao….We became in effect, the poster boy for the renaissance of Bilbao….I don’t think that they could have or anybody could have predicted it, but nevertheless, it was a fortuitous development that was built on top of an intelligent response to the condition that the city was in. The renovation of the Basque Country and Bilbao was underway before I got there. (Source: The Week in Art podcast)

Juan Ignacio Vidarte

What Bilbao needed

Vidarte: For centuries, Bilbao was an important, wealthy city within Spain. It was a center of finance. It was one of two centers of the industrial revolution in Spain. Bilbao for iron and steel making. Barcelona around textiles.

The Bilbao I grew up in had a lot of industry, a lot of activity. It was not a tourist destination because it was a very polluted city. In the later part of the 20th century, steel making and ship building underwent a structural decline.

Otaola: I remember how gray and industrial the city was. How the river smelled bad and was nearly solid.

Vidarte: It wasn’t clear what the future of the city would be. It was also a moment of political violence because ETA, the Basque terrorist organization, was very active.

But Bilbao had always had a strong sense of its own character, so there was a sort of soul searching. Both the public and private sectors worked to define priorities that would help steer change. Because I was in charge of tax and financial issues for the province, I was part of a public-private brain trust developing plans.

Otaola: Sometimes I think what happened would be impossible today. With industry gone, with unemployment, and no sense of a future, the politicians did something that is very rare in Spain, perhaps rare anywhere, they worked together, they found consensus around solutions for the people, not for their own interests.

Vidarte: Spain had just joined the European Union in 1986. A number of priorities were developed to improve the city’s place in a new geopolitical context. Most were necessary and straightforward: improve the environment, communication, education, the workforce. But one of them was unusual, strengthening the cultural centrality of the city.

It was a very rough concept of developing cultural institutions with the capacity to attract an audience from other parts of Europe. The goal of making Bilbao a destination was there, but how to get to that goal wasn’t at all clear.

What the Guggenheim needed

Krens: I can’t say that I had a vision fully formed before I started, but I spotted very early on a very simple fact: expenses were going to outstrip revenues.

Harrity: The Guggenheim didn’t have an endowment, so, financially, we had to do something innovative.

Krens: I had to find other ways of making money.

Harrity: The competition among New York museums always placed the Guggenheim behind the Met and MoMA, but it had three strengths: the collection, architectural excellence, and an international footprint.

Krens: The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation also owned the Peggy Guggenheim collection in Venice, which by definition made it international.

Harrity: Most pressing for me, as the deputy director for finance and administration, was figuring out how to finance and complete the desperately needed renovation and expansion of the Guggenheim's Frank Lloyd Wright building in New York.

Krens: I saw that the museum’s strengths could be developed to another level. Economies of scale. You could run two museums more efficiently than one, three museums more efficiently than two, because you could share programming, curators, staff. You could reduce overhead costs by not duplicating a whole universe of expertise in every museum that you had.

Harrity: The board recognized that the museum needed to continue to evolve. There was even a sense that, if you’re not a living, growing institution, you’re a dead institution.

