Timothy Westmoreland: Healthcare at the Supreme Court

Subscribe to Health & Veritas on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, YouTube, or your favorite podcast player.

Howie and Harlan are joined by Timothy Westmoreland to discuss his long career in health policy and law, and the far-reaching consequences of the Supreme Court decision overturning Chevron deference. Harlan looks at President Joe Biden's debate struggles; Howie reports on the many healthcare-related Supreme Court decisions.

Links:

The Presidential Debate

Harlan Krumholz: “Did Cold Medications Affect Biden's Debate Performance?”

CNN Presidential Debate: President Joe Biden and former President Donald Trump

Press Briefing by Press Secretary Karine Jean-Pierre, July 2, 2024

“Biden's Evolving Reasons for His Bad Debate: A Cold, Too Much Prep, Not Feeling Great and Jet Lag”

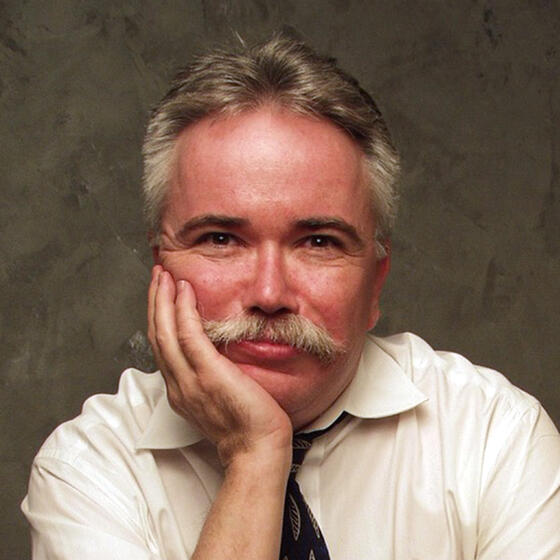

Timothy Westmoreland

Timothy Westmoreland: “Henry Waxman, the Unsung Hero in the Fight Against AIDS”

“LGBTQ History Month: The early days of America's AIDS crisis”

Cornell Law School Legal Information Institute: Chevron deference

Ballotpedia: Skidmore deference

“How the Chevron case has roiled U.S. healthcare agencies”

SCOTUSblog: Corner Post, Inc. v. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

“Supreme Court appears likely to allow abortion drug to remain available”

The Supreme Court

“Implications for Public Health Regulation if Chevron Deference Is Overturned”

Supreme Court opinion: Murthy, Surgeon General, et al. v. Missouri et al

SCOTUSblog: Food and Drug Administration v. Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine

Cornell Law School Legal Information Institute: Moyle v. United States

Supreme Court of the United States

Health & Veritas Ep. 77: Megan Ranney: What’s Next for Public Health?

Learn more about the MBA for Executives program at Yale SOM.

Transcript

Harlan Krumholz: Happy 4th of July. Welcome to Health & Veritas. I’m Harlan Krumholz.

Howard Forman: And I’m Howie Forman. We’re physicians and professors at Yale University, and we’re trying to get closer to the truth about health and healthcare. Today we have Professor Tim Westmoreland of Georgetown University joining us. But first, we always want to check in on whatever’s on your mind, Harlan. What’s the hot topic of the day?

Harlan Krumholz: You’re the one who told me what I should talk about today.

Howard Forman: Oh my God, because I think it’s the hot topic.

Harlan Krumholz: What’s on your mind?

Howard Forman: It’s on everybody’s mind.

Harlan Krumholz: Come on, what is it?

Howard Forman: It is whether Biden’s lapses during that debate are things that we should be concerned about and whether we can explain it from the healthcare point of view.

Harlan Krumholz: We are Health & Veritas, so it should be health and truth here. I know that you wanted me to first start talking about the paper that I... actually an article that I wrote with Jeff Sonnenfeld, assisted by Steven Tian, that was opining about what the cause of the problem was during the debate. Look, 50 million Americans, I’m sure almost all of our listeners had a chance to either see the debate or view some clips of the debate, and the point that I had in my discussions with Jeff, and let me just give Jeff credit.

