Can Mobile Money Boost Financial Inclusion in Southern Africa?

Mobile money offers opportunities for the unbanked to save, spend, and transfer money using just a cell phone. Linda Du ’19, an MBA student at Yale SOM, traveled to Zambia, Malawi and Mozambique to talk with providers, customers, and others about the technology’s potential to give the poor access to the financial system.

LInda Du

Matilda is a mother of three living in rural Malawi who runs a small fritter business. She fries donuts in her home in the early hours and then sells them by the side of the road. She doesn’t know how to read or write, and her financial needs are not served by traditional banks, which are discouraged by the relatively high costs and low transaction volumes of banking for rural populations.

Nevertheless, Matilda is part of the financial system. Microloan Foundation Malawi, a microfinance institute, serves her credit needs for her business. For her savings, Matilda turns to Airtel, a mobile network operator (MNO).

Mobile money enables anyone with a phone and a SIM card to complete basic financial transactions such as savings and transfers without having a bank account. The model was pioneered in East Africa, most notably by Safaricom’s M-Pesa in Kenya, and has quickly spread to other parts of the developing world. It usually involves the agent banking model, a network of agents with kiosks who can reach far-flung rural populations at a lower cost than brick-and-mortar banks. If Matilda wants to save some money from her business, she walks to her nearest Airtel Money kiosk with her cash and mobile phone, and although she cannot read, the teller can help her make a deposit as small as 50 MWK (7 cents in U.S. dollars), linked to her SIM card.

Over the first six months of 2018, I traveled in the three neighboring Southern African countries of Zambia, Malawi, and Mozambique, exploring the scope of mobile money services. I chose to focus on these countries because their mobile money adoption levels fall around the median of Southern African levels—Zimbabwe has the highest rate of penetration at 49% and South Africa the lowest at 19%. They are fairly representative of the diversity of the wider region, with Zambia and Malawi being former English colonies and Mozambique being a former Portuguese colony. And finally, interest in regional collaboration efforts has grown as initiatives for a Zambia Malawi Mozambique Growth Triangle (ZMM-GT) are revitalized.

I conducted field interviews with experts in international development including practitioners and professors, customers like Matilda, regulators including banks and ICT authorities, and mobile money service providers. I set out to understand how the environment for doing business in mobile money in these three countries differed, and how it might be improved to allow technological innovations to take hold.

The Current State of Mobile Money in Zambia, Malawi, and Mozambique

Market Indicators and Maturity

Below, key indicators relating to the infrastructure required for mobile money to be successful are compared in the three Southern African countries of Zambia, Malawi, and Mozambique, and benchmarked against Kenya. At first glance, Zambia appears to be closest to Kenya on these key indicators, with a relatively high GDP and strong mobile penetration. However, there’s a key difference: population density. Population density matters, because it makes it more difficult for both communications and financial infrastructure to reach sparsely populated expanses of land. This is a key challenge for both Zambia and Mozambique.

|

Zambia |

Malawi |

Mozambique |

Kenya |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Population, total (millions) |

