Do We Benefit from Trade?

Trade has been a lightning rod during the presidential elections, with candidates and activists in both parties blaming trade agreements for the loss of American jobs. Yale SOM economist Peter Schott talks about what his research shows about the effects of trade and how smart policy decisions can ease the impact on workers.

During the presidential election, candidates from both parties have gotten a warm reception for messages blaming globalization and major trade agreements for income inequality, stagnating wages, and loss of jobs in the United States. Bernie Sanders’ opposition to the Trans Pacific Partnership proved so popular with Democratic voters that Hillary Clinton reversed her position and came out against the agreement. Donald Trump has attacked NAFTA and other “bad trade deals” for putting American workers at a disadvantage.

Peter Schott, Yale SOM’s Juan Trippe Professor of International Economics, is an expert on trade with a focus on the effects of globalization on workers and firms. Yale Insights spoke with Schott about what his research shows, and how economists think about the advantages and disadvantages of trade.

Q: Your research about trade with China has been cited during the presidential campaign as part of the argument that bad trade deals are responsible for the loss of manufacturing jobs. What does your research actually show?

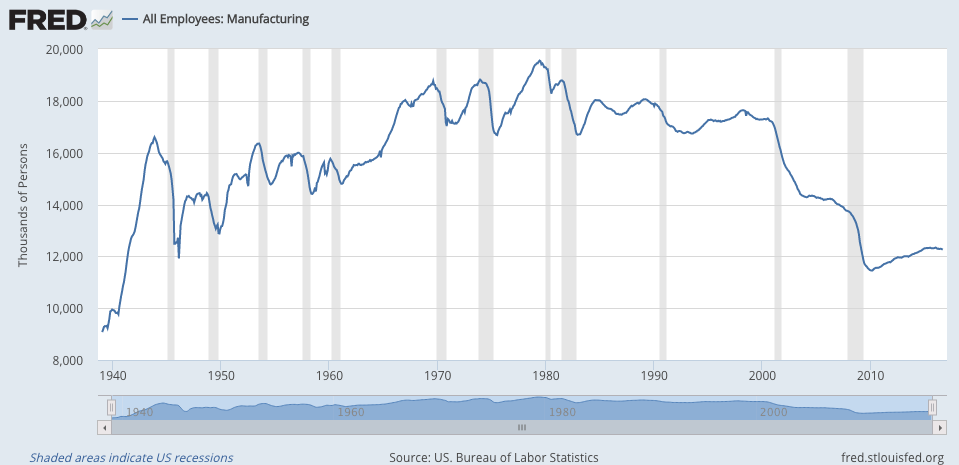

If you look at the data, U.S. manufacturing employment kind of falls off a cliff around the 2001 recession. And if you were going to connect that to international trade, one thing you might think is that maybe the U.S. lowered tariffs on some country in 2001 and as a result there’s a lot of import competition and employment falls. And the most natural country you might think that was happening with was China.

But the actual change in U.S. trade policy is different and quite interesting. The U.S. tariff schedule generally has two columns. There are relatively low tariffs that we charge WTO members and relatively high tariffs that apply to countries that are deemed non-market economies. That same trade law has an exception that says that the president’s allowed to ask for a waiver for non-market economies, and U.S. presidents began asking for that waiver for China starting in 1980. Congress has to vote every year to sustain that exception in order for it to be binding, so this creates a situation where the president could ask for it and the congress may or may not go along. If both of them are willing to give the extension, then tariffs, for the non-market economy, are basically at the relatively low WTO level. For China this was completely uncontroversial during the 1980s, but during the 1990s, especially after the Tiananmen incident in 1989 and then throughout the 1990s as geopolitical events between the U.S. and China heated up, those exceptions became controversial.

What happened in 2000 when China joined the WTO is not that the tariffs on Chinese goods dropped. It’s that the relatively low tariffs that the U.S. had been extending to China all along during that period now became certain as opposed to uncertain.

There’s a huge literature on investment uncertainty. One of the things that the introduction of uncertainty into the business environment can do is to cause firms to withhold investment. And if you think about globalization, it involves lots of investment on both sides. So, on the U.S. side, you might have had firms that wanted to outsource parts or production or find a new source of goods outside the United States. That requires a lot of effort, and they may have held back from doing that when low tariffs were dependent on a vote in Congress. And on the Chinese side, you might have had firms that wanted to scale up production to service the U.S. market, but there too, if they engage in that kind of investment and the vote goes the wrong way, then that would become unprofitable.

So the change in policy involved cementing in those low tariffs. Once that happened, is there an intuition for why the manufacturing employment would have fallen so starkly? Sure. On the one hand, on the U.S. side, there would be a lot more abandoning of U.S. production in favor of Chinese suppliers; on the Chinese side, there would be a lot more expansion, increasing competition in the United States. The data show that both of those things went on; not only is the employment decline concentrated in the sectors where formerly the risk was greatest—that is, the jump in tariffs would have been the biggest under the old regime—but it’s also the case that a lot more firms jump in. U.S. firms that hadn’t been importing from China before start importing. A lot of Chinese firms that hadn’t been exporting to the U.S. start exporting.