Jeff was the one that said, could this have been a drug effect? And what I said to Jeff was, there was something that happened, and I think it’s almost like a clinical event. Look, he had altered mental status, in my belief, during that debate. It wasn’t just a slow start, it wasn’t just a bad performance, it wasn’t just like how Obama did against Romney.

Howard Forman: And the facial expression.

Harlan Krumholz: Look, he couldn’t string sentences together at the beginning of that debate, and then he said things that were just nonsense. And I had a professor one time in medical school, a neurologist, famous neurologist, who said to us, “Don’t normalize your patients.” What he meant by that was sometimes people would come to you with very overt symptoms and you’d sit there and go, “Well, I don’t know, people sometimes slur their speech, sometimes people drool, sometimes people walk with a limp, maybe it’s normal.” Your inclination is not to call it out as something abnormal. Not to say that this is something pathological. I mean, I saw this and I said, “This is different than what I’ve seen.” You may debate whether or not he’s lost a step or whether or not his cognitive function of baseline is different than it was a year ago, but this was different.

When he started off and said we beat Medicare, which made no sense at all.

Howard Forman: Still doesn’t.

Harlan Krumholz: At the end of that, he was struggling, and it was painful to watch. And so I said, “When I see this as a clinician, yeah, I agree.” The first thing that I think of is, it could be drug effect. And by the way, some of the common cold meds, especially things like Benadryl, can have remarkable effects, dramatic effects on people’s mental status, even temporally. Because you had to also reconcile the fact that this was transient. By the time you got to Waffle House or North Carolina, it had lifted, he was in a very different space. Now also people with dementia, this can happen. I mean, there’s lots of explanations—small strokes can cause this. I mean, there are lots of things I would tell you. If I saw somebody do that, I would think they needed to see a doctor.

I might send them to the emergency room because I would say, “Something just happened, and we need to figure out what it is, it could be metabolic, I don’t know what it is.” But, in the end, we wrote this article that suggested could this be meds? The White House didn’t come out and say until yesterday that they said he wasn’t on any meds, which also is kind of strange, because he’s got a cold! You mean you didn’t give him anything for that?

That seems odd. So that theory is away, but the main thing was, this seemed like an episode. And then Nancy Pelosi said essentially what we were saying, which was this seemed more like an episode than a general state, and it requires some explanation. Now he’s come out now and said, this is just jet lag. But it is true, I thought it’s a lot to put an 81 through. Two trips to Europe, a trip to California. Of course he is on Air Force One, but it’s a lot of travel. But it was a week…. He had a week of recovery.

Howard Forman: Look, they need, I think Nancy Pelosi’s phrase was best. Is this an episode or is it a condition? And if it’s an episode, you still deserve some way to explain it. And it’s not just travel that happened 10 days earlier. I wish him well. I don’t think that indicated that he can’t carry out the job he’s in right now. At least a single 90-minute period doesn’t make me think that, but I am very concerned and I think that we need transparency.

Harlan Krumholz: If you were a pilot, would you be happy if he was flying your plane?

Howard Forman: No.

Harlan Krumholz: I mean, this is the thing, and you and I have deep respect for him. We actually think this is the one of the most remarkable presidencies with regard to accomplishment because you and I share that view.

Howard Forman: Correct.

Harlan Krumholz: But I saw the part of the press conference yesterday too, and it’s a lot of stonewalling. It’s like, “let’s get back to his record.” And it’s not about that, it’s about, and they said, “Look, don’t make his presidency about 90 minutes.” But if you saw something like that—if you see something, say something.

Howard Forman: The way to make it not about 90 minutes is for them to be transparent and tell us everything that we need to know. And I really do sincerely hope that they clarify this in the very near future. And I personally, like you said, I wish him personally well, and I don’t think that this necessarily means that he can’t run or that he can’t function extremely well the next four and a half years. But this is a very important data point.

Harlan Krumholz: Yeah, and to make one more aside about this, of course, if you listen to former President Trump, he also didn’t make sense during the debate.

Howard Forman: No, but we’re used to it.

Harlan Krumholz: What was the thing about killing babies? I mean, I don’t know what he was talking about. The argument that he was making that people was somewhere in the United States are killing babies after they’re born. But again, that is his baseline. That’s baked in, right? I mean, that’s not a change. For Biden to be struggling to get out words and then to say things that didn’t make any sense.