17.1 |

18.6 |

29.7 |

49.7 |

|

Population density (people per sq. km of land area) |

23 |

198 |

38 |

87 |

|

GDP per person employed (constant 2011 PPP $) |

9490 |

2646 |

3428 |

8521 |

|

Commercial bank branches (per 100,000 adults) |

4.7 |

3.2 |

4.1 |

5.7 |

|

Automated teller machines (ATMs) (per 100,000 adults) |

10.9 |

4.9 |

10.3 |

9.8 |

|

Mobile cellular subscriptions (per 100 people) |

72.4 |

39.7 |

52.1 |

80.43 |

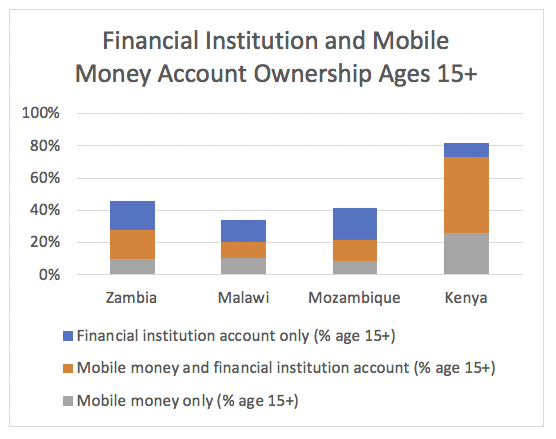

The mobile money sector in Southern Africa is, in general, less mature than in Eastern Africa, particularly when compared to Kenya, the pioneer of mobile money. In Zambia, Malawi, and Mozambique, an average of 23% of the population holds a mobile money account, compared to 73% of the population in Kenya. In total, there are around 19 times as many mobile customers in East Africa compared to Southern Africa. However, the growth rate in Southern Africa, measured by number of new mobile money accounts, is twice as fast, with 29% year-on-year growth in 2015-2016. Opportunities for the development of mobile money in Southern Africa abound as the market starts to mature.

Competition

Financial behavior, market structures, and consumer demand vary widely in the three countries, leading to different competitive landscapes. For mobile network operators (MNOs), competition in mobile money is viewed as an extension of the long-running battle of telecommunications services. The challenging competitive landscape can be illustrated by the fact that no single player is dominant in all three countries. For example, Zambia’s mobile money sector is dominated by three companies, MTN, Airtel, and Zoona. None of these three companies is currently offering mobile money in Mozambique, where Vodacom M-Pesa dominates.

Mobile money services in Southern Africa have been championed by mobile network operators (MNOs) including Airtel, MTN, and Vodacom. Kavir Bhoola, head of strategy for Market Area Middle East and Africa at Ericsson, explained to me why MNOs have a strategic advantage in mobile money compared to banks and third parties: “MNOs have a higher existing subscriber base which enables them to quickly reach a large market. Mobile money as a product has synergies with the telecommunications platform and established network that MNOs already have.” MNOs in these markets leverage their expertise in running networks of agents, who have been reselling airtime vouchers to customers for years, as well as their brand recognition.

Recognizing the opportunity that this model of banking presents, traditional banks in the region are also entering the market through the agent banking channel, building agent networks to serve more customer segments and reach greater geographical areas. For example, Zanaco in Zambia launched an agent banking model called Xpress in 2017, and Opportunity Bank Malawi announced in 2016 that it would reduce brick-and-mortar bank services to focus on agent banking.

A third type of non-bank financial institution is independent of MNOs and traditional banks. For example, Zoona is focused on mobile money, operating in Zambia and Malawi.

Opportunities for Mobile Money to Make an Impact

Economic Perspective

I interviewed Mushfiq Mobarak, professor of economics at Yale SOM and co-chair of the Urban Services Initiative at the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab, to understand the impact that mobile money can make in the framework of development economics. Mobarak said that there are opportunities for mobile money to create an impact in emerging markets within the context of four specific market failures:

- Transfers: Mobile money can improve the efficiency, speed, and security of person-to-person transfers. In the context of migration, Mobarak imagines that mobile money remittances might reduce the frequency at which migrant workers need to return home.

- Insurance: When low-income workers experience incidents such as health shocks, natural disasters, and other emergencies, they often do not have formal insurance and therefore experience grave income shocks. Such workers often rely on informal risk-sharing, providing gifts and transfers within their social networks to those who experience such shocks. Mobile money could reduce the response time for people to respond to emergencies in their networks.

- Savings: Security of savings is increased, as mobile money provides a secure and accessible means of saving money.

- Credit: Limited access to credit is a constraint faced by many people in the developing world. While it is currently a nascent and experimental field, mobile money can provide the technology platform for additional financial services, including microcredit.

Societal Perspective

Mobile money has already advanced financial inclusion to the developing world. The low cost of propagating the agent network model means that more geographical areas can be reached, and low savings and transaction sizes can be served. Low-income populations whose savings, loan and transaction sizes are not served by traditional brick-and-mortar banks can easily open a mobile money account with only a SIM card. They can securely save and transfer money, rather than hiding money or sending it across the country via bus drivers.

Various NGOs have recognized the potential of mobile money to advance financial inclusion in developing countries. Financial inclusion is seen as an enabler for 8 of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The United Nations Capital Development Fund (UNCDF) has created a program called Mobile Money for the Poor (MM4P) dedicated to advancing digital financial services in the UN-classified Least Developed Countries (LDCs). MM4P supports market development programs for digital finance ecosystems in the countries it works in, and provides financial, technical and policy assistance.

