The AI in the Doctor’s Office and Other News

Subscribe to Health & Veritas on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, YouTube, or your favorite podcast player.

Howie and Harlan discuss a breakthrough pain medication, studies on AI-assisted medicine, the explosion of sports gambling, and the health consequences of the shutdown of USAID.

Links:

A First-in-Class Painkiller

“F.D.A. Approves Drug to Treat Pain Without Opioid Effects”

“FDA Approves Novel Non-Opioid Treatment for Moderate to Severe Acute Pain”

“Peripheral Sodium Channel Blocker Could Revolutionize Treatment for Nerve Pain”

“Alabama to Beijing… and Back: The Search for a Pain Gene”

AI Screening

“3D mammograms show benefits over 2D imaging, especially for dense breasts”.

“The Robot Doctor Will See You Now”

USAID and Foreign Aid

“Trump and Musk move to dismantle USAID, igniting battle with Democratic lawmakers”

“What USAID does, and why Trump and Musk want to get rid of it”

“The Case For Global Health Diplomacy”

The Super Bowl and Legalized Sports Gambling

“Super Bowl LIX: Betting By The Numbers”

“Americans expected to bet $1.39B legally on Super Bowl 2025”

“Record 68 million people plan on making Super Bowl bets”

“Gambling problems are mushrooming. Panel says we need to act now.”

COVID and Flu

“The U.S. Is Having Its Mildest Covid Winter Yet”

“Estimated Vaccine Effectiveness for Pediatric Patients With Severe Influenza, 2015-2020”

Learn more about the MBA for Executives program at Yale SOM.

Transcript

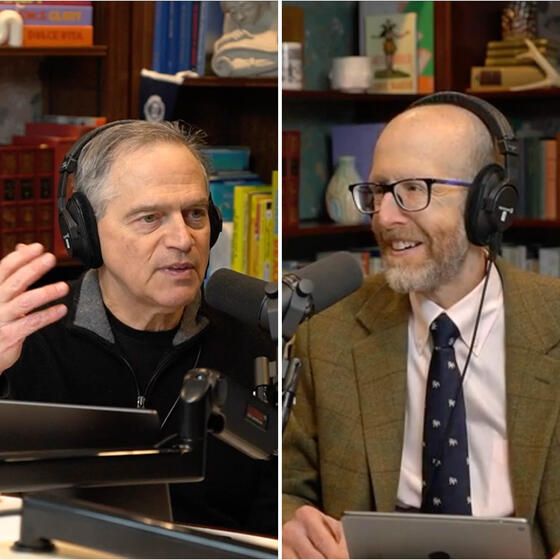

Harlan Krumholz: Welcome to Health & Veritas. I’m Harlan Krumholz.

Howard Forman: And I’m Howie Forman. We’re physicians and professors at Yale University, and we’re trying to get closer to the truth about health and healthcare. We typically have one episode out of every month to sit in the studio, and here we are. I get to actually see you.

Harlan Krumholz: Howie, I love seeing you. This is great.

Howard Forman: I do, too. Given my extensive social life, this is about the extent of it.

Harlan Krumholz: You and I, we talk, but we’re just running past each other all the time.

Howard Forman: I know. It’s totally true. So it’s fun to be here.

Harlan Krumholz: Well, this is great.

Howard Forman: Then there’s obviously a lot of news, so we could do this for hours.

Harlan Krumholz: Oh, my God. Okay, so look, I thought I would take you away from politics for a moment.

Howard Forman: Yeah, thank God.

Harlan Krumholz: Okay? So for the first time in 25 years, you know what just happened?

Howard Forman: Twenty-five years.

Harlan Krumholz: ...at the FDA, the FDA?

Howard Forman: God, I don’t know.

Harlan Krumholz: The FDA approved an entirely new type of pain medication.

Howard Forman: I heard that, yeah. Yeah.

Harlan Krumholz: It’s so new that I don’t even know how to pronounce it. Do you know how to pronounce this?

Howard Forman: No, I don’t. I’ve just seen the headline. I don’t know—

Harlan Krumholz: It’s like “Journavx.” They come up with this thing, it’s J-O-U-R-N-A-V-X. What do you think that sounds like?

Howard Forman: It took me four years to get semaglutide, so I’m happy with anything.