Howard Forman: It was troubling, yep.

Harlan Krumholz: Hey, so let’s hope that gets clarified and we’ll see what happens. Look, we are living in dynamic times, but let’s get onto Tim Westmoreland and talk about the consequential SCOTUS decisions and a little bit about Tim’s background, which is quite interesting.

Howard Forman: Timothy Westmoreland is Professor Emeritus of Law at Georgetown University where he has been teaching about health law, health policy, bioethics, and importantly statutory interpretation since 2001. He also serves a senior scholar at the O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health. He kick-started his career at the House of Representatives working on healthcare policy matters for 15 years on the subcommittee on Health and the environment. He then worked for the Department of Health and Human Services in the Clinton administration as the director of the Medicaid program in the Healthcare Finance Administration, what we now know as the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Professor Westmoreland also advised the Kaiser Foundation on AIDS and worked with the Koop-Kessler Advisory Committee as a consultant on tobacco policy. He has won many awards for his distinguished career in public service. He received the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Investigator Award in Health Policy Research in 2002, and he was also selected to receive the award of courage from the American Foundation for AIDS Research, or amfAR, that same year.

He’s also published many articles about public health and health law and national media outlets. He graduated from Duke with his bachelor’s and received his law degree from Yale Law School. And so I want to start off, because I think today we’re going to spend a lot of time talking about statutory interpretation and specifically what the Supreme Court rulings are, but we’d be remiss not to talk about your role working for Henry Waxman on AIDS policy from times when we did not even know AIDS existed, that you were elevating this to the nation’s consciousness and being able to bring light during a time when the Reagan administration was not even noticing the disease. And if you could just comment how you got involved in that and how that transpired.

Timothy Westmoreland: Well, first thank you for the introduction and thank you for the invitation to be here. When I was working for the Waxman staff, I was the public health staff person; that was my portfolio, NIH, CDC and FDA issues. And as part of that, I visited the Centers for Disease Control at the beginning of the Reagan administration and went around and met people in the various different program offices. And I met a guy whom I think both of you know, named Jim Curran, who was at that point a CDC sexually transmitted infections investigator. He’s now the dean or maybe the retired dean of the Emory School of Public Health. And he was working on, as part of this sexually transmitted infections, working on this outbreak of this form of pneumonia among gay men in Los Angeles, which was my chairman’s district.

And I said, if there’s something that we can do to be helpful, I would like to be, I’m sure Mr. Waxman would want to be helpful. And Jim Curran said, “No. No. The best—I am just barely getting the confidence of the gay community in Los Angeles. The last thing I need is to bring politicians and congresspeople into this discussion. So thanks but no thanks.” And I said, “Well, let me know if it turns out there’s something I can be doing.” And about a year later I got a call from him saying, “I think I have their confidence now, and I think that we need to call some attention to this.”

And so we had a hearing in Los Angeles at the Gay and Lesbian Community Services Center and started that discussion and started with public health officials saying what they thought needed to be done, even though the Reagan budget officials were saying, “No, we’ve got everything. We don’t need anything more.” And from that, I ended up doing about 35 hearings over the course of time on AIDS and HIV. And the Congress produced some legislation that arose from those hearings.

Harlan Krumholz: Tim, you’ve navigated the halls of power and have worked very closely with Ruth Katz, who we were privileged to have on the program recently.

Timothy Westmoreland: She is my best friend.

Harlan Krumholz: We love Ruth, and I know you guys are so close, and you guys were such a formidable team in getting things done when you were working with Waxman. She reflects often on the changing culture of the Hill, the ways in which things have gotten more difficult. I just wonder before we launch into... because we really want to hear your views on what’s going on with SCOTUS, but I just wonder your own reflections on politics, where we are today, and whether there’s any chance to reclaim the kind of spirit that you guys had and that your colleagues had to try to get things done. I mean, we do see things passed, but there’s a very different feel on the Hill now than there was then.

