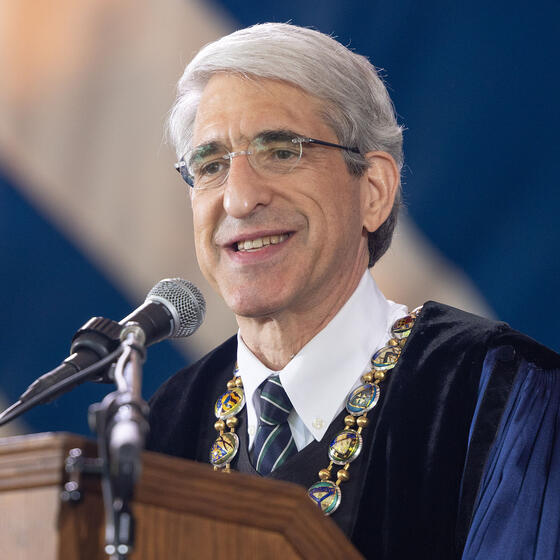

Peter Salovey: A More Unified, Accessible, and Innovative Yale

Subscribe to Health & Veritas on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, YouTube, or your favorite podcast player.

In the 100th episode of Health & Veritas, Howie and Harlan are joined by Peter Salovey, the president of Yale University and a pioneering psychology scholar. They discuss Salovey’s tenure as president, which ends in 2024; the future of the newly independent Yale School of Public Health; and Salovey’s influential research on emotional intelligence.

Links:

“Statement regarding YSPH transitioning to an independent school at Yale”

Peter Salovey: “Emotional Intelligence”

Yale School of Medicine: “Medical school and health system form a new affiliation”

“President's house will be a home”

For Humanity: the Yale Campaign

Learn more about the MBA for Executives program at Yale SOM.

Transcript

Harlan Krumholz: Welcome to Health & Veritas. I’m Harlan Krumholz.

Howard Forman: And I’m Howie Forman. We’re physicians and professors at Yale University and we’re trying to get closer to the truth about health and healthcare. This is a very special episode of the podcast today. Harlan, do you know why?

Harlan Krumholz: Is your mom coming on?

Howard Forman: My mom is not coming on. Although that would be very special. No. In fact—

Harlan Krumholz: Who do we have today? Who do we have today?

Howard Forman: In fact, it is our 100th episode, and we have a very special guest. President Peter Salovey is Yale’s 23rd president and the Chris Argyris Professor of Psychology. At the beginning of this academic year, President Salovey announced that he will step down as president, a position he has held for over a decade. During his extensive Yale career, President Salovey has also served as provost, dean of Yale College, dean of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, and as chair of the Department of Psychology. In addition to his institutional leadership, which has included numerous accomplishments, such as launching the Jackson School of Global Affairs and transitioning the Yale School of Public Health into an independent school, President Salovey was an early pioneer of the theory of emotional intelligence and is published extensively with a focus on the connections among emotion, health communication, and health behavior.

He received a BA in psychology and an MA in sociology from Stanford before coming to Yale, where he has been ever since. He earned a master’s degree and a PhD in psychology before joining our faculty in 1986. I want to first welcome you, and I’m going to jump right in and ask you the big question and that is: This is a healthcare podcast. We do this jointly with the School of Management and the School of Public Health, and this is a very big year for our School of Public Health, and you have been instrumental in allowing the School of Public Health to be a fully independent school. I’d love to hear about how your history at Yale has informed your ability to do something that other deans had told me would be impossible.

Peter Salovey: Well, thank you first of all, Harlan, Howie. Appreciate the invitation to come on your podcast, and it’s great to see you both, although I was hoping to see your mother, but it’s really a pleasure to be here and to celebrate the 100th podcast with you. So I think the question was, how are we, why are we taking the School of Public Health independent? I think to attract the very best faculty, either as faculty with secondary appointments who might be elsewhere in the university, but especially primary faculty in the School of Public Health. They expect the public health school to be self-governing, setting its own curriculum, having its own standards for promotion and tenure and who it wants to hire and the like. And so I think it makes it a more attractive school for accomplishing my goal, which is that it should be among the very, very best schools of public health in the world today. I think when I talk about a more unified Yale, it’s one in which disciplinary boundaries don’t get in the way of our doing our very best work.