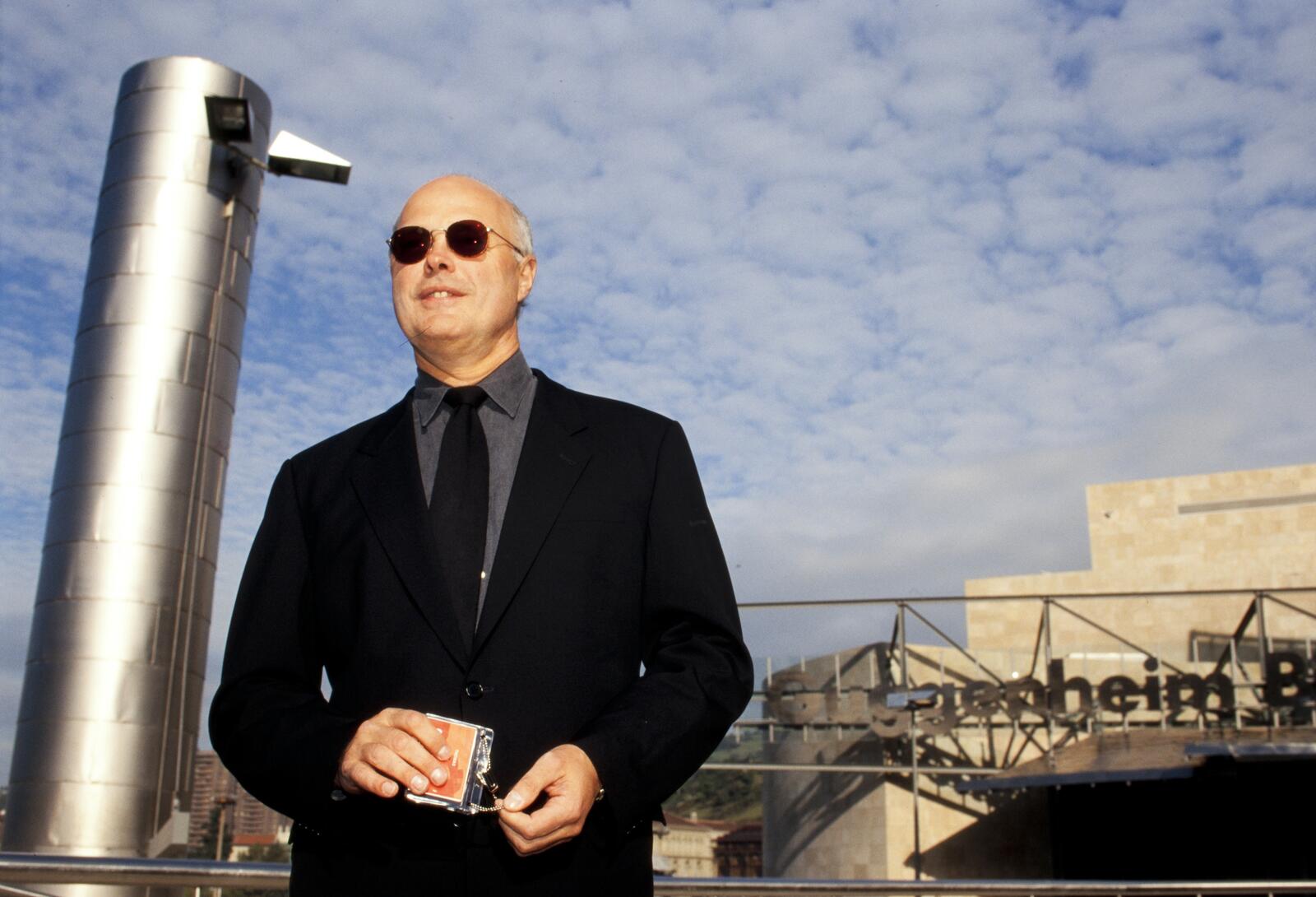

Thomas Krens

Making the connection

Vidarte: We learned about the Guggenheim’s interest in international expansion by chance. The Guggenheim in New York was closed for renovations so masterworks from the collection were touring. The first venue of that tour was Madrid for the reopening of the Reina Sofia, the national contemporary art museum. It was a major event.

Giménez: I opened the Reina Sofia while I was advisor to the Minister of Culture. Tom Krens came. He loved it.

Krens: I immediately hired Carmen.

Harrity: Carmen, Germano Celant, and Mark Rosenthal were all hired as international curators. That was quite revolutionary—Guggenheim curators living in different countries.

Vidarte: Tom Krens was in the Spanish press explaining his ideas about building a Guggenheim museum in Europe. We thought, what if Bilbao were the venue?

Krens: It became clear that Venice was not going to move anytime soon. So, we put a certain amount of energy into Salzburg.

Giménez: I was helping with the proposed Salzburg project. It could have been something exceptional for Austria, but eventually it was clear that it wouldn’t happen. It was not essential for them.

Krens: I started looking at Spain. I quickly insinuated myself with some of the top people in Madrid. My idea was to build a Guggenheim there.

Giménez: We talked to the Banco Bilbao Vizcaya about supporting the project. But Madrid had too many museums already. So did Barcelona. A colleague from the Ministry of Culture and a very good friend, Alfonso Otazu, was Basque. He said the region needed something like this. I brought the idea of Bilbao to Tom.

