Design, Test, Spread

What kind of innovation does healthcare need? Nicolas Encina ’10 and his colleagues at Ariadne Labs have been demonstrating the potential of a collaborative, multidisciplinary process for designing and scaling simple improvements to healthcare—and also its limits.

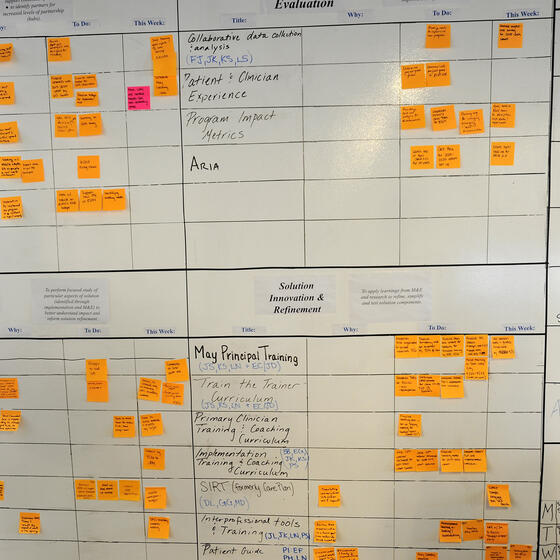

A scrum board at Ariadne Labs. Photo: Ted O'Callahan.

A 28-year-old expectant mother in the northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh arrived at a rural community health center in 2016; she was 40 weeks pregnant and bleeding severely. Realizing she needed emergency care beyond what the health center could deliver, birth attendants rightly referred her to the district hospital. The woman and her husband arrived at the hospital and discovered it was extremely busy. They waited but eventually decided to try a private hospital. By the time they reached that hospital, the woman needed a life-saving blood transfusion, but the blood bank was closed. The couple went on to another private hospital in a different district where she received the blood transfusion. But the obstetric nurses determined she also needed a C-section. Though the hospital was supposed to provide emergency care, there wasn’t a doctor available. The next day, as she was being transported by ambulance to the hospital in the capital, she died. The baby was never delivered.

The treatments to save that woman exist and were available. The health system failed to deliver those treatments.

Discussions about improving healthcare often focus on policy, aligning incentives, and who pays. Those are important discussions. Ideas about innovation in healthcare often focus on new drugs and novel treatments. Again, important things. But they may overlook simple, powerful ways to use innovation to improve healthcare and the systems that deliver it.

Stories about health system failures are not limited to India or developing countries; in the United States, 80% of the mothers who die around childbirth could be saved with known interventions. While the total number of deaths is comparatively small—roughly 700 to 900 each year—they are equally senseless, a failure to deliver on what we know how to do.

In total, around the world, every year 303,000 women die in pregnancy, childbirth, or the first six weeks postpartum. “If we delivered on the care that we know works, 99% of those deaths would be avoided,” said Katherine Semrau, an epidemiologist and director of the Better Birth Program at Ariadne Labs, in one of a series of conversations with Ariadne staff last year. There are an additional 2.6 million still births and 2.4 million neonatal deaths every year, of which about 80% could be prevented if known interventions were delivered.

Starting in 2014, Semrau, who is also a professor at Harvard Medical School, led one of the largest maternal health studies every conducted. The aim was to reduce the number of deaths of mothers and babies by increasing compliance with 18 essential birth practices outlined by the World Health Organization (WHO).

The organization where Semrau works, Ariadne Labs, describes itself as a health system innovation center. Atul Gawande, a surgeon, author, and New Yorker staff writer, founded the nonprofit in 2012. Explaining his rationale at the time, Gawande wrote, “The fundamental disease of the healthcare system is lack of execution. The cause is complexity.” Gawande still serves on Ariadne’s board as executive chairman.

It doesn’t take much looking to find evidence of that complexity. There are over 800,000 articles published each year in medical journals. The WHO’s 11th edition of the International Classification of Diseases, published in 2018, has 55,000 unique codes for diseases, conditions, syndromes, injuries, and causes of death—up from 14,000 codes in the previous edition. Healthcare delivery is not getting simpler.

