What Can We Learn from Trump?

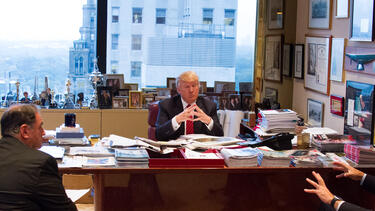

What to make of the rise of Donald Trump in the contest for the Republican presidential nomination? Is it a story of leadership capability transcending sector? Is it primarily one about disaffection with professional politicians? Or is it a yet-to-be-completed morality tale about the power of celebrity in a fame-besotted world? Leadership scholar Jeffrey Sonnenfeld and political scientist Jacob Hacker recently sat down for an hour-long conversation with Trump and discussed their impressions of the man and the current moment in political history.

Read Sonnenfeld’s account of the interview in Fortune magazine.

Q: You study politics and leadership. Donald Trump is right now at the center of discussion in those fields. Is there something you take away from meeting someone like that in person and seeing the differences between the actual human being and the various projections?

Jeffrey Sonnenfeld: You absolutely do. You see somebody who is selling an image. I would say that is a core aspect of leadership that you see across many fields, whether it’s Sam Zell, who elected to create an image of the rebel without a cause look of the 1950s, versus the Averell Harriman look for Steve Schwarzman. I don’t really think that Tommy spends a lot of time in the hood, or Ralph really plays polo. And Martha, when you get to the backstage of her true life, she’s hardly the doyenne of domestic tranquility. But they all create an image.

Trump is masterful at creating what that image is, and living that life, and he knows that it doesn’t just happen on its own. You need to fuel it.

It’s something that Jimmy Carter never understood—as a virtue and as a failing. As a virtue, there was a certain humility about Carter with the people’s inauguration and carrying his own bags. A lot of folks wanted the kind of aura that Ronald Reagan projected. They want the sense of heroic stature, a leader who projects an image larger than the rest of us. We hope that they know something we don’t know.

Trump projects a notion of, I’m in charge, I know what’s going on, you can relax. Nobody ever called Alexander III of Macedonia “Alexander the Great” until he and his mother invented that whole false lineage to Achilles and Zeus. And Trump somehow instinctively knows that working that image is a critical part of leadership.

And it’s a studied maneuver. He is a very disarming personality up close. This will sound like a paradox, but despite all the bravado and grandiosity, there is an authenticity about him when you speak to him in person. He clearly wants to make an impression on everybody, but he cares to know if it works. A truly arrogant person is not that attentive to the audience.

You can feel it in the building, you see it in the elevators, see it in the people that work with him, that they’re all proud to be there. They carry themselves with a sense of mission. He makes them all feel important. It’s quite different than the persona on his now-gone TV show, where he would sit there frowning, lower lip protruding, with that skeptical, show-me attitude. That’s anything but the reality of who he is.

Jacob Hacker: One of the things about Trump is that he’s really a politician, even before he seriously entered into politics.

Sonnenfeld: That’s a really good point.

Hacker: And that is the essence of politics. It’s performance as well as authenticity and policy. And Trump is well versed in presenting an image of himself.

I think we should all have a big reality check about his likelihood of winning the nomination, which I would still say is pretty low. But what’s striking to me is the extent to which his very lack of scriptedness, and the degree of grandiosity in his campaign, and actually, the offensive things he sometimes says, have all been interpreted as a sign of his genuineness and his fitness for office at a time when there’s a sense that politicians are distanced from reality, and not willing to say what they believe.

Sonnenfeld: I think that’s a huge point. What Trump does in speaking so candidly is demonstrate that he’s not over-managed by platoons of public relations staffs. It’s just the same with corporate leaders—you don’t know what they think anymore. So much gets scripted by way too many handlers.

The question is, do we need that professionalism? Do we need all those handlers? When I see CEOs that do well motivating their troops in good times, introducing new products in times of threshold and transition, or in times of adversity, in a crisis, it’s not when they’re reading off a teleprompter, but it’s when they’re listening and answering questions, like Trump did with us today.

Hacker: Yes. But we need candidates who have policy positions grounded in evidence and who have thought seriously about challenges of public leadership. And so far Trump really does not have many established positions. Most of his policy platform is around immigration, where his position is both completely unrealistic and completely offensive.

He has so far benefited enormously from the fact that he’s the story himself. And the degree of press coverage of him is truly remarkable. He basically is getting more coverage than all the other Republican candidates combined.

The people who study politics know that the odds are very much against him. But I do think he’s likely going to have a big effect on the Republicans. Initially his effect has been to push many of the other leaders to the right on immigration, Scott Walker most notably.

Sonnenfeld: And now a progressive position on taxation.

Hacker: Yes. It’s clear that he has not bought into the tax cut orthodoxy of the party, that he thinks the carried interest provision that allows hedge fund managers to pay capital gains tax rates on the income they get from managing other people’s money is not a great idea. And Jeb Bush has come out with a tax plan that, while containing massive tax cuts mostly benefiting those in the upper reaches of income distribution, also does end the carried interest provision.