Krens: When I was asked would I consider doing a museum in Bilbao, to tell you the truth, I didn’t exactly know where it was.

Harrity: We literally had to look up where Bilbao was on the map.

Krens: I knew that there was some reference to Bilbao in a Bertol Brecht play. I knew there was terrorism and jai alai, but that was about it. So, I said, I just don’t see the fit.

Giménez: Alfonso also told us something which was essential. He said that if we went through the Basque ministry of culture the project would never happen. He said, “Go with the money. Go to the ministry of finance.”

Krens: I was persuaded at least to go to Bilbao.

Vidarte: Each of the Basque governmental institutions involved had different priorities for the project, but they understood that they had to be completely aligned in their discussions with the Guggenheim Foundation. Somehow, they managed.

Krens: The airport was a landing strip with a shed beside the tarmac. When the plane parked on the tarmac, I went down the steps and there was a red carpet to a helicopter. Juan Ignacio Vidarte met me. He explained that we would be flying over Bilbao to the capitol of the Basque Country, Viscaya, which is a small city, just south, to meet with the Basque president.

The president says, “We want to have a Guggenheim museum in Bilbao.” I’ve still never even seen the place. I understood building museums to be complicated projects, particularly on the funding side. They take time, so I was intrigued when he asked, “What will it take?”

At that point I had done so many feasibility studies, I knew. I said, it would cost you $320 million: $150 million for a building, $50 million for a new contemporary collection to complement whatever the Guggenheim Foundation loaned the museum, $100 million to fund 10 years of operations, and a $20 million upfront, nonrefundable down payment, which was a fee for the Guggenheim brand and insurance against my political assassination, quite literally.

I told him, on top of the financial investment, the Guggenheim would have to be completely in charge of anything that was associated with the Guggenheim name—the collection, the programming, the architecture, and the construction.

He said, “Yes.” He put his hand across the table. So, that was that. I’d never had a client who moved that fast. But by that time, I’d done my homework on the Basque. I understood that they did what they said they were going to do, no matter what.

Vidarte: Tom had the vision, and he was brave enough to act on it. It took courage to explain to a board of trustees in New York that you want to do an expansion project in Bilbao, Spain, a place most of them had never heard of.

Moving fast

Vidarte: The Basque governmental institutions didn’t want it known that they were considering a project, which could have been perceived as fantastical and unrealistic. So, for most of the time, the discussions were highly confidential and moved fast. From the first conversation in April 1991 to ratifying the agreement in February 1992, it was nine months.

During that time, it became clear to me that the Guggenheim would be a very good partner, not just because of their vision and how well it aligned with what we wished for Bilbao, but also because of the type of institution it was—a non-political, not-for-profit that wasn’t huge. It was flexible and could, as was shown, adapt to what was needed.

The agreement was straightforward. We defined a goal of building a museum of international reputation aligned with the Guggenheim to open by 1997.

Krens: I agreed that we wouldn’t go over budget.

Vidarte: I was asked to develop a blueprint of what would be needed to open the museum on budget and on time. I suggested that we set up a temporary entity, a consortium that represented the different governments with a single voice. They thought it was a good idea. They suggested I lead it, and I accepted.

Vidarte: The architect was chosen through a competition.

Krens: I selected three architects, one Asian, one European, and one American, to take part in a competition that we did at lightning speed. The architects got one site trip, four weeks, and no instructions for deliverables. There were seven people on the panel. The Basque had four votes. The Guggenheim had three.

Vidarte: At that time Frank Gehry was an architect mostly known to other architects. But it was very clear to the panel that he best understood the nature of the site and the different goals this building was meant to fulfill in addition to being a museum.

The Bilbao Effect 1.0

Krens: This thing was severely criticized when we announced it. The Guggenheim is going to do a museum in the Basque Country? How desperate is Tom Krens?

Vidarte: The project, at that time, was very controversial. The economic situation was dire. It wasn’t self-evident that the best way to use public funds was to build a museum rather than support ailing industries or any number of other priorities.

