Facebook’s Dominance Is Built on Anti-Competitive Behavior

Facebook and its subsidiaries, including Instagram, account for 75% of all time spent on social media. In a new paper, Yale SOM economist Fiona Scott Morton writes that the company took control of the industry by misleading consumers and buying up rivals. Scott Morton is the founder and director of the Thurman Arnold Project at Yale, which performs and disseminates research on antitrust policy and enforcement.

By Ben Mattison

In a paper released this month, Professor Fiona Scott Morton, an economist and an expert in antitrust policy, writes that Facebook has built its dominance as a social media network by misleading users and buying potential rivals. The paper, co-authored with David C. Dinielli of the Omidyar Network and published by the network, concludes that publicly available evidence, including the results of investigations in the UK, “suggest[s] that the methods used by Facebook to achieve monopoly violated U.S. antitrust law and harmed consumer welfare.”

Scott Morton is the Theodore Nierenberg Professor of Economics and the founder and director of the Thurman Arnold Project at Yale, which performs and disseminates research on antitrust policy and enforcement. In 2011–12, she served as the chief economist for the Antitrust Division of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Read the paper: “Roadmap for an Antitrust Case Against Facebook”

Scott Morton and Dinielli write that early in the history of Facebook, when it faced a number of credible rivals, the company differentiated itself by telling potential users that it would not “harvest” their data. But, they say, “Facebook began collecting user data without being fully transparent with its users or the public about what it was doing,” in part by building tracking into the plug-ins used by online publishers to let their readers share articles on Facebook.

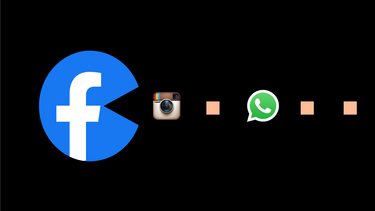

As Facebook grew, it purchased rivals, including Instagram and WhatsApp, the researchers say, “in a strategy that appears designed to stave off potential rivals rather than to take advantage of business synergies or efficiencies.”

The result is that Facebook and its subsidiaries now account for three quarters of all time spent on social media. Because “network effects”—the benefit a user gets from using the same product as other users—are so strong when it comes to social networks, it is nearly impossible for any other company to overcome Facebook’s lead.

“Without antitrust or regulatory intervention” Scott Morton and Dinielli write, “it is unlikely that anything is going to change. Facebook can collect monopoly rents, manage the flow of information to most of the nation, and engage in virtually unlimited surveillance into the foreseeable future.”

The authors don’t offer a recommendation for action against Facebook, which is under investigation by state and federal officials. But they note that potential remedies include reversing past acquisitions and imposing a requirement that Facebook work in concert with other social networks: “We can imagine a social network market that worked more like the current phone system: a user of one social network could post and reach friends who were members of different social networks through interoperability protocols.”

Scott Morton and Dinielli recently co-authored a paper outlining potential antitrust action against Google, which is also under investigation. Scott Morton talked with Yale Insights about the effects of Google’s dominance in the digital advertising business.