The thing that makes this interesting from an economic research perspective and useful for thinking about the future is that this didn’t involve the tariffs actually dropping; it was the certainty of those tariffs.

Q: What was the scale of the change in manufacturing employment?

Well, to give perspective, the highest number of manufacturing workers the U.S. ever had was 19.5 million in 1979. It had already fallen in the 1980s and 1990s, but not so dramatically. Then about 3 million manufacturing jobs are lost in about in a year and half, roughly speaking, after the change in U.S. trade policy. That occurs around the time of the 2001 recession, but that recession was not severe enough to explain the swift decline in manufacturing employment. There was another big decline in manufacturing employment during the Great Recession, but that makes sense in terms of the severity of that recession.

Q: There’s also been a lot of discussion about NAFTA during the campaign. Did it have a similar effect?

NAFTA is brought up quite often. But in terms of manufacturing employment loss, if you look at the data, you don’t notice a huge decline of manufacturing employment during the 1990s. So it is a little odd that so much of that discussion is oriented around NAFTA. Certainly, some firms moved south, so it’s not that nothing happened. It’s just that when you look at the data, the very dramatic decline in manufacturing employment occurs in the 2000s.

There could be a few reasons for why it comes up. It could be that NAFTA was the first salient opening of the U.S. economy to a lower-wage economy and so that’s what sticks in people’s minds. It was also a big topic of the election in the early 1990s—remember Ross Perot and the giant sucking sound? It also could be that one candidate wants to pin what’s happened in manufacturing over the last 30 years on a policy choice that was made by the other candidate’s husband.

A larger issue is that the discussion of manufacturing employment loss ignores data on manufacturing output, the values of products actually coming out of U.S. factories. Real value added in manufacturing continues to grow at pretty much the post-war average during the 2000s. The two trends together imply very large growth in labor productivity.

Of course, the reason why employment gets such so much attention, what the whole discussion of trade with Mexico and China really highlights, is the distributional implications of trade.

We all may be paying a bit less for the goods that we consume. We also may be getting access to goods that we wouldn’t have had before, like the iPhone, because of firms like Apple’s ability to use contract manufacturing abroad to assemble goods at a lower cost. So there’s a diffuse gain for all the people whose jobs aren’t lost. But then there’s this very concentrated loss among the workers whose jobs go away. If you look regionally where these manufacturing jobs have been lost, it’s been devastating for some of the communities, in terms of workers leaving the labor force and elevated mortality.

These distributional implications are sometimes portrayed as being unexpected, as if trade models and trade economists had no idea they could happen. But that’s not true at all. Trade models and trade economists have long recognized that while free trade increases welfare for countries in aggregate, it can create both winners and losers. The way to make everyone better off is to transfer some of the gains of the winners to the losers. But those transfers are at the border of economics and politics, whether you have the actual distributional policies that you would need to make everybody better off. If those aren’t there and the losses are particularly acute, it can lead to the kind of political outcomes we’re seeing during this election.

Q: Do the distributional implications that you’re talking about work their way into the media account? Do we think enough about those implications before we make a trade deal?

I think trade liberalizations tend to get sold politically as “the best thing for the United States.” They may not, ex ante, emphasize the potential distributional implications. What we’re going through now is maybe the blowback because those implications were not emphasized enough, and it turns out our social safety nets may not be sufficient to transfer enough of the gains to those who are losing.

But it’s not like this is a total mystery. Most trade deals—and NAFTA in particular—had provisions in them for trade adjustment assistance.

My reaction as an academic is that maybe we need to know more about the particular distributional policies that need to be put in place in order to facilitate reallocation. The worker that loses a job is worst off when they’re totally stuck—when their human capital’s been depreciated because their skills are for an industry that doesn’t really exist in the United States anymore, or when they have perfectly fine skills but there no longer is any activity where they’re living. We need more research into what policies might help them get unstuck.

Q: Is trade essentially a zero-sum game, with a winner and a loser? Is there any basis in economics for that view?

Well, you can build a model that tells you anything—we can build a model where trade is zero sum. But I would say very, very few economists think of trade as being zero sum. Trade enhances both countries. That’s the fundamental insight of international trade. And, by the way, that’s the fundamental insight of trade, even within borders. It makes both parties better off.

It’s interesting to think about why the idea of trade being zero sum is so entrenched. When Ricardo first wrote down these insights, the prevailing view was mercantilism, which is the idea that the best way to get ahead as a country is to export your goods and not import anything. You want to be selling to the rest of the world; you don’t want to be buying.