Sometimes the treatment for complexity is innovation through simplicity rather than additional new gadgets. Gawande, working with the WHO and some 50 other experts around the world, developed a simple tool—a 19-item checklist—that helps surgical teams cut down on performance failures. The checklist was tested in eight hospitals around the world. The results, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, showed that the tool reduced complications by 35%; surgical deaths dropped by 47%. It has now been used in 362 million surgeries.

Ariadne Labs, a partnership of the Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, exists to create and scale more such tools. Ariadne’s projects touch on topics as varied as precision medicine, communication of medical errors to patients and families, and primary care models for developing countries. What they share is a focus on delivering evidence-based care to every patient every time. In the shorthand of Ariadne Labs, they work to close the “know-do gap.” In lay terms, they are taking on the challenge of getting human beings to execute on their training perfectly every single time whether the circumstances are mind-numbingly routine or chaotically complex.

“Most quality improvement is done through, basically, setting the expectation and doing training.”

The Know-Do Gap

In so much of life there’s what we know we should be doing, and what we actually do. In medical settings, it can be the difference between life and death. “We believe that if we could decrease the know-do gap, it would have more impact than any blockbuster drug or new technology,” said Evan Benjamin, Ariadne Labs’ chief medical officer.

In the U.S., healthcare account for nearly 20% of GDP. It’s a vast, complex industry under tremendous pressure to deliver state-of-the-art care while reducing ever-escalating costs. Too often in healthcare, the system itself is the problem.

For example, providers must perform something on the order of 180 tasks for each intensive care unit (ICU) patient every day. The timing and sequence is often critical. To prompt staff and warn them of sudden changes in a patient’s condition, the devices and machines sound alerts—according to a Johns Hopkins Hospital study, some 350 times a day from every single ICU bed. Intended to be helpful, the incessant alerts have morphed into a wolf-crying chorus too overwhelming to distinguish minor from critical. It’s impossible to not become desensitized.

This pattern, where healthcare systems become something to work around, is unfortunately common. Writing in the New York Times, Theresa Brown, a clinical faculty member at the University of Pittsburgh School of Nursing, called the American medical system one giant workaround, rife with operational failures. She describes nurses hiding drugs above the ceiling tiles in a hospital because of a perpetual pharmacy backlog. A second supply was the only way they could deliver reliable, timely care to their patients.

When alarm fatigue, snafus, and workarounds are the norm, why would we expect anything but failures of execution?

“We’re focusing in on creating better systems of care,” Benjamin says. “Most quality improvement is done through, basically, setting the expectation and doing training.” That approach doesn’t address the broader, interconnected aspects of the system required for care, so Ariadne is trying something new.

In some cases, the innovation Ariadne delivers is a discrete intervention, such as a checklist intended to improve communication, reliability, and teamwork. In others it means clarifying what is already known. “Sometimes, closing the know-do gap starts with making the performance of a health system visible with data,” Benjamin said. Ariadne Labs’ Primary Health Care Progression Model provides countries with standardized data on its primary healthcare capacity as well as resources for systematic improvement off that baseline.

Sometimes closing the know-do gap means simply having a conversation. Healthcare providers, patients, and families caught up in a serious illness don’t always have a frank discussion of priorities for the end of life. “With our Serious Illness Care program, we know how beneficial it is for patients to have a conversation with their clinicians about their hopes, values, and wishes. However, there are numerous barriers to having these conversations, so they don’t happen routinely or consistently,” Benjamin explained. “Our program provides system-level support so more clinicians and patients can have these important conversations earlier in the course of illness.”

The program includes training on how and when to have the difficult conversations—not something that is typically taught in medical school—as well as a system for documenting outcomes and a conversation guide to help clinicians develop expertise. Studies with oncology patients found reductions in anxiety and depression following the conversations. In addition, doctors had the discussions 2.4 months earlier and they were more comprehensive, patient centered, and focused on clarifying patients’ values, goals, and preferences.

“We’re seeking simple actionable solutions. It’s really easy to try to tackle a complicated problem with a complicated solution, but you have to have the discipline to say, ‘Fundamentally, what problem are we trying to solve?’”

