Why Connecticut’s Investments Are Underperforming

Yale SOM’s Jeffrey Sonnenfeld and Steven Tian and their team found that Connecticut’s return on its pension fund investments is among the worst in the nation. Their analysis of all 50 states offers some avenues for improvement.

The Connecticut State Capitol in Hartford.

This commentary originally appeared in the Connecticut Post.

We have previously chronicled how Connecticut’s economic development momentum, public spirit, and business climate are all improving. Nonetheless, Connecticut is still the second highest-taxed population in the nation.

One year ago, Governor Ned Lamont signed a budget which included the largest tax cut in Connecticut history, and this legislative session, Lamont proposed the first income tax cut since the state’s introduction of income tax in 1991. But there is another simple way to dramatically lower Connecticut’s taxes and improve Connecticut’s fiscal standing and business climate. If Connecticut had even average annual investment performance from its underwhelming pension funds, our tax burden would dramatically decrease.

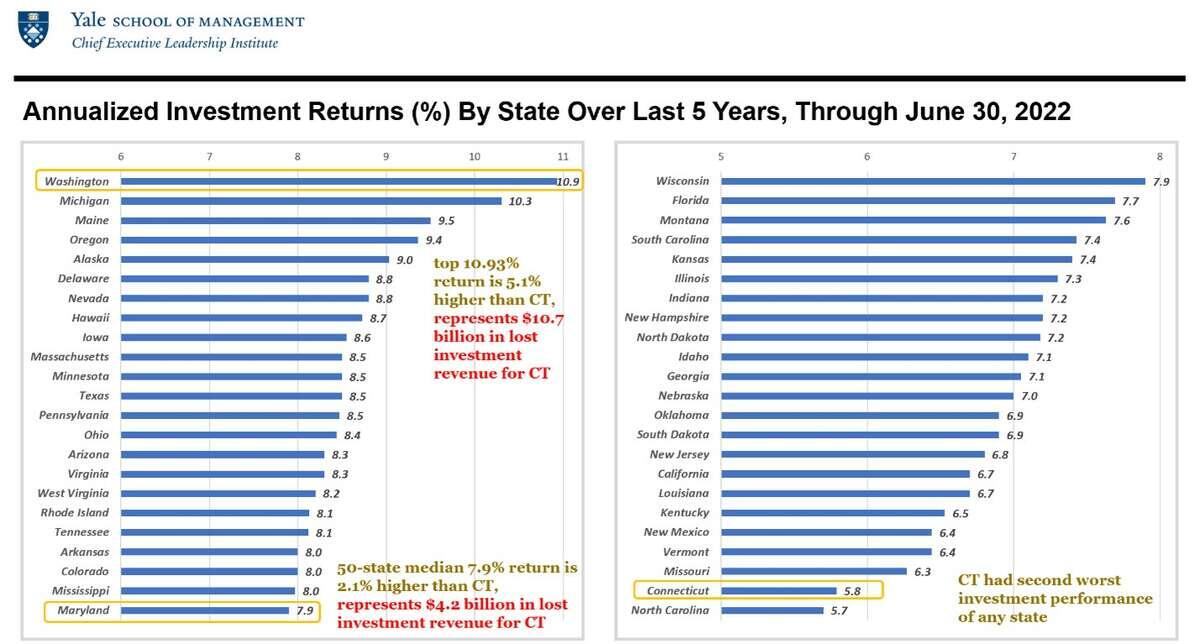

While the legislature battles over thousands of dollars or even millions on needed expenditures, billions of dollars were lost on terrible investments—investment errors that 49 other states somehow avoided. Connecticut’s previous treasurers provided this state, consistently, with one of the single worst investment track records of all 50 states, as our Yale research team found through an original, comparative 50-state analysis of state pension fund investment performance.

With $40 billion in assets—largely the pooled retirement savings of the state’s hardworking teachers, firefighters and public employees—if Connecticut’s investments had yielded just the median returns of all 50 states, the past five years, we would have had $5 billion more and be able to cut taxes by 50 percent instead of 0.5 percent. Connecticut would have reaped a whopping $27 billion more over the last decade—practically enough to fully fund Connecticut’s pension obligations while simultaneously dramatically reducing taxes.

Lamont will have already steered roughly $8 billion from the state’s budgetary surpluses to plug the hole by the end of this year, including $4.1 billion last year alone—as supplemental contributions on top of the $3 billion plus in annual, mandatory payments.

This is not the consequence of political partisanship, union voices, reckless spending or government bloat—the causes normally attributed to the state’s chronically underfunded pension obligations. Prudent efficient public administration is great, but this is a different problem—incompetent investment for decades.

Our study found that across all 50 states, investment performance has nothing to do with divisive red herrings such as political party, ideology, state size, or geography. Red states and blue states, Sun Belt and Rust Belt, big states and small states, vary on the quality of their performance independent of labels. For example, the 10 best states over the past decade include Washington, Michigan, Minnesota, Arkansas, Oregon, Massachusetts, Ohio, Colorado, and West Virginia.

Connecticut’s underperformance is also not based upon support for local Connecticut-based asset managers or minority owned/led asset managers, as we just have among the worst performing asset managers regardless of how they are classified.

Rather than using larger, more well-known fund managers as other states do, there are cases where we are invested in funds where Connecticut is the single largest client—sometimes substantively the only client, all while Connecticut pays high fees, with some obscure asset managers individually earning more than the entire state’s cabinet combined.