Harrity: Some people in the Basque region saw us as American imperialists coming into their city.

Krens: I’ve generated probably more press than any museum director ever, and a good part of it negative.

The Site

Vidarte: The Guggenheim Foundation believed the building needed to be architecturally iconic in order to make sure that the museum spoke to a worldwide audience.

Harrity: The city was looking at repurposing a historic building. Retain the exterior envelope and basically plunk a museum inside it. It could have been a science museum or a history museum or whatever. It didn’t matter. They wanted any cultural institution that would create job opportunities for young professionals and stem the brain drain.

Vidarte: It became clear that it wasn’t possible to both transform that building and preserve its historic character.

Gehry: They took us up on the high wall overlooking the city and asked us where we would put it instead. We showed them where the bridges intersect, and the river turns. There’s so much stuff happening there already, it would be a great spot. (Source: Conversations with Frank Gehry)

Krens: There was the issue of the site. They had a site, and I said, no. I had done this run through Bilbao, and between the university, the opera, and the Museo de Bellas Artes, there’s this triangle of land beside the river.

Vidarte: It’s one of these elements of mystery in a project. Did the first notion about the site come from Frank or Tom? It’s really unclear.

Harrity: Frank and Tom argue over who found it. Tom says he found it jogging and Frank says, no, no, no. Having sat between them when they’ve argued over who found it, I give them both credit for agreeing the best location was that spot on the Nervión River.

Otaola: After the Olympic games in Barcelona and the World’s Fair in Seville, both in 1992 and which both cost a lot, public funds were difficult to access. Bilbao Ria 2000 was set up to move forward on the city’s strategic plan. It was a publicly funded, private firm. The four levels of government—city, province, region, and national—were the shareholders. They gave us a very small budget, and they gave us land.

Sites that the national railway and the port authority no longer used were donated to Bilbao Ria 2000. We acted as a public developer. Each project funded another, eventually allowing us to finance one billion euros in projects including 35 hectares in the Abandoibarra zone where the Guggenheim now sits.

Frank Gehry, Thomas Krens, and Gail Harrity during the construction of the Guggenheim Bilbao.

The Design

Vidarte: In the initial stages, these types of projects are very fragile, anything can derail them. So, it was important to build and maintain credibility.

Krens: It was a building that was meant to seduce even before anything was put in. Marilyn Monroe and sailing ships were some of the iconographies that we employed in trying to develop the shapes.

Vidarte: As head of the Consortium for the Guggenheim Bilbao Project, I understood my main role to be making sure that the building could be built on time and on budget.

Harrity: At that point, Frank had completed some projects that went over budget.

Gehry: We decided to make the building metal because Bilbao was a steel town, and we were trying to use materials related to their industry. So, we built 25 mockups of a stainless-steel exterior with different variations on the theme. But in Bilbao, which has a lot of rain and a lot of gray sky, the stainless steel went dead. It only came to life on sunny days. (Source: Conversations with Frank Gehry)

Krens: We had an incredible open process that never really ended. I was starting to go to Bilbao once a month and to Santa Monica, where Gehry’s offices were, twice a month. (Source: The Week in Art podcast)

Gehry: I was frustrated because nothing was looking right, and I was still struggling with it when I was in my office looking through the sample files. That’s where I found a piece of titanium. (Source: Conversations with Frank Gehry)

Krens: I would say that I had a significant hand in the design of the building in the sense that I was there all the time. I was an unusual client because most clients were not involved that much.

Gehry: I took that piece of titanium, and I nailed it on the telephone pole in front of my office, just to watch it and see what it did in the light…. As it happened, the day that I tacked it up, it rained in LA, which was unusual, because it wasn’t the rainy season. The little metal square went golden in the gray light, and I had another one of those Eureka! moments. (Source: Conversations with Frank Gehry)

Krens: One of the center points of the museum is the big gallery. It’s 30,000 square feet. It’s 432 feet long. It’s a monumental experience made even more monumental by Richard Serra’s sculptures. Now, the Richard Serra sculptures didn’t show up until 2003, but in 1992 I made the argument that the floors had to be strong enough to withstand 40-ton steel plates and that some doors had to be big enough and wide enough for things of this scale. (Source: The Week in Art podcast)