Harlan Krumholz: Well, I mean there are a couple of things, Peter. First of all, I just want to take the opportunity to thank you. These years of service, these have been great years for Yale and the point that you make about this is I think emblematic what Yale is. Really, there are no boundaries. I mean, it’s a very nice community. People can collaborate across disciplines.

I wanted to ask you, in talking about the School of Public… You and I had the opportunity to participate together—you actually were leading this effort. Remember 20 years ago, when we looked at whether or not the School of Public Health should become independent, and we were weighing these issues, and it seems sweet to me that at the end of your term, you’re able to actually realize this vision of an independent school of public health, but for people who are listening, you are starting to get at this, but what’s the real meaning of that? I mean, for a school of public health, is it that you—by the way, great job recruiting Megan Ranney, a terrific superstar, to be the first inaugural dean of an independent school. But what are the real advantages as we go out into the world and say it’s a new day for public health at Yale because of what we’ve just done? What is it that makes it a new day?

Peter Salovey: Yeah, I think a few things. One is first of all, just the symbolic value of focusing on public health, saying it deserves status as one of our professional schools. But more important than that symbolic value is, I would say, two pragmatic concerns. One is self-governance, so public health should be able to set its own curriculum for its MPH and its PhD students. Public health should be able to choose its own faculty, should be able to decide on its own criteria for promotion for tenure, should decide on what its own strategic priorities are with close ties all over the university and with an openness to listening to what others say all over the university, but ultimately with its own authority to make those decisions.

I also think the last issue is financial. Public health should be able to make its own financial trade-offs. What we did to make the school independent, the first step was to put it in budget equilibrium—that is, it has the financial resources to pay its own bills, its financial robustness rises and falls with the university’s endowment and the university’s overall budget, but it has its own, but it works on the same model as everyone else. That allows the public health school to make trade-offs. It also allows the public health school to benefit when the endowment does better than our budget models suggest it should. It also allows the public health school to benefit directly from its own, the generosity of its own alumni and friends, and it’s not lost on those alumni and friends that an independent public health school is a more attractive target.

Harlan Krumholz: Yeah. And by the way, I’m hoping that our alumni will see this as an immense opportunity to invest in what’s going to be the leading school of public health in the nation as this starts to grow out from what seeds you’ve planted now. I mean, and by the way, an illustrious history, let’s not neglect that, but now with this independence, it’s a new day for public health at Yale, I believe.

Peter Salovey: Yeah, exactly. A new day. And what’s interesting is we’re going to be a very top public health school in part because the independence makes it easier in a way to collaborate across boundaries.

Harlan Krumholz: Yes, yes.

Peter Salovey: Right. Because you’re collaborating on equal footing.

Howard Forman: And I want to come back to something you’ve said, but that to me is very obvious and that is that many of our schools at Yale are extremely interconnected in ways that other institutions are not. So I think about the School of Management’s connection with the forestry school and the School of Public Health and the Law School and the Law School’s relationship with the School of Public Health and obviously the medical school’s connection to the nursing school and the School of Medicine’s…

Peter Salovey: Yeah. Even public health has joint programming with the School of the Environment around environmental health.

Howard Forman: Exactly.

Peter Salovey: Just as an example. It’s all over the place. Law and management in particular.

Howard Forman: And so as president I think people may not even understand what the role is of president. There’s also a provost below, but as president, how are you able to foster those areas of interconnection so that the greater Yale benefits from these types of programs?

Peter Salovey: Yeah. My first day—it wasn’t even my first day as president, it was the day I was announced to be president, which was about six months before I became president—I said Yale needed to be more unified. Yale needed to be more accessible, Yale needed to be more innovative, and all of that would make us that much more excellent. So part of what a president does is try to set a vision around which lots of ideas can flow, but there’s a couple of other things we can do again on the ground. One of them is try to put people together. So look at what is happening next door to the School of Public Health at 100 College Street. We have a couple floors there occupied by the psychology department. In fact, my faculty office is there.