We would recommend five basic steps based on our comparative 50-state analysis.

- Careful and accountable asset manager selection—picking top-tier asset managers and dropping worst performers. Like all state pension funds, virtually all of Connecticut’s assets are farmed out to external investment managers who then direct investments on behalf of Connecticut’s firefighters, teachers, and public employees. Needless to say, we should focus on top-tier, blue-chip funds with proven track records of success—and conversely, we should terminate relationships to the worst asset managers.

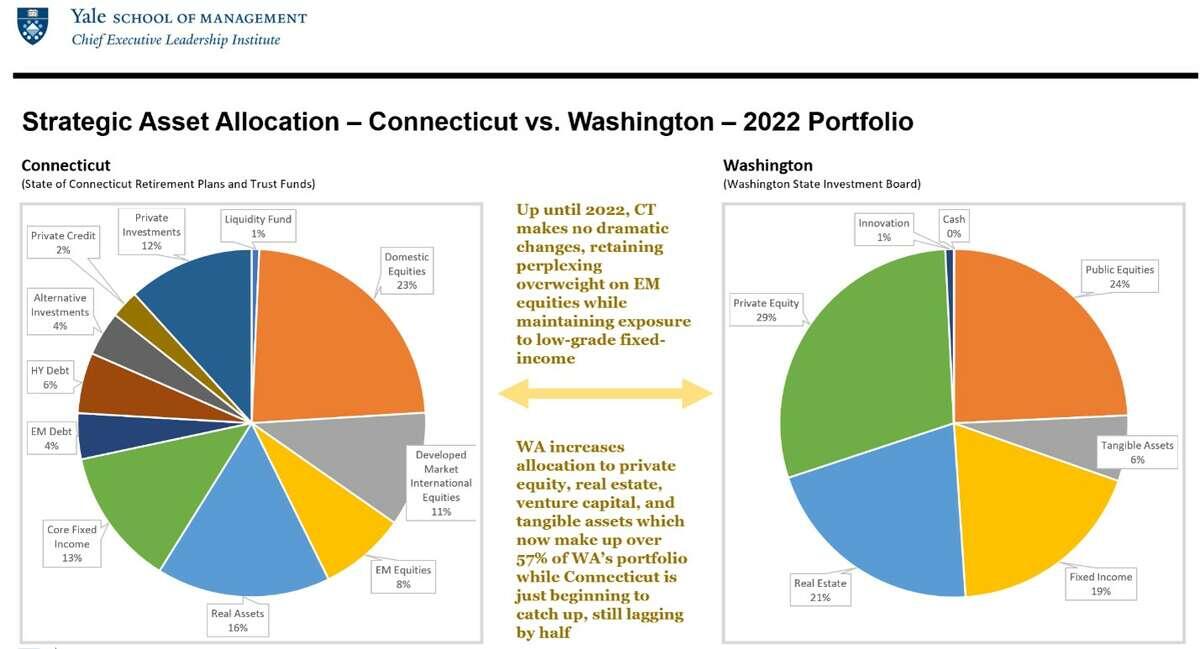

- Change the asset mix. Connecticut has made some poor and costly decisions over the past decade—many of which are now smartly being unwound by current leadership. Connecticut’s public equities (stocks) portfolio was massively overweight emerging markets and underweight U.S. equities—meaning Connecticut largely missed out on the strong bull market of U.S. stocks over the last decade.

- Consider shifting into more low-cost index funds. Unfortunately, Connecticut’s highly compensated professional asset managers got dramatically worse returns for the state’s teachers, firefighters and public employees than if these individuals had just invested their savings themselves. As we found, over the last decade, a generic 60/40 portfolio (meaning 60% stocks, 40% bonds) outperformed Connecticut’s by over 1 percent annually. The compound interest on $40 billion is a powerful force, amounting to more than an extra $4 billion. A generic 70/30 would have done even better, outperforming Connecticut by 2.5 percent annually over the last decade.

- Increase the transparency of performance. While the treasurer’s office commendably posts aggregate performance to its website on a monthly basis, releasing semi-annual manager-by-manager breakdowns of performance would help fortify accountability and transparency. Furthermore, while some may say the asset management fees we have been paying for terrible performance are, at least, average for the 50 states, that is is not the case, because these manager fees must be calculated to the assets which are actually managed and not on the entire $40 billion fund, which includes index funds or investments with no management fees. While taking strides in the right direction, they postings are detailed impenetrably dense “info packets.” As Louis Brandeis said, “sunlight is the best disinfectant.”

- Enhance the talent recruitment into the treasurer’s team. While we have had the same treasurer for 20 of the past 25 years, access to top-tier talent is a strong focus for new Treasurer Erick Russell, who is also simultaneously dealing with external calls to reduce headcount or funding for his office. Connecticut recently churned through eight chief investment officers and four interim CIOs. By contrast, all the top 10 performing states have long-tenured CIOs—but there seems to be zero correlation between CIO salary and investment performance.

It is past time that we fix Connecticut’s solvable investment woes. As Benjamin Franklin advised in his 1758 essay entitled “The Way to Wealth,” “An investment in knowledge always pays the best interest.” We need some investment managers who know what they are doing or at least who can provide us with average if not top performance.