Gehry: The problem with titanium was that it cost twice what stainless did. We didn't think we could afford it. But we continued to work with the material and found that we could use it at half the thickness of stainless steel… and that got us back into the ballpark. We bid it as an alternate. (Source: The Planning Report)

Krens: There are certain architects who you cannot penetrate their design process at all. … Frank, on the other hand, he understood that he could take inspiration from substantial back and forth with the client, and if you said that you weren’t sure about something or you didn’t like something, he would go back as far as you wanted to. His logic was that you do it a second time. You knew more than you did the first time. The third time you knew more than you did the second time, and you eventually improve the outcome. (Source: The Week in Art podcast)

Gehry: Tom Krens is a genius. He has a vision. He’s got an ego, and he’s got his own thing, and he's fun to play with. He energizes me. I energize him. We inspire each other. And you can feel it. It’s exhilarating when you work with him. (Source: Conversations with Frank Gehry)

Vidarte: The building couldn’t just be a beautiful shape; it needed to work well as a museum.

Harrity: I think good decisions are often a reflection of multiple perspectives being brought to the table. And in this case, it was also multiple goals. So, the diversity of perspective and goals, along with the healthy back-and-forth, enhanced the outcome.

There were times when Frank would’ve made different design decisions, but the Basque really pushed back. And there were times when Gehry Partners or the Guggenheim pushed back.

Vidarte: I visualized it as a three-legged stool.

Harrity: The confluence of a nonprofit foundation, an architectural firm, and government, all working together, was really exceptional.

Gehry: [T]he Russians, during the beginning of the bidding period, dumped a bunch of titanium on the market, the price went down and actually came in under the stainless. It was enormous luck. (Source: The Planning Report)

Under construction

Vidarte: It was gradual, but as the building started to become more real, you could start to perceive that it was something special.

Krens: If you put the Guggenheim Bilbao next to the Metropolitan Museum in New York, it is just about as long and 50% taller. Imagine that on the edge of Central Park, and here it is in the midst of the Basque Country. If we’d built it at a quarter of its size, it would not have the same impact. Put it at this scale, and it's Chartres Cathedral. It’s awe inspiring. Jaw-dropping. No matter how many times people have seen it in photographs, they go there and are stunned by the majesty of it. (Source: Conversations with Frank Gehry)

Vidarte: In Spanish, Bilbaína is the word for someone from Bilbao, but it is also the term for doing something unexpectedly brave or brash. At the end of the 19th century the city expanded the port beyond a size that made sense. It became a major advantage in the early years of the 20th century. It made the city wealthy. The museum was like that, too. It is outsized for Bilbao. But in a way that makes a statement, in a way that makes the museum and the city special.

Harrity: The Basque mentality and entrepreneurship, it’s not just hard work, it’s creative thinking about the public-private partnerships that are so essential. They had the drive and focus to follow through on their strategic plan. They believe in partnerships enough to be willing to delegate.

Harrity: Frank was absolutely on target with the budget. And I think even more important the CATIA design system that Gehry’s team adapted from aircraft design software facilitated the engineering and allowed extraordinary precision in manufacturing the curved steel understructure of the building. That created an efficiency not seen in other projects.

A Richard Serra sculpture in a gallery at the Guggenheim Bilbao.

And a museum that works

Harrity: When I see a great exhibition on a wall of any museum, I know it couldn’t have come together without loans from many lenders. And they wouldn’t have loaned their artworks if the museum didn’t have the climate control systems and the loading dock and everything that’s required for excellent museum operations.

The infrastructure of a museum is core to the mission and invisible to the vast majority of people yet central to its success. While construction was happening, we developed a 10-year projection on every aspect of museum operations.

Vidarte: Often, those elements of the equation are not really thought about. But to be successful, there needs to be an operational model that is sustainable—that addresses the fundamentals of management, governance, and funding of the institution.

Gail was instrumental in that. She was very knowledgeable about how the Guggenheim operated in New York. She was also very flexible in approaching this new challenge. There wasn’t an instruction manual. There weren’t other cultural institutions that intentionally scaled to multiple locations. There was a lot of skepticism and opposition in traditional museums about the approach.

