Holding Up a Mirror to the First Global Stock Bubble

Exactly 300 years ago, in 1720, Europe was seized by a mania for investing in the expanding trade in the New World; stock prices soared and then collapsed, in what is now recognized as the first global stock bubble. Yale SOM’s William Goetzmann, an expert in art and finance history, showed us the satirical prints that documented the financial cataclysm in the book Het Groote Tafereel der Dwaasheid (The Great Mirror of Folly).

TRANSCRIPT

The 1700s was a period of all sorts of innovation, new thinking. It was a period called the Enlightenment. The European states were in a constant state of war in the 18th century, fighting with each other but also pushing out into the rest of the world and developing colonial economic systems that eventually turned into something called the Atlantic trade, which was based fundamentally on the plantation system and slavery. One component of all of this was finance: the need of states to finance their wars, the needs of entrepreneurs to finance new inventions and discoveries, the needs of cities to create infrastructure. All of those things demanded capital.

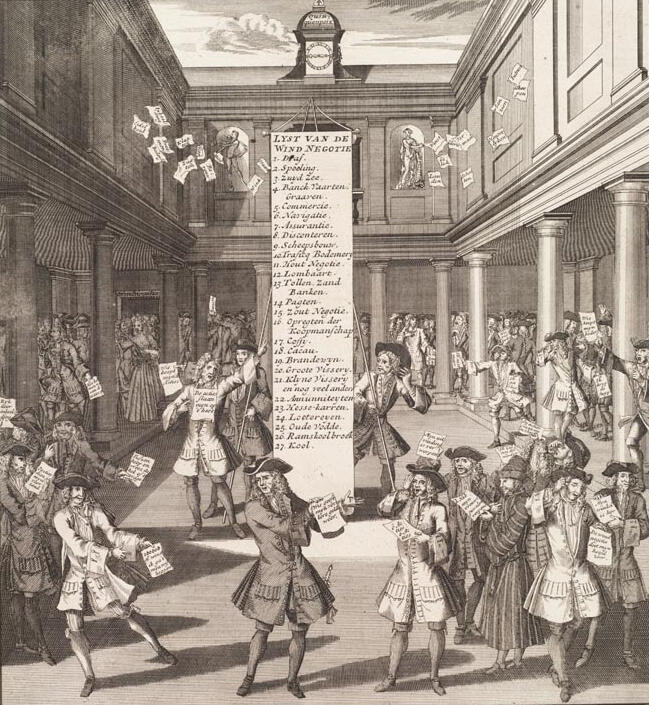

Seventeen-twenty was an amazing year for all sorts of things but particularly for the first great stock market bubble. It occurred all throughout Europe at least in three markets and probably in another dozen in small ways. The stated purpose of the book was to serve as a memory of mankind’s greatest folly. And every time some bubble happened later on in financial history people would turn back to this book and say, “Oh my gosh, it’s happened again.”But I’ll jump to some of the pictures at the time. Here’s a picture of what the actual stock market trading looked like in the 18th century.

You’ve got a stock exchange in this picture that is a courtyard and people, all the stock traders, are organized around this courtyard and we have a list of the things that they’re trading in. This list includes things like the South Sea Company and this bubble has been called the South Sea Bubble. Then it includes things like coffee and cocoa because this was also a period when people were speculating in commodities that were coming from the New World. Coffee and cocoa were being grown in plantations in South America and there was great conflict about whether France or Holland or England would be able to control the trade in these luxury items.

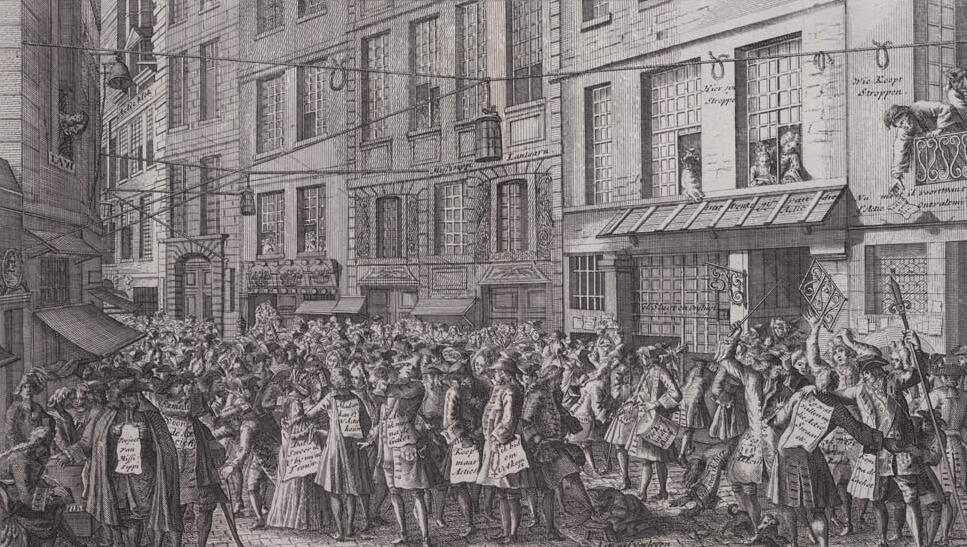

Here’s a picture of the place that the stock market craze really began.

It’s a picture of the street, one street in Paris called the Rue Quincampoix. It’s a rather narrow street. You can still go visit it. But what this picture shows is a huge crowd of people, all of them trading stock certificates, and people leaning out the windows calling to each other, and a picture of John Law, who was the person that had this idea for a big trading company to explore and colonize the whole territory of Louisiana in North America. So this picture shows the craze about people thinking that the trade in North America is going to make France incredibly wealthy and they got shares in this deal and they’re going to make a lot of money from it.

Here’s a picture that was used to promote the idea that Mississippi trade was going to be profitable.

Believe it or not, this is a picture of Louisiana. You wouldn’t know it because it’s full of mountains. It shows a trade between the Native Americans and the French explorers. It goes on to describe all of these wonderful things that Louisiana must have in it, the potential for mines and farms and plantations and the wonderful weather and all sorts of stuff like that. There was a lot of propaganda about what the trade in the New World could bring you.

Here’s a picture that shows how the artist describes the bubble and crash.

In this picture you’ve got a cliff that’s extending up to the right. You’ve got people doing all sorts of foolish things. You’ve got people chasing a cart and they’re going like lemmings up this cliff and they’re being led over the cliff by the goddess of fortune. They’re all chasing the fortune, they’re going up this cliff, and then they’re falling off.

The images have so much detail in them that you have to keep going back again and again and again and studying them. Even a single image like the image of this stock exchange—when you look at it you go, “Well, yeah, that’s a lot of stock brokers going and trading.” But then every single one of the pieces of paper has a little joke on it that has to do with the company.

The way that people look at images in the 18th century is quite different than the way we look at images now. When we go to Instagram, we consume lots and lots of interesting pictures and the Instagram images are designed to catch our eye, to excite us, to be beautiful, but not to cause us to focus for hours to study them. It’s exactly the opposite when I look at a print or a broadside or this book from the 18th century. It’s something you would come back to again and again and enjoy. And you might sit with another person and study these things and say, “This refers to this funny aphorism.” Or, “I think I figured out what this thing means.” Really, they’re ciphers, they’re visual jokes, they are puzzles.