How American Mythologies Fuel Anti-Asian Violence

The wave of attacks against Asian American and Pacific Islander communities over the last year fits into a long history of violence driven by rhetoric portraying Asians as disease ridden, writes Prof. Michael Kraus. At the same time, a parallel myth of Asian Americans as a “model minority” downplays and delegitimizes concern over anti-Asian racism and violence.

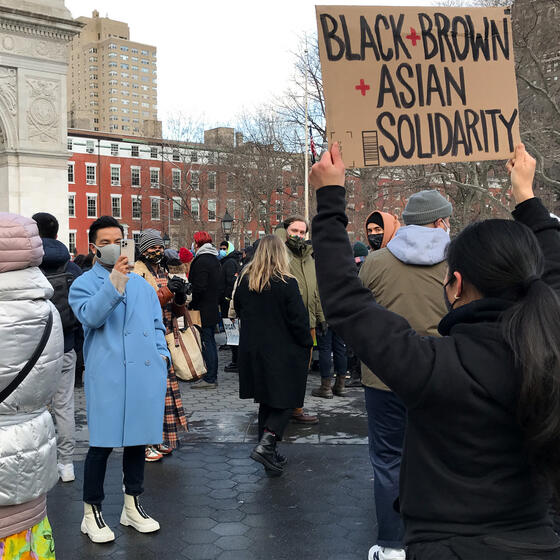

An End The Violence Towards Asians rally in New York City’s Washington Square Park on February 20, 2021. Photo: Dia Dipasupil/Getty Images.

There has been a sudden and rapid increase in hate crimes against Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) communities over the last year, and yet you may be hearing about it for the first time right now. One reason for this lack of national attention is that this violence does not fit neatly into narratives that are ascribed to AAPI communities.

As of August of 2020, the United Nations estimated 1,800 racist incidents, including acts of physical violence, against Asian Americans in the United States. The rate of these racist acts has not slowed in 2021. Last month, videos circulated on social media showing a disturbing violent attack on a 91-year old Chinese man in Oakland’s Chinatown and the violent killing of an 84-year old Thai man in a residential neighborhood in San Francisco.

These attacks are terrifying, and they are close to home. Oakland’s Chinatown is about two miles from my grandparent’s home, where my mother grew up, and where I spent time while attending UC Berkeley. AAPI students and faculty at Yale, where I now work, have expressed concerns both in public and in private about this uptick in racist violence. One chilling, and often ignored, aspect of this violence is how consistent it is with the history of AAPI communities in the US.

“Model minority mythologies of the Asian American and Pacific Islander community obscure how precarious our standing is in American society, and downplay and delegitimize concerns about racist rhetoric linking AAPI communities to foreignness and disease.”

There is a through line in U.S. history in which AAPI communities are conceived of as foreign, dirty, and disease ridden. Horace Greeley, a prominent political figure of the 19th century, called Chinese Americans “uncivilized, unclean, and filthy beyond all conception.” There are clear similarities between this rhetoric and the Trump administration’s messaging about COVID-19. One spokesperson for the twice-impeached former president said that “he wants everybody to understand, and I think that we need Americans to understand, that this virus originated in China.”

The history of AAPI rhetoric about foreignness and disease has coincided with violence across U.S. history. In 1875, San Francisco public health officials blamed Chinese Americans for an outbreak of smallpox and fumigated Chinatown by force, with no impact on the actual outbreak. In 1900, a bubonic plague outbreak in Honolulu led health officials to set fire to 41 buildings specific to Chinatown. In subsequent acts of racist violence against AAPI communities—including the murder of Filipino American Fermin Tobera, the forced internment of 120,000 Japanese Americans, and the 300 cases of documented violence and hate against Sikh Americans after the September 11 attacks—rhetoric around foreignness and/or disease has been close by. The violence happening now is part of a predictable and ugly recurring pattern in our nation’s history.