Opening the museum

Giménez: Tom Krens wanted me to be the director. I told him, it has to be someone who is Basque. It has to be Vidarte. And the museum has been impeccably run. It’s very well-administrated, everything is in order. It’s exemplary.

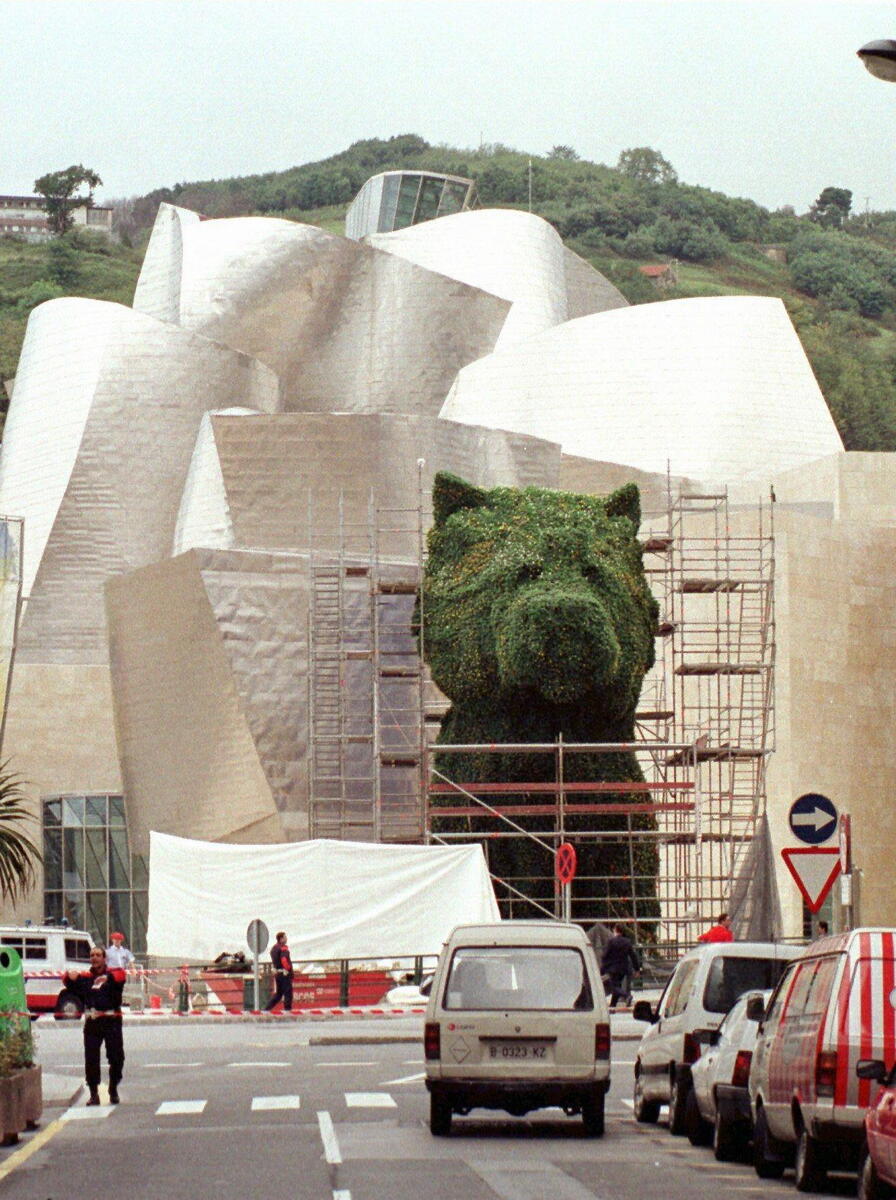

Police outside the Guggenheim Bilbao on October 13, 1997, after gunmen shot a policeman as he investigated a suspect van and explosives were discovered.

Days before the opening ceremony, ETA separatists, posing as gardeners, attempted to hide remote-controlled explosives among the flowers covering Jeff Koons’ 43-foot-tall sculpture Puppy, which stood outside the museum. The attack, aimed at killing King Juan Carlos and Queen Sofia, was stopped by police but one officer, José María Agirre Larraona, was fatally shot attempting to capture the men. The museum’s inauguration proceeded under heavy security.