Harlan Krumholz: So this is developed by Vertex. And it’s a non-opioid pain medication. And it’s, again, I’m not sure the pronunciation of this yet, it just came out, but suzetrigine.

Howard Forman: Whatever it is.

Harlan Krumholz: Whatever it is. I’m a simple cardiologist. I don’t know what it is.

Howard Forman: So it’s not an opioid, not addictive, presumably?

Harlan Krumholz: So it works by blocking pain signals at the nerve level. So the idea is that some of these meds work by getting into your brain, but this is really at the periphery. And it targets these receptors, Nav1.7 and Nav1.8. Sodium channels. And like I said, unlike opioids, which act throughout the whole body, it really is just about getting to the point of a trigger for pain itself peripherally, but no euphoria, no respiratory depression. And what’s said is—this is the big deal—no addiction risk. So just to turn to the evidence, the FDA based its approval on two large-scale clinical trials where patients underwent surgery. One was tummy tuck.

Howard Forman: Yeah, yeah, yeah. Recovery from any type of surgery can be painful.

Harlan Krumholz: And another one was a bunionectomy. So I don’t know, this is going to go down in the history. These two things get approved. These are ... not to say they’re minor, but more—

Howard Forman: They may be elective, but they both are known to have pain associated with them.

Harlan Krumholz: They have pain associated with them. They compared the new drug with placebo and Vicodin and opioid. And the results were that this new drug reduced pain as effectively as Vicodin and had fewer side effects and better than placebo. It didn’t outperform the opioids, but it doesn’t really have to, if it’s non-addictive and it has a better safety profile. And so some people are saying this is a modest improvement rather than a game-changer. That may be, on how it controls pain. But giving people this opportunity is a big deal, because we think close to 100,000 people get addicted to opioids after taking a prescription opioid. So I remember Leslie had minor surgery and she came home with a prescription. I didn’t even notice. Next thing I looked ... They didn’t even ask her. They’d given an opioid. She didn’t take it. She didn’t need it. But it’s just become in our field, meaning medicine, we started prescribing these a lot, and for a lot of people, it’s a big deal. The one other thing is 31 bucks a day. It’s about 17 bucks or 16 bucks a pill, twice a day.

Howard Forman: But it’s a small molecule, presumably. It’s not a biologic. And so two things to say about that. One is that it’s first in class. We know that in most categories, first in class doesn’t even dominate the category 20 years later. But it gets you to the next level. You get to develop new drugs that might work better or might be more effective. And the second thing is, if it’s a small molecule, it’ll come off patent at some point and it will be pennies per pill. So there’s a lot of potential with that. And you got to be optimistic about something that’ll get us away from opioids.

Harlan Krumholz: So there’s a lot of excitement about it, and it seems to be something different. I have another piece to this story.

Howard Forman: Tell me.

Harlan Krumholz: You know that Paul Harvey thing where, “And now for the rest of the story”?

Howard Forman: Yes, yes.

Harlan Krumholz: So this thing was really unlocked because there’s a condition called Man on Fire Syndrome. Sometimes there are these families that can suffer from these really terrible pain syndromes. And there was a family in Alabama that was suffering from this condition, excruciating burning pain every day, and relentless. And nobody really knew why, and they couldn’t do this. So do you know who unlocked this story of this new opioid? Have you heard?

Howard Forman: No, I have no idea. No.

Harlan Krumholz: Steve Waxman.

Howard Forman: Oh, really? At our institution? Former chair of neurology.

Harlan Krumholz: My colleague, your colleague. Terrific person.

Howard Forman: Never knew that.

Harlan Krumholz: One of the nicest people you ever want to meet.

Howard Forman: And I think his wife listens to our podcast, because she has told me.

Harlan Krumholz: Meryl Waxman. We love her. She was an ombudsman for so many years at Yale and solved so many problems.

Howard Forman: That’s right.

Harlan Krumholz: So it turns out that Steve was working in his lab, studying how pain signals travel through the nervous system. And his research led to the discovery that this Nav1.7, one of the sodium channels, the sodium channel in nerve cells, acted as a pain amplifier. And that overactive Nav1.7 channels could cause this unbearable chronic pain. That was the case in this Alabama family that had the Man on Fire Syndrome.

