The Jack Welch That I Knew

Jack Welch, the legendary CEO of GE, died on March 1. Yale SOM leadership expert Jeffrey Sonnenfeld, who knew him for decades, writes that Welch was flawed but brilliant, an innovator and icon of industrial imagination.

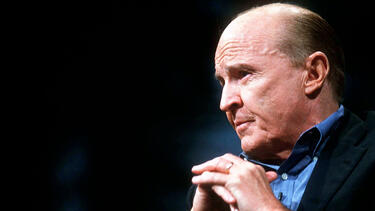

Erik Freeland/Corbis via Getty Images

This article originally appeared in Chief Executive.

I knew Jack Welch personally for 40 years, having brought him to my MBA classes, taught for him at GE, visited with him at his office, and shared many meals over the decades. Jack was brilliant, with historic contributions to global commerce, and also imperfect; like all of us, he had his flaws.

But the business world is changed and better because of him. He was, without doubt, an icon of industrial imagination.

While we should not deify him—like Thomas Edison and Steve Jobs, he was highly effective in his self-promotion—he was a unique titan of industry and a loyal friend and dedicated patriot. “He was a compassionate competitor,” said Ken Langone, a long-term GE board member. “He understood a pat on the back for great triumphs but also always reached out to those who were at the end of their GE career. They’d leave feeling that they just got a promotion as he celebrated them and matched them with headhunters for new opportunities.”

An enemy of rigid structures and mediocrity, Welch was a champion of meritocracy. The personable, energetic Welch always encouraged people to speak their minds openly in meetings, never shooting messengers with bad news, and not standing on ceremony. He frequently made surprise tours of GE facilities. The son of a railroad conductor, he did not have a fancy pedigree himself and did not overvalue social standing, club membership, or educational credentials. He did not stand on rigid traditions of any sort, insisting that everyone refer to him simply as “Jack.” He strived for all his businesses to be either first or second in their industries.

General Electric lost 21% of its market value under Welch’s revered predecessor, Reginald Jones. Welch reversed that. He kept GE from going the way of fellow industrial titans like Westinghouse, U.S. Steel, Woolworth, and Litton Industries. Welch always was curious, asking questions with a rare facility to move between macro-strategic and micro-operational levels of analysis.

He inherited a business worth $14 billion; 20 years later, it was worth $400 billion. Nevertheless, he was not the leading stock market performer of his generation, despite massive press to the contrary. He proudly celebrated his 2,504% total shareholder returns between 1984 until he stepped down in 2001 compared to the S&P 500’s total shareholder return of 1,042% over those years. However, in the exact same period, the far-more-humble Reuben Mark of Colgate-Palmolive produced 3,372% total shareholder return. If you fold in the durability of his GE legacy, the total shareholder return of GE from 1984 through last year was 745% vs 3,385% for the S&P 500 and 10,254% for Colgate. During Welch’s last year on the job, GE stock fell 24%.

Part of his legacy was his leadership development commitment. Welch was not a snob and would talk with anyone, to learn something new or discover rising talent. His renowned Series C meetings every 90 days were very tough, periodic talent reviews which he cared about almost as much as business-unit performance. He taught many GE Crotonville management classes himself. His progeny included a who’s who of American leadership, including Jeff Immelt of GE, Bob Nardelli of Chrysler, Jim McNerney of Boeing, Dave Cote of Honeywell, Jeff Zucker of CNN, and Davis Zaslav of Discovery. He was blunt and direct, ruthlessly competitive. He was all business and had no tolerance for either bigotry—such as Roger Ailes’ complaint about “the Jews” in media—or mindless happy talk. Similar to Joe Biden, Welch was determined that a physical hurdle—his childhood stutter—was not going to be a barrier for him or others.

At the same time, he did not approve of ESG focus or corporate social responsibility, as it was called in his day. He was hostile to the concept of CSR that was developed by his predecessor Jones. In 1981, when Jones brought him to his first Business Roundtable meeting and introduced him to his new peers, he told me, he pulled out an order pad. “They were horrified,” he recalled. “I was there to do business but these do-gooders all wanted to play politician. That was how the U.S. lost its footing against foreign competitors.” His battles with environmentalists were also legendary.

He did not believe that any board committees should meet without him present. “Whatever they want to discus, I have the answers. Otherwise, their meetings are speculation and gossip.” He pushed CEOs to focus on shareholder value, reinvigorating a hidebound bureaucracy for a new era, and on developing new leaders as a top priority.

The most controversial part of his legacy was his increasing reliance on highly leveraged financial services to cover for uneven industrial investments, a move that took the company away from the equipment-leasing businesses they knew well into riskier insurance and derivative businesses, causing problems in his later moments—and for his successors. Unsuccessful moves such the purchase of RCA/NBC and Kidder Peabody, and the struggle to buy United Technologies–blunted by European rejection of what they saw as GE hegemony—also dinged his overall track record.

Frustrated over NBC’s faltering performance, he brought the CEO of Illinois Tool, Silas Cathcart, from GE’s board to try—in vain—to fix things before selling it off to Comcast. Still, rather than carve back the deal to get it through and retire on a high that would have left an unworkable mess for his successor, Welch swallowed his pride and withdrew from the effort—a magnanimous leadership action.

Worth noting: one of his interventions into NBC’s business operations was to push for what became The Apprentice. President Trump told me 15 years ago that Welch was envious of CBS’s successful and highly profitable reality TV show Survivor —and demanded that Jeff Zucker grab that show’s producer, Mark Burnett and migrate that same elimination game format to a business setting—with Trump on the throne.

American society loves to go through cycles, first lionizing and then vilifying our leaders. Jack Welch was not a god. But he was a historically great business builder, a fresh thinker, a genuine patriot, and an honorable man. No one who ever worked with Welch forgot the experience, and all saw shared time with him as a badge of honor.