Follow-through as Innovation

Benjamin made a distinction between breakthrough innovation and follow-through innovation. “I love those terms,” he said. “Breakthrough innovation is the creation of a whizzbang drug or technology. Follow-through innovation is how do you actually systematize the delivery of healthcare to get to high-reliability performance.”

An innovation that can provide a rigorous, reliable, discrete system improvement is enormously valuable. It takes sophisticated design to solve a complex problem with an elegant intervention. The degree of difficulty shoots up when it must be inserted into a complex existing workflow involving many people.

“We’re seeking simple actionable solutions,” said Nicolas Encina ’10, Ariadne’s chief science and technology officer and a graduate of Yale SOM’s MBA for Executives program. “It’s really easy to try to tackle a complicated problem with a complicated solution—trying to come up with this amazing technology or amazing platform—but you have to have the discipline to say, ‘Fundamentally, what problem are we trying to solve?’”

Ariadne Labs is a nonprofit—anything it copyrights is released with a Creative Commons license and is available to use and adapt free of charge—and it is shaping complete interventions, not standalone gadgets or apps. But, Encina noted, Ariadne’s approach is in essence an adapted version of a product development framework. “You have to ask the right question to start designing the right solution,” he said. “You need to be very agile, iterating a thousand times, then, finally, you get to, ‘Aha, this is it.’”

Ariadne Labs has developed a three-step formula for innovation: design, test, spread. “Everything we do here goes through a very similar process,” said Neel Shah, director of Ariadne Labs’ Delivery Decisions Initiative, “There are just a few building blocks.”

Design, Test, Spread

Six years ago, Shah, an obstetrician on the Harvard Medical School faculty, joined Ariadne Labs with an inchoate idea—to use the organization’s approach to improve outcomes for new mothers and babies. “My program really started with a blank sheet of paper. Now it’s at a place where we’re deploying solutions among tens of thousands of families across the country,” Shah said. The events in between offer one example of Ariadne’s innovation arc.

Shah started by devoting several months to surveying the landscape of maternity care over the last 50 years. One aspect of childbirth in the United States stood out as particularly amenable to Ariadne’s systems-focused approach: “C-section rates are all over the map in ways that make no medical sense.” At some hospitals, 7% of expectant mothers deliver via C-section; at others, 70% do. “It’s a full order of magnitude.” Existing research suggests 45% of C-sections are considered unnecessary in retrospect. These unnecessary surgeries introduce additional risk, create negative health consequences, and add an estimated $5 billion annually in healthcare costs over natural vaginal births in the U.S. Shah wanted to look at this disparity as a systems question. “What’s happening within hospitals that leads to such different outcomes for very similar people?”

Ariadne’s Design, Test, Spread framework opens up opportunities to take on complex issues, like this one, that are hard to get a handle on. “A lot of empirical thinking, which is the kind of thinking that goes into traditional research, requires highly structured problems,” said Shah. “But so much of what we’re trying to do is to try to bring structure to unstructured problems. And that’s really what design thinking is for.”

One important part of the design phase of research was suggested by Gawande, something familiar from his work as a journalist: talk to people. Shah said, “Atul told me to just go start visiting places and trying to figure out what they were doing differently—places with really high C-section rates, places with really low C-section rates.”

With a small team, Shah toured about a dozen facilities around the country for the initial overview. “There’s so much power in just showing up and absorbing things with your two eyeballs. It has driven pretty much everything that we’ve done since.”

As a result of the visits and the conversations with staff, Shah and his team built a rough roster of issues to explore. One emerged directly from walking through hospitals. “We realized that labor and delivery units are arbitrarily laid out. They’re so different from place to place,” Shah said. But those arbitrary decisions can have a direct impact on care. “We realized that managers’ decisions were constrained by the physical space. Of course, the spaces that we work in shape how we do our work.”

The next step was the test phase: a series of pilots. One was a collaboration with an architecture firm to document the impacts of facility design, not just in terms of convenience and patients’ comfort or even workflow efficiency but childbirth outcomes. The data revealed, “among other things, that hospitals with relatively more operating rooms and relatively fewer labor rooms tended to do more surgery,” per a write-up in the Harvard Business Review.

Based on that work, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Facility Guidelines Institute issued guidelines for best practices on facility management and design—the spread phase.