So he had sort of worked this out in the lab, and everyone said, “Well, you’ve done this, but does it really apply to humans?” And then one day he learned of this family in Alabama. We have to get him on the show, because can you imagine that he actually finds a family that validates what he’s been doing on the lab? And also, people with mutations that turn this off don’t feel any pain at all. You may have read this book ... What was that series about The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo?

Howard Forman: Oh, yeah.

Harlan Krumholz: One of those series of books that was like her brother or something, you could punch him in the face and he wouldn’t feel any pain. So there are these people that don’t have this.

Howard Forman: Congenital indifference to pain, yeah.

Harlan Krumholz: It turns out if you have a mutation that turns this off as opposed to doing that, it can do it. So anyway, I just thought this was—

Howard Forman: No, it’s nice. It’s good to start with good news like that. And it’s nice to hear that we’re still making biomedical innovations that actually apply to people.

Harlan Krumholz: And what a story. We’ve got to get him on to talk about this.

Howard Forman: Yeah, that’d be a great idea.

Harlan Krumholz: It’s a Yale connection, anyway.

Howard Forman: Absolutely. You got it.

Harlan Krumholz: I’m trying to bring it back to... and he’s a great guy.

Howard Forman: I’m going to start with also a randomized trial in my field, and this comes out of Sweden. There’s a trial published in Lancet this week about using AI with breast imaging with mammography. And this is a follow-up. I believe we’ve reported on earlier evidence from this trial. It is really impressive. Using the AI, they were able to improve the detection rate of cancers, which is great, without increasing the false positive rates. So they weren’t finding false positives, cases that shouldn’t have found to begin with. And it reduced workload for the radiologist by 40%, so theoretically reducing cost in the long run, and/or maintaining a more sustainable workforce that is out there. The trial itself is still ongoing, and this is not even the primary end point. So there’s a lot more that we have to see to be able to prove that it works. But all indications are positive.

Now, there are some things about Sweden you have to know that are different from the United States at the current time. They are still predominantly using 2D mammography. We use what is called 3D mammography, or tomosynthesis. We generally only have one reader. They have two readers for every mammogram. We occasionally, depending on the practice, may use computer-assisted detection or diagnosis, which is different than the AI assistance that we’re talking about here. But it does give us hope of a new, real, meaningful application of AI. We’ve talked about a lot of fun things with AI, but this is something that can tangibly impact people’s lives, women’s lives, without adding cost and with improving quality over time.

Harlan Krumholz: Well, I got so many questions here for you. Well, let me just start with this technique. Can you just explain, what’s the workflow? How does this work? What exactly are they doing?

Howard Forman: Yeah, so in the United States, the workflow for mammography is one person reading it, but with computer-assisted detection, sometimes highlighting things. Their workflow is a randomized trial for about, I don’t know, 50,000 or 60,000 people in one group and an equal number in the other group. And in the intervention group, the AI identifies whether the case is a high-risk or a low-risk case and whether it requires a second reading or not. And it also identifies lesions. So it’s able to both determine potential lesions, but more importantly, determine which cases do not need a second reading. Some cases will still require two breast imagers to look at those cases. The 40% reduction is from getting rid of a huge number of second readers, second breast imagers sitting there and reading cases.

Harlan Krumholz: So it’s like the AI is a second reader?

Howard Forman: Exactly. It’s a second set of eyes.

Harlan Krumholz: Yeah, that’s interesting. And I wonder, if it comes to the States, whether that’s a separate charge. Is this going to be a service that people would... what I’m noticing in radiology is AI on top of or augmenting radiologists is a service, software as a service, in a way, that is getting billing codes associated with it?

Howard Forman: Yes and no. So computer-assisted diagnosis in breast imaging does have a billing code associated with it, even though it’s not terribly effective. But almost all the AI applications we use in my department right now have no additional billing codes. But it does give the radiologist more comfort. It allows the radiologist to read faster. We have evidence of that from at least some observational trials. And it improves accuracy. And we shouldn’t have to be reimbursed for everything. If something both allows you to work faster and improves your quality, the productivity payoff can pay for the quality payoff, and you don’t necessarily have to bill a third party extra money for that.

Harlan Krumholz: Yeah. The thing is, we want to incentivize innovation, and so that many of the companies are out there trying to figure out how to do this better. The question is, what’s a business model for this? Does a Siemens or Philips buy that algorithm, or can they charge—

Howard Forman: Right. It could be Hologic, in the case of breast imaging.