Timothy Westmoreland: There is. During the time that I was describing just now to you, and when Ruth and I worked there together, I used to say that working on the Hill was like living in a dorm that you went off to different classes during the day, but you would meet up and you’d be friendly. I actually went to the birthday parties for the children of the Republican staff. I went to a wedding of my Republican counterpart. We were friendly. We disagreed and we argued, but we were friendly. And these days, I went back to work on the Affordable Care Act during the Obama administration. I went back to the Hill, and it’s scorched earth. People didn’t even know each other’s names; people wouldn’t return each other’s phone calls. And I find it very hard to imagine how the dorm-like atmosphere of being a staff person is going to return when people are as hostile and dismissive and downright abusive as they are to each other these days.

To make the Congress work, people have to be able to sit in a room and come to compromise agreements. I used to sit down with my Republican counterpart and say, I can give on one, three, and five if you can give on two, four, and six, and we can come to a compromise. These days, I don’t think we could even agree on what was on the list! So, it’s so harsh and so angry and so focused on sound bites. Whereas Mr. Waxman, at one point in a profile that was done on him, pointed out, and I think it’s very true, it’s amazing how much work you can get done in the Congress if you don’t care who gets credit for it. And he was oftentimes behind the scenes or working to give a junior member, sometimes as a Republican Party, credit for getting something done. And consequently, we were able to come to more agreements. I don’t see anybody actually even giving people of their own party credit these days, and I certainly don’t see that people are working collaboratively to be able to come to compromise and make important things happen.

Howard Forman: You really understand both the law as well as health law specifically. We have had a very consequential Supreme Court term that ended just this week, on July 1st. And I think, suffice it to say that there are so many rulings that are non-healthcare that are consequential, but even in healthcare there are big things. And we had Reshma Ramachandran on earlier this year to talk about what her thoughts about why Chevron mattered, but she spoke to it from a physician point of view and a public policy point of view. You have been teaching Chevron for decades now. Can you speak to why this concept, what did Chevron deference mean, and why does it matter?

Timothy Westmoreland: Okay, let’s do the very basics, and it’ll only take me two minutes to do this, but I’ll do the very basics. Congress writes statutes. Often administrative agencies have to apply the statutes. And in doing so, the agencies oftentimes run into gaps and ambiguities about what the statute says and agencies make a decision about what the best interpretation of that ambiguity is or how to fill the gap. Usually that’s in the form of a regulation, but there can be other forms of interpretation too. And regulations have to go through a process, it’s quite formal. And if someone is affected by an agency regulation and they disagree with the interpretation of the agency, they say that the statute says something else, they can challenge that in court and they’ve been able to challenge it all along. So, before 1984, a court would review the statute and review the arguments about how best to interpret it, and they’d consider all the arguments including those from the agency, and the court would treat the agency’s view as if it were an expert opinion. The view of someone who had a lot of experience in the area.

But the court said, and this was the Supreme Court doctrine at the time, that the court would make up its own mind about what the statute means among all the various possibilities. The Supreme Court put that rule in place, which you’re going to hear more of now, called Skidmore, in 1944, so it’s been around for a long time. But 40 years later, the Supreme Court established a new decision of Chevron v. NRDC in a case involving air pollution, and they created two steps. The first step is for the court to decide whether the Congress’s intention really was unclear, and if they say, no, that “We see what it means using the usual way of interpreting,” then the court will enforce that, no matter what the agency said. If the court says, “It’s really ambiguous, we can’t tell what the Congress’s intent was,” then the court would then look at what the agency’s interpretation was and, unless the agency did something truly arbitrary or unreasonable, the court would defer to the agency, and that’s what we’re all talking about, Chevron deference. This should not...

Howard Forman: Just to... sorry to interrupt. NRDC, when you said “Chevron v. NRDC.” NRDC was whom or what?

Timothy Westmoreland: National Resources Defense Council. It was an environmental case about the Clean Air Act.

Howard Forman: Got it.

Timothy Westmoreland: But the rule that came out of Chevron isn’t limited to clean air or environmental. It’s been applied to anything having to do with agencies. But I want to emphasize that it didn’t mean that the agency always won. The courts have said a number of times that the agency just got it wrong. It’s step one, and they didn’t even get to the question of whether to defer or not. But if they got to question two, “we think it is unclear, let’s look at, see what other interpretations,” most of the time the agency would win if the court got to that level. And that Chevron rule has become a really big deal. It’s a foundational piece of American law. I’ve seen it estimated that Chevron has been cited in federal court opinions 18,000 times.