Catherine Highet is the technology lead at the Women’s Financial Inclusion Community of Practice at the World Bank Group’s Consultative Group to Assist the Poor (CGAP), a consortium of more than 30 organizations that works to advance financial inclusion. Highet pointed out that women in the developing world are often time-poor, with a wide range of responsibilities. Mobile money can bring them greater financial inclusion. “Spending half a day traveling to the city and waiting in line to pay for electricity costs women precious time,” she said. “Mobile money can alleviate some of these challenges, allowing women to make secure financial transaction, when and where it suits them best.”

The franchise model that agent banking uses also creates employment opportunities, especially for young people. Serving as agents creates a culture of entrepreneurship and financial independence.

Another potential area for societal impact: some mobile money companies offer financial management education to customers, which has the dual benefit of helping customers to achieve financial resilience and encouraging savings with the company.

Business Perspective

Mobile money can also be profitable for the firms offering it. For MNOs, mobile money offers a diversification opportunity from traditional communications services, as well as a cross-selling opportunity as customers can complete monetary transactions and buy airtime at the same place. Ericsson’s Kavir Bhoola explained why mobile money is attractive to MNOs: “Mobile money offers operators the chance to tap into a new revenue stream within an organized network with limited infrastructure.”

An analysis by the mobile industry group GSMA on the profitability of mobile money for MNOs finds that once a mobile money venture becomes mature and ecosystem-based, it can contribute over 15% of the MNO’s total revenues. Agent banking offers MNOs and banks the opportunity to open new market and customer segments and capture more value from them. McKinsey estimates that digital financial services, which encompass mobile money platforms, still have the potential to reach 1.6 billion new customers in developing markets.

Mobile money can also have positive ecosystem effects, making business easier for third parties by simplifying payments. In many Southern African countries, it’s possible to make mobile bill payments for utilities and cable TV, increasing access to those services and creating joint revenue streams.

East Africa provides examples of how mobile money can catalyze new businesses and even new technologies. For example, the Kenyan company M-Kopa used mobile payments to introduce innovative financing plans for solar panels.

Obstacles Limiting the Growth of the Mobile Money Sector

Regulatory

The Southern African mobile money market is much less mature than in East Africa, and regulators often struggle to keep up with innovation. Regulation can be complex, with multiple regulatory parties involved, depending on the type of organization that is offering the service. In Zambia, mobile money offered by MNOs is regulated by the ICT authority (ZICTA), as well as the Zambian Central Bank.

Regulation of mobile money can be further complicated by licensing issues. Banks often hold full banking licenses, which enable them to provide more products and services through agent banking, but also subjects them to more scrutiny. MNOs and other non-bank financial institutions often hold licenses only to offer specific services, which can limit their product and service offerings.

As a 2010 GSMA discussion paper points out, the digital and traceable nature of mobile money makes it less susceptible to money laundering than cash and suggests that anti-money-laudering (AML) systems should be seen as complementary to financial inclusion due to their role in safeguarding the informal financial sector in a country. While it is still necessary to set standards for AML and know your customer (KYC) in the mobile money context, these processes should avoid excluding customers.

When KYC processes have strict rules on identification validation, lack of formal identification can prevent customers from opening mobile money accounts. Malawi, for example, only introduced its official national identity program two years ago in 2016, and while uptake has been rapid, national registration cards are far from ubiquitous. Mobile money providers in Malawi therefore allow a degree of flexibility when it comes to customer identification, allowing voter registration cards to be used. Regulators also need to consider consumer protection; many mobile money customers lack financial education and are vulnerable to misconduct and abuse. A CGAP blog post highlights risks to consumers of digital financial services, including fraud and data theft.

Operational

Operational issues, including discontinuities in product offerings, often result from these regulatory issues. For example, Mozambican banks can hypothetically offer microcredit through agent banking because they have full banking licenses, but their agent banking networks are considerably weaker than those of MNOs partly because they are subject to higher degree of regulation by the central bank. Agent liquidity has been identified as another operational challenge: many agents often do not have enough float to serve all their customers. Many customers are bounced, and the proportion of bounced customers is higher for mobile money than for traditional banking. In Zambia, a survey of agents by Mobile Money for the Poor (MM4P), found that on average each agent bounced nine customers per day, leading to lost income. Research from CGAP found that for many agents, the cost of liquidity management was the greatest operational cost.