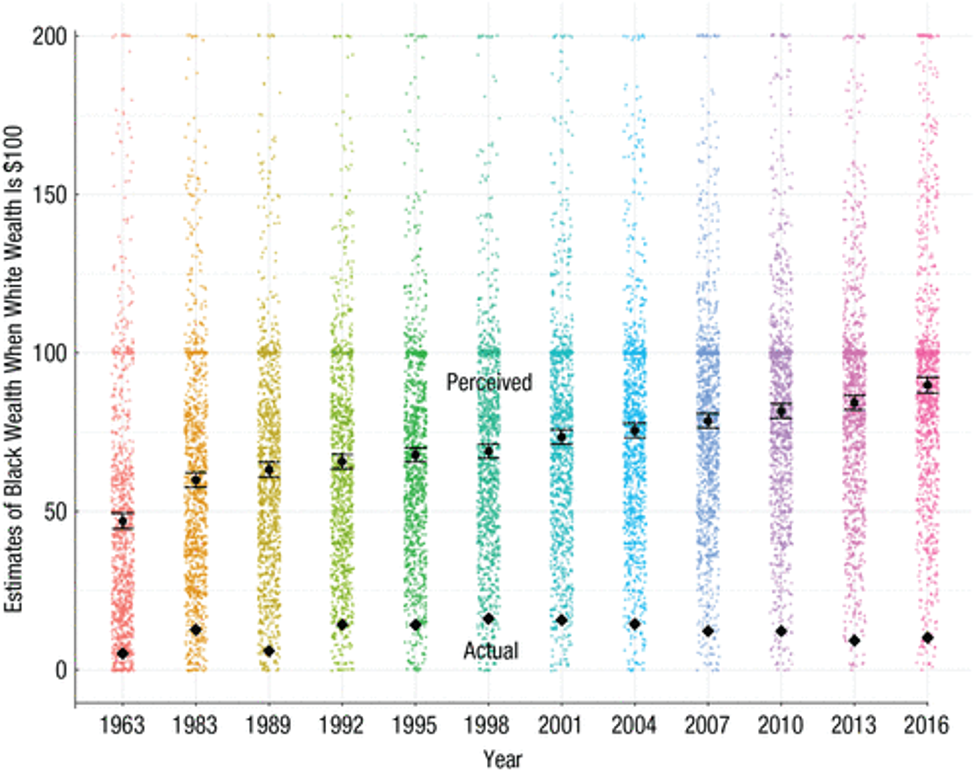

In this figure, perceptions of progress toward Black-White equality are set against actual progress according to economic data from the survey of consumer finances. Respondents perceived linear progress toward equality that doesn’t exist when examining the economic data.

As a social psychologist, I study narratives and how they can sometimes distort our understanding of opportunity and justice in the United States. My family was drawn to this country by American Dream narratives. My great grandfather, Shigeshi (Jimmy) Yamamoto, came to the U.S. around 1915 by jumping from a shipping boat from Japan. He came here in search of a better life and I think many families are similarly motivated. But, as is often the case, those narratives are compelling because they promise a better life and provide motivation for striving—not because of their basis in reality. Because American Dream narratives focus on stories of striving and success, they often paper over racism. In these narratives, some of which I and my co-authors have studied in our research, respondents expect racial inequality to linearly, and automatically, vanish across time. According to the narrative, racist violence of the past is a relic and progress is a guarantee.

AAPI communities as a whole have had some collective progress in the United States, measured in real economic gains. Researchers pin this group-wide success on the hyper selectivity of some higher-status Asian immigrant groups. Nevertheless, American Dream mythology has ascribed other interpretations to this success, referring to Asian Americans as a so-called model minority. In this specific mythology, AAPI community success implies the end of racism and the inherent and erroneous superiority of AAPI communities and values. In psychology research, we see adoption of this mythology in surveys where high status aspects of AAPI communities tend to be more top-of-mind for most American respondents than for other racial groups.

Model minority mythologies of the AAPI community obscure how precarious our standing is in American society. These narratives downplay and delegitimize concerns about the racist rhetoric linking AAPI communities to foreignness and disease, perpetrated by our government, that continue to put our communities at risk. These mythologies make media coverage of affirmative action lawsuits, advanced about AAPI communities but not in their collective interests, more common than coverage of the instances of violence that threaten our elders. These mythologies also stand as a barrier to solidarity with other communities of color who are persistently vulnerable to structural racism and who have historically stood against that racism for the benefit of us all.

It is my hope that we work to discard these American mythologies that cast racism as a problem of our ancestors. Racism is a problem for right now, one that we all share, and we must never be silent about it.