Harlan Krumholz: Hologic.

Howard Forman: Hologic’s the big breast imager. Yep.

Harlan Krumholz: So one other question I wanted ask you, because you were saying they’re so different in the two countries, so can we do comparative analysis to determine which one is better? For example, do they miss more breast cancers there or here?

Howard Forman: Yeah, there are some comparative analyses. I don’t know that we’ve ever done it in a perfect methodological way because their technologies are different. I mean, they do not use 3D imaging there like we do. We have good trials to show that 3D imaging is better. We have good trials to know that using MQSA, which is the federal law that governs mammography, that we do have reasonably high standards for breast imaging interpretation, but we do not have side-by-side. It would be great if we really could do side-by-side and figure out, is the double reader model necessarily better than our model in a meaningful way? And we don’t even know that.

Harlan Krumholz: So fascinating. Like you said, there’s so many differences, it’s hard to isolate what it is. But it’s so interesting that countries take such different approaches, and yet we still don’t know which one’s the best one.

Howard Forman: And look, the countries are just different. Sweden pays physicians dramatically less than we do in the United States. There’s so many differences culturally that their frequency of screening is different than it is in the United States—so much.

Harlan Krumholz: But we should be able to see net. But I guess then we’ve also got genetic differences and—

Howard Forman: Absolutely. A lot of differences.

Harlan Krumholz: Well, let me springboard off of that one, because I wanted talk to you about this op-ed that appeared in The New York Times. You might have seen it. It was by Topol and Rajpurkar.

Howard Forman: Oh yeah, just around the time of this article coming out.

Harlan Krumholz: Just around the time of this article. And what they’re doing is just what you’re talking about. They’re highlighting research showing that when radiologists, given AI predictions... here’s the thing. Remember we talked about this paper that had been in JAMA, where we said there was this automation bias, where sometimes the people were defaulting to the AI thing without thinking?

Howard Forman: I do remember that.

Harlan Krumholz: They’re basically saying that AI must be right. They’re talking about situations where people... it’s the opposite side of it. It’s sort of AI neglect, where people undervalue AI’s input even when it’s correct. And so they’re showing these cases that when AI is working independently, it actually performs better than when doctors are using it as an assistive tool. And the whole reason for that is that doctors are overriding it where they shouldn’t.

I mean, imagine pilots in a cockpit. There certainly, we’ve seen tragedies where we wanted the pilots to override the system because it was giving them bad information. But I think that there are actually more crashes when they override it when the systems are correct, and it’s human error that’s causing it. And so they’re talking about this, that a study where the AI alone had a 92% accuracy while physicians using AI only reached 76. So imagine, the AI is producing the same output. And they’re just saying, “If you just let the AI run—”

Howard Forman: It does better than a human.

Harlan Krumholz: “... it does better than when you let the humans override it.” And everyone’s always talking about “human in the loop”; we have to keep humans in the loop. And it may be that what we’re doing is we’re adding a point of error in the loop, because it just depends, right? If you’re using your own biases in overriding what the AI is saying, sometimes that can cause a problem.

Howard Forman: And look, there are second-order effects that we just don’t know about yet. So for instance, what happens when the human starts to rely too much on the AI? What happens when the human becomes so inured to using the AI for the detection of normal cases that they stop knowing what normal looks like because they’re not looking at enough normals anymore? And we don’t know what that will look like in the future. We can imagine that in 50 years, AI is going to absolutely perform better than human beings for almost all of the image interpretation. I truly believe that. But getting from here to there is going to have a lot of second-order effects that we haven’t necessarily worked out yet.

Harlan Krumholz: I mean, isn’t this a lot like the cars? I mean, if you really just let the cars drive, let’s just say maybe it’s not today, but soon ... But actually, the Waymos have data on this actually. And Tesla says they have data on this, that it’s not that they have zero accidents, but they have many fewer. And when humans are overriding these systems or actually just controlling the cars themselves, they’ll have many more.