Krens: Ever since that time, there’s been no terrorism in the Basque Country, which is coincidental or remarkable. Either the Guggenheim played a role in that, or it didn’t. But, I mean, these forces of normalcy were underway.

Vidarte: Someone told me the opening was headline news on CNN. I was totally surprised. How could a museum opening in a small city in Spain be news?

Krens: It took the world by storm. Two museums opened in the space of two weeks. One was Richard Meier’s Getty, and one was Bilbao which was completed at roughly one tenth of the cost. I mean, the Getty lost the race.

Vidarte: We built the museum because the world was becoming more international and we believed in the importance of culture, but we didn’t really understand what that meant, yet. It took time to realize that something happening in Bilbao could have global resonance.

Harrity: It became just such a huge deal. Frank will even say, it turned his career. When you have Philip Johnson calling it, “the greatest building of our time,” that’s big.

Vidarte: The feasibility study in 1991 foresaw attendance around 400,000 visitors per year with about 50% to 55% coming from outside Spain. We thought that it would take 10 years to grow that number. We opened with 1.3 million visitors, and we’ve never had less than 60% coming from outside Spain.

‘Do the Bilbao Effect’

Gehry: I don't like this term Bilbao Effect because people since Bilbao come to my office and want to hire me to do the Bilbao Effect. When I asked them what their program is, what their infrastructure is, what their budget is, what their schedule is, they say, “Don’t worry we’ll work that out later. Just make the Bilbao Effect.” I turn those projects down. (Source: MARTa Herford Museum)

Krens: Bilbao had a substantial, even a meteoric impact, but those are kind of once a century events. If even that. (Source: The Week in Art podcast)

Harrity: The museum was a project within a much larger strategic plan. The Basque put Bilbao on the global map. They created a destination for tourism. Here we are 27 years later, still looking at the economic return and the cultural return.

Vidarte: The way I understand the concept is that investment in culture can have effects far beyond culture. It can help transform a city or a region in economic and social terms. That’s certainly what happened in Bilbao.

I have been involved in hundreds of interviews with people from different parts of the world trying to understand the Bilbao Effect. I try to explain that the museum was a very important part of the transformation. It was a catalyst. When you explain this to many people, it’s clear they’re not listening, because of course, it’s much easier and sexier to say the Bilbao Effect is putting up a flamboyant building.

Otaola: I judged what we had done by how my mother and her friends—old people who spent their lives in Bilbao and had the city in their hearts—felt about the changes. They were happy. They liked the new Bilbao. The city went from being very pessimistic to feeling that anything is possible.

Vidarte: The city has always been resilient. Today Bilbao is prettier, more aesthetically pleasing. It’s certainly more cosmopolitan. But I think in essence, the city’s character remains quite unchanged.

Giménez: The Bilbao project changed the Guggenheim, too.

Krens: The brand was taking hold, and it was clearly a branding exercise as well. I felt that Bilbao would actually stimulate attendance in New York, which it really did.

I think, without necessarily blowing my own horn on this, that in terms of museums the Guggenheim is probably the second brand in the world after the Louvre. I mean, the Museum of Modern Art is bigger, and it’s more powerful. So is the Met, but to a certain degree, they have generic titles. The Louvre and Guggenheim have associations. They have a brand.

Harrity: It was Tom’s ambition. His vision. The team he put together. And the cross-fertilization that came from that.

Vidarte: To be given the opportunity to be part of a project from its very roughest conception to design, construction, and opening and then almost 30 years of operation and fulfilling expectation, I mean, that’s like a dream.

Harrity: I worked on great projects at the Met. I worked with Frank Gehry again in Philadelphia, but Bilbao ignited a spark for everybody involved. For the Basque, for the Guggenheim, for Frank, we gave birth to this extraordinary project that transformed not only the region, but certainly my life, as well.

Editor’s Note: This oral history is based on interviews conducted between February and April of 2025. Additional quotations have been used from existing published sources cited above.