Ricardo writes down this model and makes this argument that not only is the weakest country in terms of making goods better off from trade but also that the strongest country’s also better off. It goes back to this insight that countries can do some activities relatively better than they can do other activities. And the more they spend their resources producing what they’re relatively better at, the more they can trade that for what they’re not relatively good at doing, and through that trade both benefits countries, since they’re emphasizing what they’re relatively good at.

That’s the fundamental intuition for trade: comparative advantage. That’s a very general insight. It governs transactions within a country; it governs transactions across countries.

Q: One number that comes up a lot when it comes to China is the trade deficit. From your point of view, how important is the trade deficit?

Here’s another case where a little bit of understanding of economics really helps. You have headline after headline that announces the U.S. has a record trade deficit. The exact same headline could be stated as, “The U.S. has a record capital surplus.” Because what’s a trade deficit? A trade deficit means one country’s buying more goods from the other country. The only way that’s possible is that the reverse is going on in terms of capital flows. If I wanted to state that even more emphatically, I could say the U.S. is the country where everybody wants to put their capital. If I say it that way, it doesn’t sound bad to have a trade deficit, right?

Think of the kinds of industries that we have here in the United States that are the envy of the world. Those are industries where investors around the world that have capital would like to deploy it. Just like with trade being zero sum, it might be intuitive that if we’re running a deficit it must be bad, like a firm that can’t sell its goods must be in trouble in some way. But that analogy breaks down when you’re trying to think of things at the scale of nations.

Q: You also hear politicians talk about whether the U.S. is competitive with other countries. As an economist, is that a meaningful question to you?

It depends what you mean by competitive. There are things that we are relatively efficient at doing and there are things that other countries are relatively efficient at doing. In the United States, relatively speaking, we have more human capital and more physical capital than we do raw labor. And there are other countries in the world—think of China, think of Mexico relative to the United States—where the opposite is true. Where they certainly have educated people and they certainly have physical capital, but they have a relatively larger pool of relatively uneducated workers. Of course, that’s changing in China, but in that setting, the U.S. is not going to be competitive at labor-intensive production. And moreover, the U.S. can take advantage of the fact that labor-intensive production is cheaper elsewhere.

I think one of the undersold stories of the benefits of trade is the effect that the ability to trade with other countries has on innovation. The one example I like to push is the story of Apple. When Apple’s thinking about producing something like an iPhone, if it had to produce it in the United States, then it might have cost—let’s make up numbers and say it might cost $5,000 or $6,000 to make it in the United States. There’s not going be much of a market for people who want to spend that much money on a phone. But if they can contract-manufacture with some other country that’s relatively efficient at the labor-intensive bit of this, while the United States supplies much of the content that goes into that phone in terms of technology, the U.S. is going to benefit from that asymmetry.

Q: You talked about the benefits that we get from trade and the additional benefits that we’ve gotten from entering into various trade agreements. Is there research that tries to quantify that benefit?

Some questions are just really, really hard to answer. And that’s more than just a dodge. I’ll give you one intuition for why it’s hard to answer. A major competing explanation for the kinds of employment trends we’ve been talking about today is technology. Manufacturing employment hasn’t declined because of trade; it’s declined because of technology. Everybody knows robots are coming and it has nothing to do with China and Mexico. It’s just the fact that the United States is slowly using more robots in manufacturing.

One could try to figure out what percent of the decline in manufacturing employment, and what percent of a country’s growth rate, is due to technology and what percent is due to trade. But the problem is, those things are related. It may be in anticipation of international trade with China that provides innovators with greater incentives to come up with labor-saving technologies. In that case, which part do you attribute to trade and what do you give to technology?

As much as I’m an academic and I love trying to answer these questions, there are some questions where putting a number on it is very difficult and we’re more persuaded by the direction of the result as opposed to the number.

I can imagine that people hearing that will say “Well, if you can’t tell me the numbers, maybe trade doesn’t do any good.” But again, I don’t think that’s the right response. Virtually all of the economics profession is pretty confident that there are mutual gains from trade.

But I agree it is very important here not to minimize the distribution implications of trade. I think that is a really important issue, and it’s at the crux of what’s going on in the election. I believe in free trade. We’re all better off with free trade. But if you look at what’s going on in communities that lose employment, there’s research that shows not only that the incomes are hit, but also that health outcomes are worse in these communities. And then you have to take into account the things that economists really aren’t good at quantifying—for example, if you have to move across the country, you’re leaving a lifestyle that you liked and who knows what you’re going to get.

I think that distribution of gains from trade should be the focus of policy. The right response would be to see what we can do for these workers to make sure that they enjoy the overall cadence in trade. That should be the focus of academic research and that should be the focus of policy discussions.

Academics reflect what’s going on in society, and I think there’ll be a lot more research into this. That’s not going help the workers that were dislocated during the 2000s. The dislocations from trade can be devastating. But that doesn’t shake my underlying faith in the logic of the overall enterprise. It means we should learn more about what we should do for these workers.

Interviewed and edited by Ben Mattison.