Architecture was not the only field that offered insight. “Managing a labor and delivery unit has a lot of the same challenges as running a hotel or a restaurant, though it is more safety critical,” Shah said. “A restaurant doesn’t know how many diners will show up on a given day or what they will order, yet the hospitality industry has tools for navigating the uncertainty.”

That understanding helped guide development of an admission decision aid to reduce the number of women prematurely admitted to a labor and delivery bed. Moving a patient to a bed too early adds costs and limits the ward’s flexibility. “Labor and delivery, just like an intensive care unit, requires having one nurse per patient during critical phases of labor,” Shah explained. “It’s much more staffing intensive than other parts of the hospital, with way more uncertainty. Eighty percent of the cost is staffing.”

The blank sheet of paper Shah started with has developed into a constellation of these and other projects under the Delivery Decisions Initiative. There’s a digital tool, based on quality data, to help women decide which childbirth facility would work for them. There’s a program that supports city-level initiatives to improve maternal health. And perhaps the most recognizably “Ariadne” effort, the Team Birth Project, uses “huddles” around a white board located in every laboring woman’s room as a way to ensure that the many people involved in a birth are on the same page. The white board, like a checklist, provides a shared reference in plain sight. The aim is to improve safety and to improve the experience. It is being piloted with hundreds of clinicians and thousands of patients at four community hospitals around the U.S.

“We deploy people to projects. They learn. They bring it back. They go to a different project. Professionally, they’re developing by seeing these different slices across healthcare.”

Collaboration

Collaboration is the organizational equivalent of family dinner. We know it’s a good idea to sit down for a meal every night, yet it often doesn’t happen. For Ariadne Labs, cross-disciplinary collaboration is the key to success, so the organization is structured to ensure that, in effect, nothing has higher priority than family dinner.

The organization provides three core platforms—Innovation, Science and Technology, and Implementation—that correspond to the design, test, and spread phases. Researchers like Shah—MDs and PhDs with deep expertise in a specific area of medicine—lead each project, guiding it through the Design, Test, Spread framework in collaboration with experts representing each platform.

“It’s a very collaborative model,” Semrau said. Those high-level collaborative interactions ensure that many perspectives influence how a problem is framed, a solution proposed and tested, and eventually how it is implemented and scaled.

Semrau said that the structure ensures constant touchpoints across the organization through brainstorming, scoping session, and interim check-ins. Leaders from each platform are present at key meetings throughout the project. That means relevant software that an epidemiologist or a surgeon wouldn’t know about is offered as a possibility. Or the experiment design used in another program is proposed as potentially applicable. And on and on.

For an academic researcher working in a traditional research setting, it may not be feasible to bring on a qualitative research specialist for a week or a month. The same is true of a statistician, a designer with expertise in user interfaces, an implementation expert, or a specialist in research methodologies.

At Ariadne it is the norm. Specialists from the innovation, science and technology, and implementation platforms will join a project for a specific task. They may be assigned to the project for days, weeks, months, or years depending on the need.

Encina explained that it’s all too easy for a principal investigator to get bogged down in administrative tasks, or to spend weeks trying to find a statistician or software engineer for a small piece of an overall project. “The more that we can systematize and create an engine around this process, it frees people up for doing the work they are expert at.”

Encina has launched and led startups that straddled science and technology, including, while a student at Yale SOM, co-founding Wingu, a SaaS data management and team collaboration platform for scientific workflow support. He also developed an innovation lab for PerkinElmer, an S&P 500 life sciences and technology company. Encina brought that expertise in structuring scientific innovation to Ariadne in 2017.

“We have amazing researchers,” Encina said. “I wasn’t going to come in and tell them how to do their work. I’ve focused on, how do you make this amazing group of scientists and technology people work really efficiently and effectively together?”

As with any organizational structure, there are tradeoffs. “In a siloed organization, everyone knows that so-and-so owns this, and they have to deliver it,” Encina said. “But the thinking is siloed, too. You don’t learn from other places.

“In the matrix environment, people are much more engaged. There’s cross pollination. But accountability tends to go down, because now you have 50 people in a meeting. Who owns what? By virtue of having so many people involved, you need to have more communication, which means more meetings.”