I think it’s interesting because Topol then did a podcast on this question. We admire Eric, and he has been on the program, but he doubled down on this, where he was saying that research suggests that we need to completely rethink how doctors and AI work together. And they really argued that lots of people were assuming one plus one equals three. You get the synergistic effect and the AI’s helping. And again, I just hear people talk about this “human in the loop,” “human in loop,” meaning you don’t let the AI go by itself, but the human is part of it. But he’s talking about how it’s making things worse, and that maybe there are cases where we really shouldn’t let the human override it unless there’s a really strong, compelling interest. But I don’t know, what do you think about that?

Howard Forman: It’s hard to know. So we in our own practice actually at least try to encourage our radiologists to write in the report if they’re not following the AI finding and explaining it, because we find that that’s a lot easier than just allowing people to willy-nilly ignore something. And that does cause you to pause and sit there and say, “How confident am I that the AI is wrong in this case?” And in radiology right now, in the applications we’re using, AI is wrong a lot. It is not even close to being able to—

Harlan Krumholz: More than people?

Howard Forman: Way, way more than people. But is it improving us in our practice? I believe it absolutely is. It picks up occasional fractures, it definitely picks up occasional bleeds, and it picks up occasional pulmonary emboli that we would not otherwise find. And it’s sometimes easy to dismiss it and say, “Oh, it’s over-calling it.” Oftentimes, it’s not.

Harlan Krumholz: And here, we’re talking about replicating the work of the physicians. We also know that the AI is able to infer things that no physician can infer—

Howard Forman: It should be, yeah.

Harlan Krumholz: ... around prediction and so forth from these complex algorithms. So right now, we’re really talking about that. I think this is so important because we know that there’s a massive shortage of healthcare workers around the world. And it’s really important that we get this right, because if there are cases where it can work autonomously, and we have the monitoring systems and the checks and balances, the quality control in place, gosh, what about rural areas or anywhere around the world where all of a sudden this can provide them with experts—

Howard Forman: A hundred percent.

Harlan Krumholz: ... in places where you couldn’t detail somewhere there.

Howard Forman: I would ask you, like with EKGs now, we’re 35 years in, maybe more, from having machines that give you a preliminary reading of an EKG right off the paper. How is it that 35 years have passed and we still have cardiologists having to check everyone? How often is that wrong, or is there something material that has to be changed on a normal case, let’s say?

Harlan Krumholz: Yeah, my prediction is within five years, cardiologists won’t be reading ECGs. And that doesn’t mean that occasionally one won’t spit out and say, “We need help,” or something. But this is pattern recognition. And I said this to ... my daughter’s in medical school. She’s learning ECGs. I think it’s good she knows what they are. Why not become a good reader? But I said, “This is a skill that I don’t think you’ll be using in your career, because it’ll just be replaced.” Now, of course, we have this legacy system where people are billing for every ECG. Actually, they’re reading it days later—

Howard Forman: Days later.

Harlan Krumholz: ... when there’s no consequence to their read because actions have already been taken. And our system is having us read them. It’s tedious, soul-sucking for the cardiologist. It’s just for reimbursement.

Howard Forman: Right, right. It’s frustrating, but it’s existed for decades now. So I’m curious to see how that changes as well. I’m going to pivot to some topics that are direct current policy, because I just think they’re too important to talk briefly about. And I’m going to start off with USAID, because I think most of our listeners probably don’t know enough about USAID. It’s been widely reported that Elon Musk over the weekend basically said that under orders from President Trump, he is shutting down USAID. And so for our listeners, it’s a $50 billion independent agency, meaning it’s not quite under the State Department.

Harlan Krumholz: Who do they report to?

Howard Forman: So the administrator reports to the Secretary of State, but the entity itself basically is an executive branch up to the president. And it’s been typically led by a very high-level person. Again, it’s $50 billion.

Harlan Krumholz: When was it started?

Howard Forman: ’61. John Kennedy.

Harlan Krumholz: Wow. I didn’t realize it started that long ago.

Howard Forman: John F. Kennedy. Yeah.

Harlan Krumholz: Was that the kind of Peace Corps, USAID?

Howard Forman: I don’t know how it ties—

Harlan Krumholz: Because it’s all about soft power, right?

