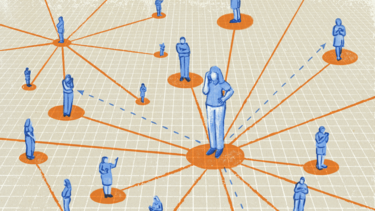

Your Friends Have More Friends Than You—and That’s a Good Thing for Marketers and Public Health Officials

In a new study, Professor Vineet Kumar and his co-authors offer two ways to seed interventions in social networks based on the “friendship paradox.”

If you’ve ever been bothered by the feeling that your friends have more robust social lives than you do, you’re not alone. Lots of people feel that way, and, mostly, they—and you—are right. For decades, social scientists have recognized what’s known as the friendship paradox, which says that on average, the friends of any given individual have more friends than the individual does.

But even if the phenomenon isn’t good for your self-esteem, it turns out, it is very good for maximizing the effectiveness of limited vaccine supply or raising awareness about a new product or informing people about misinformation.

New research by Yale SOM’s Vineet Kumar explores how to identify highly connected network nodes (or individuals) without knowing the entire network. Together with his co-authors, he examines the mathematical principles underlying the friendship paradox and presents two methods—including a novel approach—to leverage this principle for seeding interventions in online and real-world social networks. These interventions can benefit public health, political, or marketing campaigns.

Kumar, an associate professor of marketing, studies technology and its implications for business and society. He has studied consumer choices and firm strategies in digital markets, as well as in user-to-user networks.

Using Kumar’s approach is more effective than other methods of seeding networking interventions “if we’re trying to stop an infection from becoming an epidemic, or, in the case of a marketing campaign, to do the opposite,” he says.

The research investigates the principle of inversity, which measures whether two connected network nodes are similar or dissimilar in their connectedness (measured by the number of friends). Based on this concept, Kumar and his co-authors—Scott Feld of Purdue University, who wrote an earlier paper on the friendship paradox in 1991, and David Krackhardt of Carnegie Mellon University—investigate two methods for seeding interventions.

One method, the ego-based strategy, involves asking a random person in the network to provide the contact of one of their friends, who would then be chosen as the “seed” or target of the intervention. Depending on the application, the seed could be selected to receive a vaccination or given information to share widely. This method has been used in the past, but its effectiveness has not been shown mathematically and empirically.

The second method, the alter-based strategy, is apparently novel. “We are the first to propose it, as far as we can see,” Kumar says. In the alter-based strategy, a random person in the network is asked to provide contact information for multiple friends based on any chosen percentage or proportion. For instance, if the rate is 50%, the person would flip a coin for each friend to determine whether to provide their contact information. The selected friends would then be used to seed the intervention.

Both the ego-based (also called local friend) strategy and alter-based strategy perform better than existing methods, including choosing someone at random to seed an intervention or relying on network leaders. For instance, in an epidemic model, immunizing about 25% of a network using either of the two strategies would be sufficient to prevent an epidemic. In contrast, a random intervention would require immunizing about 50% of the network.

A major advantage of the methods analyzed in Kumar’s paper is their focus on privacy sensitivity. Most other interventions require extensive knowledge about a network’s structure and its members to improve upon the random seed intervention strategy. “I don’t know about you, but I wouldn’t necessarily feel comfortable sharing all my friends’ information with a company or researcher,” Kumar says. “But if they ask me for one friend, I might be more likely to share.”

Kumar points out that there are other factors to consider when planning how to seed an intervention, including, in the case of public health campaigns, equity-based factors. But the friendship paradox is a very relevant consideration for performance, he adds.

“The idea applies very broadly to any network and application,” he explains. “The people that are more popular”—and therefore more effective in seeding interventions—"are more likely to be reached using the friendship paradox.”

Kumar has been investigating the use of these methods in additional domains. In a paper with his colleague K. Sudhir, “Can Random Friends Seed More Buzz and Adoption?”, he empirically evaluated whether using the friendship paradox could improve upon a previous effort to use opinion leaders to spread the word about microfinance through villages in rural India (in short, it could).

The findings have implications for a variety of fields, including marketing, public health, and even politics, Kumar says. If someone want to see how far misinformation about an issue or candidate has spread in a given network, for instance, they could use the alter- or ego-based friendship paradox strategies to do so.

“The thing that I’m really happy about is that these are simple, privacy-sensitive interventions that can easily be deployed across applications,” Kumar says.