But the investment of time in a matrix structure and continual interdisciplinary collaboration has compounding benefits. “We see how current programs are benefiting from the work that we’ve done previously,” Encina said. “We deploy people to projects. They learn. They bring it back. They go to a different project. Professionally, they’re developing by seeing these different slices across healthcare.”

Similarly, as Ariadne team members worked with more and more partners, they started to recognize patterns. It became evident why one organization succeed where another struggled. That led to the development of a tool for assessing organizational readiness. If an organization isn’t quite where it wants to be, there are defined steps to improve capacity. Sometimes that might involve just the surgical teams that are adopting checklists, but more often an organization’s capacity depends on how the constituent parts coordinate.

When Are Systems Key to Solutions?

The WHO describes six critical elements to a healthcare system—workforce, service delivery, medical information databases, access to essential medications, leadership and governance, and financing. Each element has to be functioning and supporting the other five for the system to be effective.

The mother in Uttar Pradesh who died without ever receiving the care she needed was at the mercy of a system failure. The report Semrau’s Better Birth team released concluded, “Reducing maternal and neonatal deaths will require a comprehensive approach that addresses system complexity.”

The randomized control trial in Uttar Pradesh that Semrau ran, the one with 157,000 mother-infant pairs and 120 frontline healthcare facilities, illustrated how difficult this can be.

That large study measured whether the program would increase compliance with World Health Organization childbirth guidelines, but critically, it was also testing whether increased compliance reduced deaths. The results, published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2017, were a shock. Despite improvement in compliance with guidelines, there was no change to morbidity and mortality outcomes. “We all had tears when we first got the result,” Semrau said. “It was hard for everybody. We were disappointed that it didn’t have the impact that we thought it would.”

“In my previous work in academic settings, the study would have stopped there,” Semrau said. “It would have been a failure if we had stopped at the null result”—an outcome that doesn’t support the hypothesis being tested. “We try to dig deeper and ask more refined and nuanced questions about why we did not have an impact on morbidity and mortality.”

“One thing that I think we’ve learned is the impact and the importance of the connectivity across the health system.”

Semrau, with a team drawn from across Ariadne and partners in India, spent 18 months asking more questions. “It’s one of the things I am most proud of in my career,” she said. “We had 204 million data points across the study, so we were able to really come together—not just me and other epidemiologists but people who have experience with statistics, data management, anthropology, qualitative research, other quantitative research methods, as well as people who think about innovation and implementation pathways.” In 2019, they released a comprehensive report. “One thing that I think we’ve learned is the impact and the importance of the connectivity across the health system.”

Their analysis suggests it isn’t enough for providers to change practices if the system can’t support that work. “It’s not just about having the building blocks present,” Semrau said. “It’s about how they are either connected or not that makes a system function.”

The ability to collect and analyze so much data in the Better Birth study exposed fault lines in the health system. At the same time, it exposed the limits of existing research methods. “We measured a lot about the delivery volumes at the facilities. We measured the number of staff. We measured how many nighttime deliveries there were. How much oxytocin was used, and how much breastfeeding was initiated,” Semrau remembered. “But measuring management and leadership and teamwork—those ‘softer’ variables—is challenging.”

Beyond the disappointment of a null result, there’s an opportunity, Semrau said, to “make sure we’re measuring what’s really happening holistically in studies, interventions, and programs while they’re underway.”

Simple or Systems?

Can Ariadne Labs continue to focus on developing simple tools or is a shift to larger system questions necessary? According to Asaf Bitton, the organization’s executive director, the plan is a both/and approach.

Ariadne will continue to seek discrete decisive successes like the safe surgery checklist through the rapid cycles of innovation, prototyping, and testing. They expect some of those tools will cascade into widespread, impactful use. But some tools—as with the Better Birth protocols—may see uptake without creating the expected impact. In those cases, Bitton said, Ariadne will patiently move upstream to work on system factors.

“As you embed yourself deeper and deeper into systems improvement, you realize that you can’t just focus on the tool side,” Bitton said. “You also have to look at the system side, which requires medium- and long-term engagement.”