Howard Forman: Exactly. It’s primarily responsible for administering civilian foreign aid and development assistance for over a hundred countries. And it’s supposed to be distinct from the State Department in the sense that it’s not about, “You do this for me and I’m going to do this for you.” It’s about we believe ... as you said, soft power. We do this because it’s the right thing for the world. We want to help you. We want to help you emerge from whatever you’re involved in. The biggest place of aid right now I think is Ukraine, for instance, in the midst of a war. Other people in war zones are similarly receiving aid from USAID.

Harlan Krumholz: And then the HIV stuff is the big thing, right?

Howard Forman: HIV. So PEPFAR, again, not officially under USAID.

Harlan Krumholz: Oh, I didn’t realize that.

Howard Forman: But it administers it. So in other words, it facilitates it. And they’re the principal facilitator, with the Carter Foundation.

Harlan Krumholz: And just for people to know what PEPFAR is, just to—

Howard Forman: PEPFAR is the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief. I have to look down—

Harlan Krumholz: So it’s specifically for AIDS relief?

Howard Forman: AIDS relief. And its impact on—

Harlan Krumholz: George Bush.

Howard Forman: George Bush is where it started, and it is been bipartisan.

Harlan Krumholz: George W., George W. Bush.

Howard Forman: George W. Bush. Thank you. I’m sorry. Yeah. And it has had an enormous impact. I mean, it is helping us eradicate HIV/AIDS. We’ve talked about novel medications that are being used to reduce HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa. It would not happen without the facilitation of USAID and PEPFAR. And it’s not just that. It’s TB. It’s malaria, it’s so many things we’ve talked about on this podcast where we’ve given credit to Gates or Clinton or Carter foundations. It’s USAID that has the boots on the ground that facilitates this. And again, healthcare is not even its primary function, it’s just a key function. And so it is essential for how we carry out our, as you said, soft power.

I was thinking just yesterday, and I tried to email him, we’ll see if we’ll get a response, to Bill Frist, who was the former Senate minority and majority leader for the Republicans in the early 2000s. He’s a surgeon, he’s a member of the family that founded HCA, the hospital company. But he wrote an editorial, again probably 15 years ago, about medical diplomacy. Medical diplomacy is highly effective, that we can do good in other parts of the world and people will look to the United States as a leader and that we’ll have a better relationship with them. If we create a vacuum, if we’re not there, other countries, not our allies, will step into that breach. So USAID is essential. It is very disappointing to see what’s going on there. I admit I don’t understand enough about whether USAID—

Harlan Krumholz: But is it a redesign where the functions will continue, or are we going to stop doing this?

Howard Forman: So that’s the disappointing part right now. There’s no question that it’s not just a redesign, because they’re throwing away thousands of people who’ve already been employed. People have received notice to not come back. On LinkedIn today, there was a response from a gentleman who said that, “My very conservative religious son works for USAID, and he just got his notice that he’s no longer working there.” And he wrote this very nice—

Harlan Krumholz: Are they furloughed, or they’re actually fired. Do you know?

Howard Forman: Not clear, but I think—

Harlan Krumholz: I know things are changing so rapidly.

Howard Forman: And they’ve taken the things down from the walls in the building. So it has definitely made one feel like it is gone as its own entity. Now, Congress has written the checks, effectively, for this. It does now come under State. It won’t unwind immediately. But the sense is that all of these permanent workers, both in the United States as well as in the partner countries, are now being sent home. A lot of them are being sent home from other countries. It is unlikely to return in the form that it’s been four weeks ago.

Harlan Krumholz: This is the group that Atul Gawande was in, right?

Howard Forman: Correct. That’s exactly right, working under Samantha Power, who was the head of USAID. He was the head of, I think, global healthcare humanitarian aid or something like that.

Harlan Krumholz: Yeah, I saw an interview by him recently. I mean, I think he’s heartbroken around this.

Howard Forman: Completely. And I knew people who’d been in touch with him over the last couple of years who he had been encouraging to come work there so that there could be more continuity of leadership and not just a political appointment. It’s disheartening, to say the least.

Harlan Krumholz: Wow. I wanted to just take a moment. You know how the biggest holiday in the whole United States is occurring soon? Do you know what that is?

Howard Forman: I do. I do. It’s the day I work in the emergency room every Sunday in February. And we actually put the game on on the screen even as I’m working.

Harlan Krumholz: Yeah, Super Bowl Sunday. Do you have any favorites here?

