What’s the Future for Western Businesses in Xi’s China?

At the Chinese Community Party’s 20th Party Congress this week, China officially extended Xi Jinping’s leadership for another five years. We asked Stephen Roach, a senior fellow at Yale Law School’s Paul Tsai China Center, what another term of Xi’s leadership means for China’s economic policies and the environment for Western businesses there.

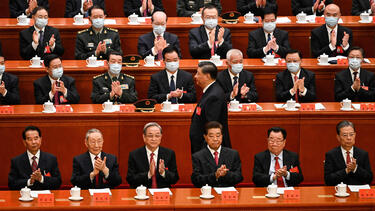

President Xi Jinping (standing) at the 20th Chinese Communist Party Congress in Beijing on October 16.

What is your main takeaway from China’s just completed 20th Party Congress?

Notwithstanding all the hype in the international news media over this once-every-five-year conclave of CCP (Chinese Communist Party) leaders, there was a notable lack of new news. Xi Jinping’s opening speech on October 16 was long on self-promotion and ideology, but actually about one hour shorter in terms of delivery time when compared with his grand oration five years earlier.

The language was steeped in dogma and generalities but the strategic thrust of his message was clear: China will stay the recent course—less market-driven and more state-directed, more muscular in terms of foreign policy rather than passive as Deng Xiaoping’s “hide and bide” would have implied, more self-reliant (especially with respect to innovation and technology), and steadfast in its resistance to unfriendly forces of containment (i.e., the United States) amid an increasingly treacherous global climate. Moreover, Xi doubled down on some of his most controversial policies—zero-Covid, property sector deleveraging, and income redistribution under the guise of a “Common Prosperity” campaign.

It’s not like these are trivial developments. It’s just that for a Xi-centric China that predictably has extended his leadership for at least another five years, most of these trends have now been in place for quite some time.

Where might Xi be most vulnerable in attempting to stay the course?

“If China is stymied in achieving self-reliance through indigenous innovation, all bets could be off on its longer-term objectives for economic growth and global leadership. Yet that is precisely the risk that is now evident.”

While there is a clear element of risk to virtually all of Xi’s strategic and policy pronouncements, the one that looms most problematic, in my opinion, is China’s commitment to advanced technologies as a linchpin of an important shift to indigenous innovation. If China is stymied in achieving self-reliance through indigenous innovation, all bets could be off on its longer-term objectives for economic growth and global leadership. Yet that is precisely the risk that is now evident in light of the Biden Administration’s recent rollout of unprecedented sanctions on leading-edge U.S. technology exports to China.

Intended as nothing short of a major chokehold on Chinese access to American made high-end AI and supercomputing chips, the new regulations put teeth into a September 16 warning shot fired by Jake Sullivan, U.S. national security advisor, who hinted at actions aimed at “a competitor [i.e, China] that is determined to overtake U.S. technological leadership.” It is hard to believe that the October 7 announcement of these actions coming on the eve of China’s 20th Party Congress was simply a coincidence. These export restrictions, in conjunction with the just enacted CHIPS and Science Act that provides $52.7 billion of industrial-policy support to the U.S. semiconductor industry, put a Xi-centric CCP on notice that the United States is taking dead aim on one of the key pillars of China’s great power objectives as a wannabe techno-superpower.

Is China likely to adopt a different posture toward Western businesses in a third term for Xi Jinping? How should U.S. companies respond?

In the past five years, the US and China have become embroiled in a trade war, a tech war, and now a new cold war. In my new book that is about to be published, Accidental Conflict: America, China, and the Clash of False Narratives (Yale University Press, November 2022), I argue that this ominous trajectory of conflict escalation wouldn't have occurred had it not been for the false narratives that both nations hold with respect to the other—leading examples being saving-short America’s “bilateral bluster” over a large trade deficit with China and a failed structural rebalancing of the Chinese economy that Beijing blames on America’s China containment strategy. Unless there is a more constructive turn of events in the direction of conflict resolution—and my book concludes with a three-part plan aimed at that objective —businesses in both nations will suffer.

Since 2018, every action that the US has taken against China on the trade and technology fronts has been countered by tit-for-tat retaliation by Beijing against American businesses. It is highly likely that the Biden Administration’s recent actions aimed at Chinese technology companies noted above will be followed by equally dramatic measures against U.S. companies. As a result, American multinationals operating in China— or drawing on support from China-centric supply chains—should be thinking long and hard about diversifying business risks away from excess dependence on Chinese markets and/ or China-related supply chain exposure.

What do you make of China’s surprising delay in the release of key economic data as the Party Congress got under way?

This was a dumb move in every sense of the word. Indefinitely delaying its long-scheduled October 18 GDP report just as the 20th Party Congress got going takes politicized CCP spin of a tightly censored system to a new low. Chinese economic growth was unusually weak in the first half of this year—recording average gains of just 2.6% on a year-over year basis in the first two quarters of 2022. Previewing the upcoming data, none other than Chinese Premier Li Keqiang, along with a senior official at the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), claimed “the economy rebounded significantly in the third quarter.” By failing to substantiate that claim with hard data—data that have long been under a cloud of suspicion on the best of days—the integrity of the Chinese statistical system has been dealt a near fatal blow.

Xi Jinping has been adamant in urging the Propaganda (or Publicity) Department to tell “a good Chinese story” aligned with the aspirational China Dream that he first espoused in late 2012. A data blackout in the midst of an important political event is a bad dream come true for any government’s statistical agency. Skeptics can hardly be blamed if they raise questions about subsequent reports of an eventual upturn in the data flow. For a long opaque and tightly censored China, this unfortunate incident is but the latest example of its uncanny knack for perpetually shooting itself in the foot. Maybe Chinese officials just don’t care anymore.