Infrastructure also limits mobile money service providers’ growth. Telecommunications infrastructure remains underdeveloped, especially in Zambia and Mozambique, whose size means that rural mobile network coverage, essential to the functioning of mobile money, is not always assured. Gulamo Nabi, managing director of Vodacom M-Pesa Mozambique, mentioned in an interview that geographic expansion of agent networks is also limited by traditional brick-and-mortar banking infrastructure for liquidity management, as agents still need to be situated near banks or “super-agents” with agent-to-agent transfer capabilities to balance their floats. In Mozambique, a country with a large land area and low population density outside of Maputo, mobile money is still much more prevalent in the urban setting than in rural settings.

Social

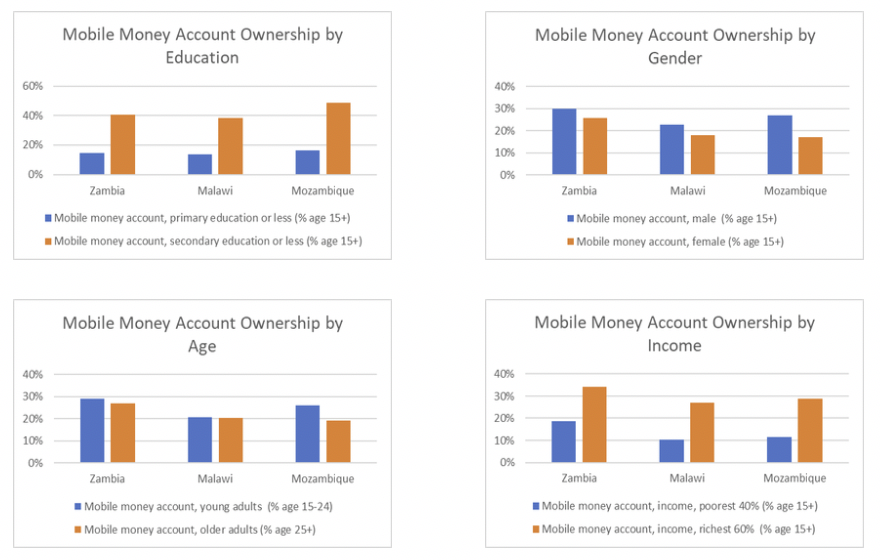

Another industry-wide issue is that mobile money may not be contributing to financial inclusion of disadvantaged groups. Despite its potential benefits for the poor, mobile money technology may magnify rather than diminish incumbent social structures. The use of mobile money skews towards educated, male, young, and high-income customers. GSMA found that while mobile money may be helping to close the gap between men and women, the global proportion of women holding a mobile money account remains low, at 36% (the proportion varies by deployment from 15% to 50%). In Zambia, Malawi and Mozambique, the gender gap in mobile money account ownership is smaller, at 7% on average.

A study by FSD Zambia found that barriers to women’s financial inclusion on the supply-side included accessibility, affordability, and appropriateness. On the demand side, gender norms, customs, and culture are cited as limiting women’s financial empowerment.

These limits mean that the growth of mobile money risks further marginalizing of low-income and low-education populations. But there are opportunities to close the financial inclusion gap as the market for mobile money grows.

Strategies for Creating a Landscape of Innovation

Creating a landscape for innovation, and ensuring that mobile money is inclusive of marginalized populations, will require a great degree of cooperation. The mobile money sector should be viewed as an ecosystem rather than a battleground so that consumers and service providers can extract maximum value from the technology. That is, rather than viewing each other as competitors, MNOs and banks should recognize that partnerships can deliver substantial value from taking advantage of licensing, expertise and agent networks to deliver new types of products and services through established networks: currently, no single organization has the capacity to provide an end-to-end mobile money service.