I’ve seen it estimated that Chevron was the turning point in more than 200 cases in the Supreme Court over the last 40 years. It’s become the fulcrum of administrative law from FDA to CMS, to the Securities and Exchange Commission to the Defense Department, it’s everyplace. And in addition to those arising in all those cases, I want to say it also has had a calming effect about litigation. A lot of cases aren’t brought at all because lawyers know that the agency is likely to get deference, and so they go along with the regulation and the courts don’t have to deal with the question.

Howard Forman: And just a quick follow-up to that, bringing it back to healthcare right now, public health law, CMS, CDC, FDA…. What is the immediate implication for this?

Timothy Westmoreland: For the Chevron decision or for—

Howard Forman: For the reversal of it.

Timothy Westmoreland: Okay, well, Chevron is gone, gone, gone. Now we’re back to Skidmore again: the court will decide. What it means for this is that in each instance, the court is going to make its own judgment, no matter how technical, no matter how obscure, no matter how unanticipated the question might have been. I used to tell my students that, ask them what the Congress meant about the internet when they wrote the Telecom Act of, I think it was 1934. What did they mean? So now, the Court is, it’s a power grab by the court to say, we’re going to make up our mind. And every one of these regulations and even administrative decisions, like drug approvals for FDA or fee schedules for CMS, every one of those is going to be, somebody... when an agency makes a decision, somebody’s unhappy with it. Somebody thinks they should have been paid more, somebody thinks the drug should have been approved, whatever, and now they can sue and say, “Well, the agency’s interpretation was wrong, let’s take it to the court and show them.”

Every single one of these actions is up for grabs. The court says, “Well, if they’re not happy with it, the Congress can write a new law.” But the question—as we were just discussing, the Congress isn’t doing very well these days. I think that the courts are going to be in charge. Even under Chevron, even with regular statutory interpretation, I’ve told my students over the years that this is Schrödinger’s lawsuit. The meaning of the law is both alive and dead at the same time. The meaning of the law is A and B at the same time until a court says what it is, and under Chevron, we could say, well, we’ve got a pretty good idea that it’s going to be A, because the agency said that, and it’s just not good for, I mean, industry...

Harlan Krumholz: Here’s what I’m trying to figure out, Tim, is, isn’t this going to clog up the courts, one, two...

Timothy Westmoreland: Oh, absolutely.

Harlan Krumholz: Does this mean... So just go back to FDA, because I mean, I’ve read what they’ve been writing about this, but I’m still, even as deep as I am in this, confused and I know you explain things better, as anyone I’ve seen, comes to this kind of stuff.

Timothy Westmoreland: You’re very kind.

Harlan Krumholz: Well, so the FDA, for example, is making interpretations of statutory law all the time. I mean, every single day they’re making interpretations of it. So in the past, again, with this deference, people would say, well, the FDA’s entitled to make that; they’ve got the expertise. And now every time someone doesn’t like something that the FDA says, they can basically now with some prospect of being able to overturn depending on the jurisdiction and the judge and the judge’s biases, be able to actually dictate to what’s going on. And here’s my major point I think for everyone, not just they say this is a triumph for the conservatives, but what business likes is predictability.

They want to be able to know what they can rely on as they’re making investments. And now it seems to me like they’ve just ratcheted up the unpredictability of the interpretation statutory law. And like you said, the chance that Congress is going to get more specific on these laws is, they can’t agree on the broadest of things. Getting back to your first issue about how Congress gets together, they can’t agree on the broadest swaths of thematic issues, let alone be able to get down where they’re going to take the pencil and make these kind of highly specific issues. So, I think this is going to create havoc, but am I wrong to be concerned?

Timothy Westmoreland: No. You’re right to be concerned. And no clear law means confusion for everybody. And industry likes clear standards. They like weaker standards in many cases, but they like clear and consumers don’t like ambiguity either, they like clear information and protection from unnecessary…. But now, in this instance, one of the things that I’ve seen people discussing this week has been that the statute for the Food and Drug Administration says that the agency is supposed to look at well-designed tests to decide whether something is safe and effective.

