Can Congress Create Real Competition for Big Tech?

Last week, members of Congress from both parties introduced a series of bills to curtail the dominance of the major technology firms. We asked Prof. Fiona Scott Morton, an expert on antitrust and the director of the Thurman Arnold Project at Yale, if the proposed legislation would help level the playing field.

Do these bills help address your biggest concerns about competition in technology? Do they overreach?

These bills are an excellent start and there is a lot to like. But regulating is hard. So getting the exact words right in legislation that we want to create fairer outcomes in many different markets as they change over many years is tricky. There is always going to be room for improvement, especially in anticipating strategies platforms will try to use to escape their obligations.

You’ve argued that interoperability is important to increasing competition in social media. Would the proposed bill make a difference?

“The interoperability bill would transform competition in markets with a monopoly (or near monopoly) platform where the network effects keep out rivals, and instead those network effects would become inclusive and an entrant would gain from them also.”

Yes, it absolutely would. The interoperability bill (sponsored in the Senate by one of my senators, Richard Blumenthal) would transform competition in markets with a monopoly (or near monopoly) platform where the network effects keep out rivals, and instead those network effects would become inclusive and an entrant would gain from them also. We are familiar with this from contexts like email, where an entering ISP offers the service of sending email to any other email address on the internet. It’s great, and a user’s ISP does not affect who she can communicate with. But Facebook and other social networks don’t work like this—a Facebook user can only message other Facebook users. An entering social network must attract a user’s friends before she wants to join. Under interoperability of the type imagined in this bill, the entering social network can attract consumers by being a great home network (with good content moderation, for example), and the user can message all her friends regardless of their home network.

One of the proposed bills would make it easier to challenge future technology mergers and another would prevent discrimination between a platform’s service and a rival third-party service. Is that sufficient to address the dominance of firms that have bought up rivals in the past?

Clearly, being able to block future mergers isn’t a direct solution to problematic past mergers. But I do think a higher standard for all mergers is a good idea, and the advantage of this bill is that shifting the burden to the merging parties is very valuable in digital platform markets, where we now realize the past mistakes of enforcers. Because technology trends move quickly and products change over time, the nature of competition changes too, and courts can find it difficult to understand what the market is or was at any point in time. Putting the burden on to firms to show that their merger is not harming competition makes a lot of sense.

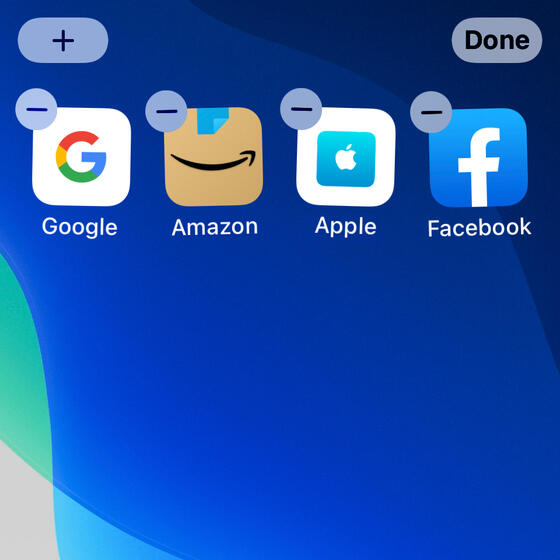

The non-discrimination bill is the most difficult to implement because it’s so specific. As I understand it, the bill would allow a business user on a platform—say, a music service or a search engine or a seller of shoes—to sue the relevant platform when it faces worse commercial conditions than the platform’s vertically integrated service. For example, perhaps the platform charges the third-party service a fee, but obviously cannot do that to itself; or the platform may provide its own search engine an exclusive pre-installed position, but not give that to rival search engines; or the platform may list its own products in a more prominent location than rival products that consumers like just as much.