Harlan Krumholz: Yeah, I noticed you gave them the top floor. You gave them the top floor.

Peter Salovey: Yeah, exactly. They have the top. Below them is the neuroscience department from the medical school.

Harlan Krumholz: Right.

Peter Salovey: In between is a new multidisciplinary institute called the Wu Tsai Institute studying human cognition, and then there’s shared equipment in the building that everybody is using. Right. So one of the things you can do is through collocation, make it easy to collaborate. Right. You don’t have to walk across campus or even open up a Zoom call. You can simply walk down the hall or down a flight of stairs and collaborate. I think the other thing that fosters collaboration in addition to people just running into each other, which I think is super important. By the way, that building also has a cafeteria and a coffee shop and a gym, and don’t think that isn’t about getting people to get to know each other across disciplinary boundaries as well. But in addition to that, those physical spaces, yeah, you can create resources that are available when people collaborate across boundaries. So special seed grants, special innovation grants, special support for working together on proposals that go outside the university.

When I was starting out my career as professor, I was an assistant professor in the psychology department. I didn’t have any joint appointments at that time. I was doing work on emotional intelligence, as you mentioned, but I was also doing work on how people think about health and illness and conceptualize it. That was moving me into how we communicated about health and illness and moving me toward how to help health messaging become more persuasive and more motivating and what’s its connection with actual health behavior?

And I discovered that there were people in the School of Public Health with similar interests, but how did I discover that? I discovered it because the university brought us together to work on a grant proposal together around cancer prevention, and they asked me, we don’t have enough behavioral science in this grant proposal. Could you, with your psychological perspective, think about the questions you like to ask, but with a cancer outcome, with behavior relevant to cancer prevention? And then later, same kind of thing happened around HIV/AIDS, and so I developed these networks of people who thought about cancer prevention and this network of people who thought about HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment, all because we were pulled together to work on proposals together ultimately and then be part of it. Both of those proposals were successful, and we ended up having centers that really broke down the barriers among disciplines.

Harlan Krumholz: One of the things I wanted to talk to you about was your thoughts about medical schools and the way in which they fit within universities. Over the last 50 years, there has been an asymmetry of growth within major universities because of the influx of NIH funding and the sort of largest of clinical care revenues, honestly, that have led to budgets on medical school sides that can rival what is happening almost on the rest of the campus and enlarging faculties to a point where almost half the faculty could consider to be part of the medical schools. In some places like Harvard, the hospitals themselves actually became employers of the doctors, and they got affiliations with medical school at Yale, and I think this is a great advantage at Yale.

We’re full-fledged members of the faculty, but does this keep a president up at night sometimes because there is some risk because of the way that health policy goes and the way in which NIH goes that can really affect funds flow in revenue streams. And you’ve got all the funds committed to faculty. And anyway, I just wondered, does that enter your thinking at all or does it, in terms of strategically, what the future of this is going to look like?

Peter Salovey: So, sure. And it’s something we do talk about a lot. Our trustees have a medical school committee that thinks about risk as well as the rewards of having—

Harlan Krumholz: The rewards. I should have mentioned that.

Peter Salovey: What you described is happening at Yale. The university has a $5 billion budget as a whole, and almost 50% of that budget is the Yale School of Medicine and 50% is everything else. And what has really changed in the last decade is clinical revenue. So revenue from research used to be the leading source of revenue for the medical school and the university, but now it’s clearly clinical care. Those lines crossed some years ago. I don’t remember exactly the year when they crossed, but call it about the time I first became president and those lines have departed. So the big risk is uncertainty about basically how healthcare is going to get paid for—

Harlan Krumholz: Right.

Peter Salovey: ...what the model is for paying for healthcare. Many of us, the two of you especially, you talk about this, and I generally have the same view you guys do, recognize our system is broken, and it needs to be fixed, and we need to move to something quite different from what we have now. How does that affect funds flowing from in particular the Yale New Haven Health System back to the medical school and how does that affect care delivered in a academic medical center context? We are more expensive in delivering that care, but we’re delivering cutting-edge care that is scientifically based, and how do we do that? Hopefully we can build, there are reserves in the system that could get us through short-term crises and if revenue were to be significantly affected negatively, we would probably have to build a new model. I’m pretty comfortable with the model we have now because it’s working and working well, and I think we have the flexibility and ability to adapt to different models of healthcare reimbursement.