Howard Forman: I tend to be an East Coast person, so I’m going to go with the Eagles, but I’ll admit that I have a lot of affection for Mahomes and for Kansas City and a lot of the players on Kansas City.

Harlan Krumholz: It’s hard to know because Kansas City... I always kind of root for something that’s never been done before, and the Threepeat. The Packers did it, before the Super Bowl. They had three championships.

But anyway, I wanted to bring this up to you because I’ve been wanting to bring this up on shows for a long time. I’m really concerned about the gambling problem in the U.S. And what’s happened is, with the legalization of gambling on sports and these commercials that are ubiquitous, we’ve really actually amplified the issue and problem. So for millions, actually, Super Bowl Sunday is not even about the game, but it’s about betting. A staggering almost $1.4 billion is expected to be legally wagered on this game alone. And that doesn’t even count all the money going on in underground markets. And by the way, Howie, you know they bet on everything. They bet on, how long is the national anthem going to be sung?

Howard Forman: I know, I know.

Harlan Krumholz: How many times will they show Taylor Swift?

Howard Forman: I know.

Harlan Krumholz: And this is not just a few hardcore gamblers. Last year, 68 million Americans placed a bet on the Super Bowl. And you know, by the way, what happens in March Madness with the basketball?

Howard Forman: Right. Absolutely.

Harlan Krumholz: But this is just ... every single game in America now is fair game for these things. And gambling’s always been around, but we’ve made it so instant, easy, accessible, 24/7 now on your phone. And for you to commit money is like nothing. You just push buttons. And anyway, I think—

Howard Forman: I think you’re onto something. And I think the reckoning is not going to occur from the Super Bowl or from March Madness. The reckoning will occur the next time that the stock market hits a major pitfall and a trillion dollars in wealth disappears from people’s Bitcoin accounts, or $10 trillion from their stock accounts. For a very long period of time, people have embraced the fact that you can make money out of nothing.

Harlan Krumholz: And of course, lotteries are the same way. I mean, meaning that it’s actually preying on people who don’t have a lot of resources, but—

Howard Forman: That’s right. But at least those are zero-sum games. And I mean that in a good way. There’s no Ponzi scheme built into that.

Harlan Krumholz: Well, the state’s taking a cut. They’re not returning all the money.

Howard Forman: That’s right. But what I mean is that we literally have witnessed the creation of trillions of dollars of wealth in cryptocurrencies and NFTs and other things that almost certainly, and obviously, prove me wrong—

Harlan Krumholz: But how are you connecting that with gambling?

Howard Forman: Because I think when people have a reckoning about how much money they’ve put at risk, where they thought they weren’t putting anything at risk... they don’t think they’re gambling about that. But the magnitude of the losses that may accrue to some of the most vulnerable people is much larger there. But I think you’re right. People have become ... It’s so easy to go on Robinhood, which is a trading platform right now, trade meme stocks, trade crypto. And then this past week, they tried to introduce Super Bowl betting. And the CFTC said, “We can’t let you do that.”

Harlan Krumholz: People were betting ... of course, they were betting on the presidential election. There were all these markets, unregulated markets.

Howard Forman: Right, everything.

Harlan Krumholz: It said that there are 2.5 million people in the U.S. who have a severe gambling problem, a severe gambling problem.

Howard Forman: I believe it.

Harlan Krumholz: And 5 to 8 [million] who have a serious gambling problem. So they have one, but it’s not at the point where it’s destroying their lives.

Howard Forman: And we can’t measure it. It’s not like when you come into the hospital, we draw blood and we know you have it. And I think they hide it.

Harlan Krumholz: I really think this is a public health issue.

Howard Forman: I agree. I think it’s going to be a big problem.

Harlan Krumholz: I don’t know if we can put the genie back in the bottle, but it’s something.

Howard Forman: We’ll see it soon.

Harlan Krumholz: All right, well, wrap us up with something good here at the end.

Howard Forman: Yeah, I mean, I don’t know if it’s good or not, but I think it’s worth pointing out that we are late in the COVID season, late in the flu season right now, or at least far enough along.

Harlan Krumholz: RSV.