And Trump claimed in this conversation that he didn’t think that Bush would have taken that stance had Trump not come out against the carried interest provision first.

I think what is striking about Trump’s candidacy is the extent to which he is so at odds with the Republican establishment and elements of Republican orthodoxy. It’s not that surprising that Donald Trump doesn’t care what Karl Rove—whom he called a “moron” in our conversation—thinks. What is surprising is that a lot of Republican voters don’t seem to care about that orthodoxy as much as we might have thought.

He said he thinks super PACs are ridiculous, and he’s right. He rightly points out that it’s a pure fiction that these big pockets of money coming mostly from ultra-rich supporters are not coordinated by the campaigns.

He did emphasize transparency and question the super PAC system, and in that respect he’s, again, much more forthright about the need for change than any of the other Republicans in the race.

Sonnenfeld: I think he has a very sensible and powerful position on the importance of transparency. And it is absolutely not Republican Party doctrine, and it’s not popular in part of the Democratic Party.

Q: So he’s able to break these rules, whether of party orthodoxy or what everybody says you’re allowed to do on a campaign. Why is he able to get away with it?

Hacker: I think there are a number of factors. One is that he is a true celebrity, and another is that we are still at an early stage of the campaign. Let us not forget that we’ve had candidates who crashed and burned after the early primaries. Steve Forbes, we all forget, ran for president at one point, and actually did well in some early contests.

So there’s partly just this huge amount of news coverage, fascination with Trump as a figure, the feeling that he’s refreshingly honest. When I talk to people about him, they all say that he says what he feels. He’s not politically correct. He’s not following talking points.

It’s striking that we’ve gotten to a point in our political system, ironically, where a billionaire—whether $1, $2 billion, depending on who you listen to—looks more independent than somebody who’s beholden to a few billionaires who are donating to their campaign.

Sonnenfeld: That’s an advantage of a successful business leader. This is something that Thorstein Veblen pointed out a century ago in The Theory of the Leisure Class, which you could take up right through Robin Leach’s Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous. There’s always been a fascination with those who succeed in this system. We don’t like people who cheat to get ahead, but if it seems like it’s honest hard work, and maybe innovation, the American public tends to admire it and want to emulate it.

Hacker: Another part of the reason why people are drawn to him is that he presents an image, not of a kind of superhuman, successful businessman, but of someone who’s recovered from setbacks, and who’s shown the sort of pluckiness that the United States values.

It is worth noting that the U.S. is far more forgiving with regard to bankruptcy than almost any other rich nation. He has availed himself of second chances, and is more popular for it.

Sonnenfeld: People find it very inspiring how he fights back—both when he’s attacked and when he has faced adversity.

So I think that triumph over adversity is a great business leader quality. I also think that his very hands-on style, that he defies bureaucracy, is something that many take-charge, hands-on, roll-up-the-sleeves business leaders can bring, as opposed to those who are over-scripted, manicured, and distant from their business.

Hacker: But I think it’s worth noting that while he has made a large amount of money and lost a large amount of money, he has also benefited enormously from his background. He inherited a very large amount from his father, Fred. He has also benefited from government in a way that may not be readily acknowledged by many of those who valorize his achievements.

His father apparently very much benefited from the Federal Housing Administration, and some real estate deals that depended heavily on the public sector. And Donald Trump himself talked about working with the government and community boards. No one builds real estate in Manhattan without having a relationship with government.

I would be curious to hear what he would say about what the right relationship should be between business and government. I do think it would be nice if the Republican Party could move beyond seeing every form of business-government interaction as either crony capitalism or supporting the job creators. It seems to me that on a lot of issues, from climate change to dealing with inequality and insecurity, we need to have a stronger partnership between business and government—not the kinds of partnerships that you usually see hauled out as examples, like contracting with some private sector entity to do something, but the larger partnership of seeing business and government as being in constructive tension with each other, rather than at constant war.

One other topic we discussed with him was the inheritance tax. He certainly isn’t willing to give up on the Republican position that the inheritance tax should be called the “death tax” and is an abomination. But he didn’t really bat an eye when I said, “If we don’t have an inheritance tax, we don’t tax accumulated capital gains, and we basically step up the value of the estates and let people inherit them tax free.” And he said, “Well, that’s a problem we’ll have to deal with.”

Sometimes with Trump it seems that his solution to all these really difficult, thorny issues that have defied resolution for decades is simply to get someone like Donald Trump to negotiate hard. Without in any way diminishing his achievements, the reality is that we have some really big structural problems in American politics today.

We have two very polarized parties, and we have a political system that is set up in ways, with the separation of powers, that it’s pretty hard for it to operate effectively when you have the parties this far apart, and especially when you have one party, the Republican Party, that has over the last 15 or 20 years adopted an incredibly anti-government stance that is both anti-government on policy and anti-government on procedure, willing to sort of tear down government institutions to win political fights.