Harlan Krumholz: Just since I have you, I’m going to give you a quick challenge on this. So I think that the model may be working on a financial basis, but if you look at the health of the people in the state of Connecticut and in the county of New Haven over the last 20 years, despite the fact that more money has flowed into the system every year above and beyond inflation, we have very little evidence of a return on that investment by our health system in our medical school on the actual health of people living in New Haven, if you look at life expectancy or you look at almost any other measure of health. So I also, I mean this is why I think I feel that we need a balanced scorecard that on one hand we’re able to, you manage the funds flow to be able to support an institution, that’s definitely a checkbox, but are we clear that actually the end result of what we’re producing is helping the world?

By the way, the whole United—you could just say, okay, that’s just New Haven, what about we focus on the country? Okay, the country’s life expectancy has gone down. All the health parameters have worsened over 20 years. Okay, no, but we’re focusing on the world. Okay, the world’s health parameters have gotten worse. So on our watch, by the way, this is Howie and me and this is our fields, we’re here so we have to take responsibility for it, but as a school, I also would like us to see this balanced scorecard where we can say to the trustees, is there evidence of the end result of care writ large, and this gets to public health, I guess. On a population level, are we actually making any progress? And instead we’re just raising money, spending more money and less return.

Peter Salovey: Yeah, well I don’t disagree with that analysis. I mean those are data, and those data are really quite self-evident. You did say something important, which I think is you can look at New Haven, but you could also look at the whole country and it’s the same thing, which suggests that this isn’t something that Yale is causing but rather something is broken in the whole system. And I’m not sure what, for the most part, as revenues come in, what do we spend them on? We spend them on research and clinical care. So it’s not like we’re expecting funds to flow out of the medical school and somehow subsidize the rest of the university. Basically what comes in the medical school is spent by the medical school. And some years we have deficits and some years we have surpluses, but essentially it’s a balanced budget.

I think our obligations in the rest of the university are to do everything we can to keep central costs, administrative costs, overhead costs manageable, so that as many of those dollars can go back directly to supporting additional research, to supporting great clinical care and to educating medical students and other kinds of students. But the data aren’t very good, but I think that’s because the whole system is not optimized. Let me just say one thing we can also think about and that’s kind of hovering behind here. You just cited data, and I’m data-driven; Howie, Harlan, you guys are data-driven. We need a system that is far more data-driven because when we do, we make better decisions and Covid-19 pointed that out to us.

We went into Covid, into the pandemic even before the first cases of community transmission were noticed in Connecticut, two months before actually. And we said, we were already meeting and saying “What do we need? What do we need to do?” And I put together a group—you know about this because you have great familiarity with it—put together a group of essentially public health advisors and said, “We’re going to need to collect data and we’re going to make our decisions based on the data.”

We said, “What are our goals? Our goals are to never have a big giant outbreak on our campus.” It’s another way of saying keep everybody healthy, as healthy as we can, to not be the vector of transmission with the community that surrounds us because the community that surrounds us doesn’t have the same resources and has other health stressors in their lives, housing, food, et cetera, poverty. And the third was not to overwhelm our hospital. Right. That was where, remember “flattening the curve” and all of that? Right. Not overwhelm our hospitals so that truly sick people were being displaced by our students who are getting care for Covid. And we accomplished all of those goals because our public health modelers had great data collected from traditional epidemiological sources to the virus in sewage that gave us very localized information about—basically anybody flushing a toilet in New Haven was contributing those data. And we knew from where it was flowing. We followed the data, and sometimes that meant being more aggressive, keeping people off our campus, doubling down on testing, having incredibly careful contact tracing and isolation.

And sometimes it meant we could be more aggressive in letting people come back and in doing more of our educational program. Right. Because the other part of our goal was to keep our mission of research and education going during all this. And I think history will show that our campus result was not, it was still a pandemic, people were quite sick, but was one of the better outcomes among university campuses, and it’s because we followed data. And I think that’s part of the solution for fixing medicine, right? Go where the problems are instead of necessarily just where there are people who can afford fancy care.