But the definition of well-designed tests isn’t in the statute. The FDA has to decide what is a well-designed test. And, in that instance, I suppose it means that somebody could show up and say, “I have a drug here that I’ve studied in four people and nobody died. Approve it—it is safe and effective. I looked at them for two weeks, and that’s a well-designed test.” I would hope that any court would look at that even without Chevron and say, “Oh, don’t be ridiculous,” but you can’t be sure. And it means, what you alluded to, each district court can have its own opinion of what’s a well-designed test and we could end up with 50.

Harlan Krumholz: Isn’t the court supposed to be considering feasibility? Like what accrues as a result of their decision? I mean, that’s a puzzle...

Timothy Westmoreland: No, Justice Jackson says in her dissent, this is going to create a tsunami of litigation. It’s just going to be overwhelming. And it also means...

Harlan Krumholz: So this is on the immunity case, they go, we don’t want litigation, so that’s why we’re going to decide this. Here they’re saying, well, what the heck?

Timothy Westmoreland: Well, don’t get me started on the immunity case. But what I cannot imagine is how many pieces of litigation they’re going to be arising just because somebody doesn’t like an individual decision made by an agency and because of another case that came down—help me, Howie—Corner Post, is that what it is?

Howard Forman: Corner Post, yep.

Timothy Westmoreland: Corner Post. That decision said over is not over, you can reopen things on agency regulation. So that means that they can go back and say, well, this test wasn’t well designed, or that rate under Medicare was not fair, or this standard for 10b-5 disclosure in the SEC isn’t right. So Harlan, it’s not just for new things that everything is up for grabs. To some extent, the combination of those two cases means that for old things, everything’s up grabs. I know that a lot of conservatives have called for the end of the administrative state, but did they mean to get rid of it all at once? It just seems like it’s going to be anarchy for a while. Anarchy for everyone who can afford a really good lawyer.

Howard Forman: I want to make sure we get one last thing and before we have to go, could you give us a little bit on mifepristone and whether the Supreme Court truly punted on that and what it might mean now that Chevron has been overturned?

Timothy Westmoreland: Well, they dismissed the case for reasons that are altogether unrelated to the issue of abortion. They just said that the people who are bringing the litigation weren’t harmed by the approval of the drug, so they shouldn’t be here. I mean, they even quote an old Scalia line: “What’s it to you?” These doctors shouldn’t have been in court, so they just dismissed it. But it doesn’t mean that somebody can’t come back under the Chevron doctrine or the reversal of Chevron and now ask that the court revisit it because they might have standing to sue.

Or more important even than that is, that a future administration can change the FDA approval of the drug for an altogether different reason and say, “Oops, we don’t think that was a well-designed test” or “Oops, we think this is not effective.” So, we’ve got coming from both directions, then the administration could change the approval or another set of litigants who can say that they were harmed in some way can come into court and prove it. But in this case, it’s a total punt. They didn’t decide anything substantive.

Howard Forman: I just want to honestly say you have been an amazing public servant, a professor, a policy advisor. You’ve come to Yale many times and contributed to our courses here. And most of all, you’ve been one of my best friends, and I just thank you for coming and joining us on the podcast.

Timothy Westmoreland: Well, it was my pleasure.

Harlan Krumholz: Yeah, Tim, it’s great having you. Thanks so much.

Timothy Westmoreland: It was my pleasure. I’m happy to be here. Thanks for the invitation, and good to see you guys again. Enjoy the summer.

Harlan Krumholz: Howie. That was great. And look, you’ve got great friends, good friends with Tim. He’s a remarkable individual, sort of an unsung hero, right? He is just contributed so much.

Howard Forman: He is amazing.

Harlan Krumholz: Most people don’t know his name, but he’s done so much.

Howard Forman: He has been an important person in my life, and I’m really glad we got to hear from him here.

Harlan Krumholz: That’s great. So let’s hear... What I said was, my preference now at the end of the program was to hear your views on some of these consequential decisions and their implications for health policy.