Howard Forman: And RSV as well. And while we have seen a lot of cases in the emergency room, we have definitely had a mild COVID season in terms of hospitalizations, in terms of deaths, and even in terms of presentations to the emergency room. Flu has been a little bit worse, I believe, than in prior years, but even so, has not been of pandemic levels. It’s not a worrisome trend there. RSV has been pretty bad among kids, but again, hospitalization deaths have been relatively muted. And so I just want to highlight that there was a study at the end of last year in JAMA Network Open that basically said that our flu vaccine effectiveness in children is at least 50%, meaning there’s a 50% reduction in likelihood that you would need to be admitted to a hospital for a critical or non-critical admission.

And I think it’s worth pointing out that we’re halfway through the season right now. It has not turned out as bad as it could have been. We’ve had very poor COVID vaccine uptake right now. And unfortunately, the CDC websites have not been providing the data that we used to get about that. But we know from right before the present administration moved in that it was already a very low uptake season. And we’ve gotten away with it. I do think that the evidence about the vaccines, particularly flu vaccine and even the COVID vaccine, are fairly strong, particularly for people at high risk: elderly and those with multiple comorbidities. And so for those who’ve made it this far without a vaccine, that’s great. I would strongly urge anybody in the high-risk category still consider getting a flu or a COVID vaccine, because we’re still at just past the peak of the season.

Harlan Krumholz: You’re just swimming so upstream, baby. I don’t know.

Howard Forman: I know, I know.

Harlan Krumholz: I think people who wanted to get them have gotten them. I don’t know. We’re in an interesting moment where ... I don’t know. People are losing—

Howard Forman: Skepticism is very, very high. The reality, the math, the science is very solid.

Harlan Krumholz: But I think people are raising these interesting questions, which is, we do a study of the vaccine. The vaccine evolves over time. How much are we learning it with each season? I mean, how are we embedding studies so that we can sort of figure out what’s going on with the most recent vaccines? I mean, we’re not embedding those.

Howard Forman: So the nice thing about the JAMA study, which again, it’s observational, it’s not really prospective, as you’re suggesting, but it does give us ... I think it was four years’ worth of data around flu vaccine effectiveness in children. And it does give you a pretty solid sense that it’s working well. Now, the COVID vaccine in children is not something I’m talking about, here on the podcast. I think there’s a lot of issues that we could talk about when it comes to COVID vaccination in young, healthy individuals. But the flu vaccine has consistently been proven to be safe and effective, reducing morbidity and hospitalizations.

Harlan Krumholz: And I’ll just say, I got the flu vaccine, I got the COVID vaccine, I got the RSV vaccine.

Howard Forman: Me, too.

Harlan Krumholz: I mean, I believe in that, on average, these are good things. But yeah, we’re in a moment.

Howard Forman: Yep. And I’m going to keep bringing it up, and I know you will too. And I think the importance for us on this podcast is just keep bringing people science and keep explaining things for people to make their own independent decisions and hopefully look for a better future.

Harlan Krumholz: You’ve been listening to Health & Veritas with Harlan Krumholz and Howie Forman.

Howard Forman: So how did we do? To give you feedback? Keep the conversation going, you can email us at health.veritas@yale.edu, or follow us on any of our social media, particularly LinkedIn and Bluesky at the moment.

Harlan Krumholz: Yeah, we love the feedback. Actually, we got good feedback this week when Mark Siegel sent us a note.

Howard Forman: Oh, that was very nice of him. Absolutely.

Harlan Krumholz: It was terrific to hear from him.

Howard Forman: And we do almost every week have somebody out of the blue say a nice thing. It makes it worth—

Harlan Krumholz: If you’re listening, feel free to reach out to us. Rate us. Helps people find us.

Howard Forman: And if you have questions about the MBA for Executives program at the Yale School of Management, reach out via email for more information, or check out our website at som.yale.edu/emba.

Harlan Krumholz: And we’re so grateful to be sponsored by the Yale School of Management, the Yale School of Public Health. We’re so lucky to be working with our terrific student researchers Inès Gilles, Sophia Stumpf, Tobias Liu, and with our superstar producer, Miranda Shafer, who we’re always so happy to work with.

Howard Forman: We’re very appreciative of them. And Tobias joined us in the studio today, so we’re also appreciative of him coming by.

Harlan Krumholz: They’re just amazing.

Howard Forman: Talk to you soon, Howie.

Harlan Krumholz: Thanks very much, Harlan. Talk to you soon.