Howard Forman: Before we run out of time, I want to ask you, you’re the first president in a long while to have lived in the, quote, “President’s House of Yale University” with your lovely wife, who’s also a former public health professor here at Yale. What informed your decision, and then, would you recommend that the next president make that same decision? Because that is not an easy decision to make.

Peter Salovey: Yeah, sure. It’s an interesting one. A couple of thoughts. The President’s House is an interesting arrangement. It’s this huge mansion within which we have an apartment, and that apartment’s up on the third floor, the top floor mostly. The second floor is space for guests. The first floor is all public event space. That’s where the big beautiful space is, and the ground floor, which is really like a walkout basement, that’s where all the event staff have their offices. So it’s like living in an embassy where the ambassador has an apartment sitting on top of this big public space. I think that setup probably works best for people whose children are, either they don’t have kids or the kids are out of the house. I think it might be a little hard to raise kids in such a public environment, although our residential college heads do it with a kind of similar setup.

I will say that we’ve really enjoyed living in the house, and it makes hosting events really, really easy. We separate our lives, though, in the president’s house from the university. So for example, people are always shocked when they see me at the supermarket often on first thing Saturday mornings. That’s my shopping time. “Don’t you have someone who could shop?” No, no. I think not only don’t I have that, I don’t want that. I want to live in the world. I will say I do miss neighbors, and the house we own in New Haven is near Edgerton Park, and we know all our neighbors. We haven’t lived there for 10 years, and we’re looking forward to moving back in. We’ve had family members housesitting there for us for a decade, and I’ve evicted the nephews and nieces, and now we’re fixing things up and looking forward to living in a neighborhood again. Neighborhood,

Howard Forman: What about your recommendation for the next president? Would you tell him,

Harlan Krumholz: Or her, Howie!

Peter Salovey: Yeah. I would certainly say live in the president’s house and enjoy being so close to campus. Get out for a walk with your dog in the evening because even on days when people aren’t happy seeing you, they’re always happy seeing your dog. And Portia and Mandy have both had that experience on campus. And of course in times of campus emergency, it’s good to be close to the action. And I would say succession, it’s an interesting moment for me. I have very mixed feelings about it. Cognitively, I know that bringing someone in with new ideas is always important. Making a transition when the university’s in good shape, and we’re in good shape financially with the endowment, with the budget, we have a great leadership team. We have great deans, including Megan Ranney, and really the whole cabinet is very strong right now.

You want to bring, it’s time for succession in that sense. You want to bring a successor in who has wind at their back rather than at their face, and I think that makes the job much more attractive. Our campaign, which I will continue to work on right until we make our goal, we hit a milestone. Our goal is $7 billion. We have raised $5 billion as of the middle of summer. We’re probably around $5.3 billion right now. And so that’s going great. I’ll continue working on it. And personally, I just would like to do a little more teaching and a little more writing.

Howard Forman: That’s great.

Peter Salovey: Think about psychology, think about health, and think about leadership and policy, and do a little bit of writing about them, but emotionally it’s hard to let go. At a more personal level, I like to tell the story of Joe DiMaggio, who in his last year playing baseball for the Yankees, he was still batting .300. And this sounds a little self-glorifying, and I don’t mean to compare myself to Joe DiMaggio, but Joe DiMaggio when he announced his retirement, and a little kid said, “Say it ain’t so, Joe,” and Joe said something like, “It’s important to step away when people don’t want you to step away and don’t wait around until everyone wants you to step away.” I think there’s some wisdom there.

Harlan Krumholz: I want to say I think it’s wise what you’re doing, but yeah, you are indeed leaving at a time when people don’t want you to leave, and that is for sure true. And your contributions have been immense. I’ll put in one plug, people listening should know that what a pioneer you were and are in the areas of emotional intelligence. By the way, I think I always consider you a gifted investigator. Whenever you would give talks and sort of explain what your lab was doing and how you set up these experiments in sort of real-world settings. I was always sort of drawn to them. There’s one you were telling us about on the beach one time where....