Howard Forman: So I’m going to run through them, even though he talked about Chevron doctrine. I’m going to give you a very quick brief on that and I’m going to cover each of what I think are the consequential rulings. But very briefly, and so I’m not a lawyer. I don’t pretend to be a lawyer, but...

Harlan Krumholz: No, but you’re a health policy expert.

Howard Forman: I love the Supreme Court. This season every year, I am very attentive to this. So, I’ll just remind our listeners what Chevron doctrine basically said is, if Congress has not directly addressed the question at the center of its dispute, a court was required to uphold the agency’s interpretation—this is what Tim was getting at—of the statute as long as it was reasonable.

Harlan Krumholz: Can I ask you one question about this, I’m confused about? A court needs to uphold it. Does that mean in response to someone filing something?

Howard Forman: Yes.

Harlan Krumholz: So they won’t automatically get involved.

Howard Forman: But at a lower court. At a very, at a very low court, you could file something and they would say, “Look, Chevron doctrine dictates that you have not met this two-step test and therefore we’re throwing it out. It’s not even going to court.”

Harlan Krumholz: I see.

Howard Forman: So that’s how it starts each time, in my understanding of the law. And so now you have these two rulings combined as one Relentless v. Commerce and Loper v. Raimondo. And the Court ruled 6–3 and 6–2. So a very split decision with the conservative justices in the majority and the liberal justices, so to speak, in the minority in the dissent that Chevron doctrine is unworkable and therefore it’s overturned and going forward, the proper place for adjudicating legislative vagueness regarding regulations is back in the courts rather than in the hands of the regulatory experts. We talked about what that may mean, and I’ll point our listeners to a paper by Sahil Agrawal along with our own Reshma Ramachandran and Joe Ross in JAMA in March—we’ll have it in the show notes—that really does a nice job explaining what this means for healthcare and it means a lot.

So, that’s number one. I think that is the most important thing in the term. Last week we briefly covered Murthy v. Missouri. That was the free speech case mostly rested on whether the federal government was encroaching on First Amendment rights of social media companies and their customers. And here the court actually didn’t rule on the substance but felt that the plaintiffs did not have standing, meaning they had not shown that they were harmed by the action. So this is not quite a healthcare case, and it’s not even really a free speech case, it’s a standing case. And this nicely was Amy Coney Barrett writing for the majority. Alito, Thomas, and Gorsuch dissented, but that’s punted, we haven’t really made any free speech decisions here, that was on standing. The people who brought the case didn’t really have a right to bring the case. The next case, which is what I asked him at briefly at the end, is FDA v. Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine case, which is the mifepristone case.

And here again, the Supreme Court dismissed the case on standing, sending it back to the lower courts where it might continue; unlikely, but might continue. This was a unanimous decision, but on standing. Standing meaning that the people who brought the case didn’t actually have a claim in front of the court. And with the reversal of the Chevron doctrine and the ruling in Corner Post, which extended the statute of limitation to file a claim of harm, this is going to come back to the court. And I do fear that in a Republican administration in particular, you’ll see this undone by executive action. And even without that, you may see it undone by court action. So mifepristone, which is 60% of all abortions, remains at risk. And then the other big case about abortion was Moyle v. the United States and Idaho v. the United States, which is where the federal rule called EMTALA, the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act, which compels hospitals to that receive Medicare dollars to provide emergency triage, stabilization, and disposition to acutely ill patients, including those in labor.

That law comes into conflict with the Idaho law, which basically bans abortion completely except to save the life of the mother. And the issue here was, the question is, is it only to save the life of the mother? What if the mother’s life is not really in danger but her fertility becomes in danger or she’s going to become septic or something else? And so here again, the court basically dismissed this case on being “improvidently granted,” which is their way of saying that when they first consider the briefing documents that came to the court, they thought there was a case there.

And then when they listened to the case, they realized there is no case there. So they didn’t really rule on the case, they just said we shouldn’t have listened to it to begin with, that too may come back. And then the last thing I want to mention is that we didn’t talk about other more marginal healthcare cases, but homelessness as a crime is another case that was ruled on. And additional monies for certain tribal nations for their health services were also ruled on. We already know that next, in the next court session, next year, we’re going to learn more about transgender care in adolescents, and we’re going to learn more about the limits of FDA authority for e-cigarettes and their distribution.