One key is interoperability, the ability for mobile money operators to connect to each other and the banking system. Regulators can set standards for interoperability to enable a stronger ecosystem. One example of strong interoperability is Barclays Zambia’s Bank to Wallet service, which lets Barclays customers move money from their bank account to their MTN Momo Wallet. Integrating with other services sets businesses apart: in GSMA’s analysis of mobile money businesses, the most successful companies were the most integrated and served as a platform for a wide payments ecosystem between banks, billers, organizations for bulk disbursements, and merchants. The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation says that interoperability may be the most important condition for pro-poor payment systems; the organization recently released open-source software that it hopes will become “a reference model for payment interoperability between banks and other providers across a country’s economy.”

Esselina Macome and Silvio Chiau of FSDMoç, a facility for financial sector development in Mozambique, suggest that to enable free and fair competition between bank and non-bank financial services, regulators can regulate by service, rather than by the type of organization offering the service, thus enabling greater flexibility to banks and MNOs to choose different operating models, products, and services without being limited by licenses. To stimulate innovation, regulators can also enable “sandboxes” so that service providers can experiment with new products and services without being subject to strict regulation, and authorities have foresight when it comes to how to regulate new offerings. In May 2018, FSDMoç launched a Sandbox Incubator project for new financial technologies. The incubator enables a touchpoint between the regulator (Bank of Mozambique) and providers to develop, test, and demonstrate new products in a supervised environment.

Mobile money organizations can ensure resilient agent networks by treating agent management as talent management and committing to train agents. HR policies designed to retain and reward highly performing agents can increase agent loyalty and improve business performance. I met a number of mobile money agents across Zambia and Malawi, usually young and often female, all sharing an entrepreneurial instinct. I was thoroughly impressed by one young woman who managed numerous kiosks in Lusaka and was using the profits from her business to propel her through nursing school.

The relationship between agent and mobile money organization is often mutually beneficial. Successful agents who provide excellent customer satisfaction help to build brand loyalty while making greater commission-based profits. The nursing school student and mobile money agent I met was honored to be recognized as an outstanding agent by the organization, and grateful for the opportunities to train and expand her business to more and more kiosks. Companies can also provide better operational support to agents—for example, by using microcredit partnerships to provide a credit line to agents. To address the challenge of agent liquidity, the microcredit organization FINCA International has investigated opportunities to create push-pull accounts for Airtel and MTN mobile money agents in Zambia, allowing them to take out credit for their operations when needed and to rebalance their FINCA accounts from a phone. GSMA found that agent training and monitoring not only enhance customer experience and loyalty, but also serve as the first line of defense against fraud and other abuses. A well-trained and consistent agent network can therefore become a key competitive advantage for mobile money organizations.

Those designing mobile money products and services must design to the specific needs of marginalized consumers, who have sometimes overlapping but often disparate needs. Design thinking, which urges designers to create user-friendly products and to engage in thorough customer research, is becoming commonplace in the financial inclusion arena. At the ICT for Development Conference in Zambia this year, “human centered design” was the focus of many workshops and presentations.

At the conference, UNCDF’s Mobile Money for the Poor (MM4P) program presented its work with the design agency 17 Triggers and other organizations involved with digital financial services, in a workshop that focused on designing financial products to meet the specific needs of Zambian mothers. The group chose this segment because when women control finances, the whole family benefits. Catherine Highet told me that women are far more selective customers than men globally, quoting the head of retail at Kenya Commercial Bank, who said, “If you meet women’s needs, you will exceed men’s expectations.” She said that she urges firms to explore community power dynamics, social norms, and enabling forces for women’s use of digital financial services. They should bring men into the conversation, as they are gatekeepers and can become advocates once they are engaged. When it comes to regulators, she said, they “need to remember that identity, movement and access, basic and technical literacy are all areas that can disproportionately limit a woman’s ability to access and use a mobile phone, and areas that a regulator can influence. “

Conclusion

In Zambia, Malawi, and Mozambique, mobile money helps to create better futures for customers and agents. It provides tools for Matilda, the mother of three with a fritter business, to save for school fees for her children. It provides training and employment for the agent who doubles as a nursing student, and for the tellers she employs. In an ideal future, every person in the world will have access to the financial services they need to create a sense of security for themselves. Mobile money can be an effective tool in advancing economic development when it is profitable, sustainable, and inclusive. However, we must remember that as a tool, it has its limitations. For financial inclusion to be truly pervasive, a holistic strategy including social change, innovative thinking, and regulatory considerations must be pursued, so mobile money diminishes existing inequalities of financial access rather than augmenting them.