It seems to me the biggest contribution that Trump could make would be to push back against this idea that we should be divided on all these issues into these really neat boxes that involve fealty to the most conservative position on social issues and the most conservative position on tax issues and the most conservative position on financial issues, on the one hand, or the most liberal positions, on the other hand. Instead, we should be thinking much more about how to govern a complex nation and deal with some of the challenges we face, which is inevitably going to require a mix of ideas from across the political spectrum.

That could be a great contribution. I’m afraid what it might do is fortify the Republican establishment into believing that the real solution is to stop Donald Trump at all costs, rather than reconsider its hardest-core positions.

Sonnenfeld: Well, he’s a threat to all established factions of the Republican Party.

Q: Jacob, you mentioned that it’s important to be realistic about his chances. What milestones would you look at to judge whether his chances become greater over time?

Hacker: He’s clearly a very strong candidate in terms of polling right now, but it’s very early in the race, and indeed, all the national polling and state-level polling right now isn’t going to speak very well to who’s going to win. It’s much better at telling us what the pros and cons of different candidates are and what groups they appeal to.

Trump has out-survived everyone’s expectations so far, and I suspect that he will continue to hold a strong position into early next year. I think the big test for him will be the early primaries.

And it’s worth noting that New Hampshire and Iowa are both contests that rely a lot on the ground game. And though he does actually have a campaign organization at this point, he does not have anything like the organization in the field that, say, Jeb Bush does.

This is a very unusual campaign on the Republican side, because we have so many credible candidates. And that has been a significant advantage for Trump in two respects. One is that they’re just dividing all of the attention and the poll results right now, so that there’s no coalescence around an alternative. It’s also the case that someone who speaks the way Trump does, clearly, plainly, sometimes offensively, just really stands out from the scattered statements that one is going to hear from any of the other candidates.

Sonnenfeld: A lot should be sorted out, like you say, with New Hampshire. We’ll probably see a large number of the campaigns collapse like lawn chairs by then. You have donors who become disaffected and demoralized.

Hacker: This is an odd period in our politics as well, because not only are there so many Republicans, but there are so many billionaires out there willing to bankroll Republicans. And so one question is, to what extent will the Republicans who are low in the polls and who are not really winning delegates drop out? That will depend in part on whether or not their deep-pocketed supporters are willing to accept the reality and also to side with the establishment and back a clear alternative to Donald Trump.

Q: How do both of you think about your role as scholars and when you should enter into the contemporaneous political discussion? When do you decide it’s an appropriate time or appropriate issue to be talking about, to be sharing your work?

Hacker: To be absolutely clear, I’m not signing up for the Donald Trump campaign. I appreciate that he gave us the chance to ask tough questions, but I came here as an interviewer, not an adviser.

Sonnenfeld: I’m not making an endorsement, either.

Hacker: I have advised candidates in the past. I think it’s very important to distinguish between sharing your research and its implications and your considered judgment on issues with candidates or people in public office, on the one hand, and becoming deeply engaged with politics as a scholar, on the other.

I think there are times when you need to do the latter. In fact, when the healthcare reform debate was taking place, I spent a lot of time working on health policy issues in Washington, and I certainly was sharing work and research that I’d done, but I was also an advocate for an outcome, and a strong one.

And I think that is an appropriate role for scholars to play when their research speaks to important public problems. But I don’t think we should pretend that there aren’t risks that are associated with playing that role.

And to me, it’s too bad that we don’t have more cases in which people who are doing research on issues and are really knowledgeable are willing and able to take their results to public officials and even press them on those issues. That’s why I jumped at the chance to be part of this conversation.

Sonnenfeld: I agree with what Jacob said. Taking positions that are risky and pushing into new frontiers, whether it’s in intellectual domains or public discourse, is the only reason that tenure exists. If there’s a reason for it at all, it is in fact to take those chances.

The reason professional schools exist, and academic disciplines, like Jacob’s, that reach from pure scholarship to the applied world of everyday policy, is that it’s important that this work not stay locked away in databases and libraries, that it be applied to the world around us. If I see something where it’s a topic I know something about, I will take the opportunity to intervene.

I’ve been talking with both the candidates and campaign managers of several on the Republican side and expect to again on the Democratic side, as I have also done for many years. Never as a paid advisor but rather to share academic insights along the lines of what Jacob referred to earlier when he has given advice to campaigns as this “appropriate role for scholars to play when their research speaks to important public problems.” My intent is to help every candidate, whatever their positions are, to make the best possible case for what they want, rather than to attack each other in ad hominem attacks—which I think is a lose-lose for the country and for them.

Q: You have also commented publicly on candidates’ leadership histories and approaches.

Sonnenfeld: They should be accountable for their past, and if I see gross misstatements and mischaracterizations, I think it’s important that there be some institutional memory, some public awareness of what the actual facts are. Let people judge based on the facts.

Interview conducted and edited by Jonathan T. F. Weisberg.