Peter Salovey: Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. So it’s interesting. The lab did two things and one of them was looking at the effects of emotion on thinking and behavior, and that got us into emotional intelligence. The idea of emotional intelligence really came from our lab and we published the first scientific paper on it. And if you had asked me in 1990 when that paper came out, if 33 years, 34 years later, we’d still be talking about the idea, I would’ve said, “No, no.” But here we are still talking about the idea. I’m glad it resonated. The fact that the public was interested in it forced us to take it more seriously and really do a program of research over multiple decades around it. And then the health work. At the time, the health behavior work was really focused on, could we use principles from psychology to make messages more persuasive and then test whether those principles could work in the, were robust enough or strong enough to work in real field settings? So could we get people to buy sunscreen from a vendor at the beach?

Harlan Krumholz: Yeah, I remember that story.

Peter Salovey: People to go to the bodega in their neighborhood and buy a condom.

Harlan Krumholz: Yeah.

Peter Salovey: And we would set these very elaborate experiments up that would let us track behavior over long periods of time in response to multimedia campaigns based on psychological principles.

Harlan Krumholz: Well, they were so clever. My plug for you is, getting back to the emotional intelligence things, I think that we should be doubling down in the university about helping people to think about how they can acquire even better skills, not just our leaders. Of course, leaders need that, but throughout the entire university because it’s really that balance of other types of intelligence with the emotional intelligence leads to effectiveness and actually moving society forward. And I think that what you’ve done, there’s so much to do, but it’s also how do we amplify this in different settings? How do we help people gain the kind of skills so that it’s not that you were born a certain way, but you can actually build the skills to be able to be ever stronger in these areas. Anyway, that’s my plug to you. I think there’s a lot to be done, and I hope you’ll do that. I’m so appreciative that you came on today and appreciative for all your contributions over the years and your friendship really. Thank you so much—

Howard Forman: Me too.

Harlan Krumholz: ...for that.

Peter Salovey: Me too. Well, thank you both. Harlan, Howie, you are exemplars of the kinds of professors that create a more unified Yale and a more innovative Yale, and then you are accessible as individuals, and I know you champion accessibility in terms of getting people to Yale who might never have thought this was the kind of place they could be a part of. And I’m really, really very grateful. It’s what has made being president a true labor of love and a true honor, and it fills me with humility when I think about what a great institution this is. And so thank you for all that you do.

Howard Forman: Thank you very much.

Peter Salovey: Including hosting a podcast.

Howard Forman: Thank you. 100th episode.

Harlan Krumholz: This is Howie’s brainchild, Howie’s brainchild.

Peter Salovey: It’s not. It’s Harlan’s brainchild, but Harlan, take us home.

Harlan Krumholz: Okay. You’ve been listening to Health & Veritas with Harlan Krumholz and Howie Forman, and today with Peter Salovey.

Howard Forman: This has been a very special 100th episode, and we will be back at our regular time next week, but we always want to keep the conversation going, so please reach out via email at health.veritas@yale.edu to give us feedback or ask questions. Please rate us on Spotify, Google, or Apple Podcasts or wherever you find your podcasts.

Harlan Krumholz: And you can find us on social media. And increasingly we’re trying to broaden our reach, but also we’re still on Twitter or X where I’m at @HMKYale, that’s HMK, Yale.

Howard Forman: And I’m @theHowie, that’s at T-H-E-H-O-W-I-E.

Harlan Krumholz: Health & Veritas is produced with Yale School of Management and the Yale School of Public Health. Thanks to our researchers, these amazing students, Ines Gilles and Sophia Stumpf. Peter, I hope I can introduce you to them one day. They are amazing. We’ve had really great students help support us on the podcast and our producer, Miranda Shafer, who’s also just out of this world. And Peter, our 100th episode, we wanted to have you on. Thank you so much. Really appreciate it. Talk to you soon, Howard.

Peter Salovey: And it’s been a pleasure being with you, and thanks so much. Congratulations on the 100th episode.

Howard Forman: Thank you.

Harlan Krumholz: Thank you. Thank you.