Harlan Krumholz: So there’s a lot there. That was a wonderful summary. Let me just go back to one thing. I just want to make sure I understand your point of view on this. So, when I see something like the Chevron case, I think, it was natural people on the left were up in arms and people on the right were cheering, not uniformly, but on average. But doesn’t it matter who’s in the executive office? Because won’t the Democrats be happy about this if Trump is elected? Because now he will have less discretion, his federal agencies will have less discretion than they might have had otherwise. So isn’t...

Howard Forman: The original...

Harlan Krumholz: Whoever we were cheering for now, it’s like it depends on who’s in the office, right?

Howard Forman: Right. So, the original Chevron case was brought by Anne Gorsuch, the mother of the Supreme Court Justice, who ruled on it now, who actually I think wrote the opinion and she was working for the EPA at the time and they wanted to remove regulations. And the Chevron case came into play, gave her the latitude to do that. And so I think you’re right about it, but I think it also just puts the agencies into a position of almost paralysis. They have to hire more lawyers just to make sure that as they write regulations and as they work with Congress to write statute, it now has a higher bar to meet.

Harlan Krumholz: It just seemed a little unrealistic to me in the sense that if you do think that the agencies have some expertise, you’re not really allowing them to express it as much.

Howard Forman: Exactly.

Harlan Krumholz: You’ve lowered the agility of the federal government.

Howard Forman: That’s right.

Harlan Krumholz: And look... Go ahead.

Howard Forman: That’s the point that you were making at the beginning is that right now the conservatives in government are not offended by paralyzing the bureaucracy because they actually see that as part of the mission. I don’t mean all of them, but certainly some of them really believe paralyzing the bureaucracy is not a bad thing, and if this does that—not a bad thing.

Harlan Krumholz: But I can see that on an activist agenda. But when you’re talking about the FDA, there’s a lot of these calls and...

Howard Forman: And oh my God, every...

Harlan Krumholz: Look, these are “balls and strikes” that are being called here, and now they’re going to potentially be, each one thrown into question.

Howard Forman: Absolutely. They could sue over the recent Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy drug approval, there’s all sorts of things they could sue over that become much more difficult under these circumstances.

Harlan Krumholz: Great. Okay. Well, thanks so much, guy, that’s amazing. You’ve been listening to Health & Veritas with Harlan Krumholz and Howie Forman.

Howard Forman: So how did we do? To give us your feedback or to keep the conversation going, you can email us at health.veritas@yale.edu or follow us on LinkedIn, Threads, or Twitter. And I want to just add that this week is Independence Day, not only for the United States but for the Yale School of Public Health, which as of July 1st is a fully independent school in Yale University, and Megan Ranney is the inaugural dean of that fully independent school. So kudos to them, congratulations and Happy Independence Day.

Harlan Krumholz: Oh my gosh, Howie, I’m so glad you reminded me about that. And just to make a big point, anyone who hasn’t had a chance to listen to Megan Ranney, who we had on this program, is missing a treat because she is vibrant, visionary, it brought a ton of energy. We’ve had good leaders before, I don’t want to in any way diminish their contributions, but I’m thrilled to have her in the leadership role and as an independent school public health, everyone, keep your eyes on this school because things will be happening.

Howard Forman: We agree.

Harlan Krumholz: So we want to hear your feedback, questions, experiences on our topics, please do so. And also by rating us and reviewing us, it helps more people find us. So just know we’re eager to hear from you.

Howard Forman: And we try to respond to your questions on whatever social media you put them on, so thank you for that. If you have questions about the MBA for Executives program at the Yale School of Management, reach out via email for more information or check out our website at som.yale.edu/emba.

Harlan Krumholz: Health & Veritas is produced of the Yale School of Management and the Yale School of the newly independent Yale School of Public Health. Thanks to our researchers, Ines Gilles and Sophia Stumpf, and to our producer, Miranda Shafer, recently married. She looks so happy. It’s such a joyous....

Howard Forman: Really happy to have all of them. They’re a great team.

Harlan Krumholz: Yeah. Talk to you soon, Howie.

Howard Forman: Thanks very much, Harlan. Talk to you soon. Happy Independence Day to all listeners.